World Press on Age of the Warlord in Afghanistan, Post-Lukashenka Belarus: New Age Islam's Selection, 7 October 2020

By New Age Islam Edit Bureau

7 October 2020

•

The Age of the Warlord Is Coming to an End in Afghanistan

By

Johnathan Krause

•

Post-Lukashenka Belarus: Close Ties to Moscow but Improved Relationship With the

West?

By Grigory Ioffe

•

China Turning Russia’s Taiga Into a Desert, Enriching Moscow but Outraging

Siberians

By

Paul Goble

•

Can Turmoil in Belarus and Karabakh Inspire a New Patriotic Surge in Russia?

By

Kseniya Kirillova

-----

The

Age of the Warlord Is Coming to an End in Afghanistan

By Johnathan Krause

October 2, 2018

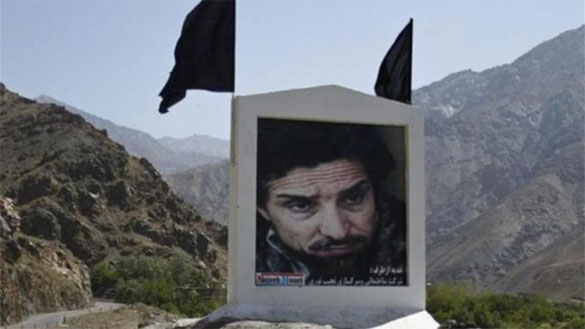

Memorial of warlord Ahmad

Shah Masood (Source: al-Jazeera)

----

The age of warlords in Afghanistan may

finally be ending. The beginning of the end started before Afghanistan

attracted the world’s attention on September 11, 2001: thus, September 9, 2018,

marked the death, 17 years ago, of Ahmad Shah Masoud, a Tajik commander who was

assassinated by members of al-Qaeda posing as journalists (Tolo News, September

9, 2018). And as a bookend of sorts for this period, Jalaluddin Haqqani,

another commander, died earlier last month, on September 3, 2018.

Both men were important figures in the war

against the Soviet Union in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Haqqani rose to

prominence as a beneficiary of support from the United States’ Central

Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Saudi government, and Pakistan’s Inter-Services

Intelligence (ISI) (Afghanistan Online, September 18, 2008). Whereas, Massoud

repeatedly thwarted Soviet plans to invade the Panjshir Valley, north of Kabul

(Afghanistan Online, November 18, 2007).

Although the two men were affiliated with

national groups like the Northern Alliance and the Taliban, respectively, they

were also quasi-independent warlords with their own following. During the

Soviet occupation and subsequent Afghan Civil War in the 1990s, Massoud built

up a personal army of fighters loyal to him (Afghanistan Analyst Network, May

30, 2014). Haqqani similarly built up his own network. In 1996, the latter man

became an ally of the Taliban and provided this militant group with an

important base in southeastern Afghanistan, where few of its members had connections

(Afghan Analysis Network, September 20, 2012).

The two men’s deaths are representative of

a long-term shift occurring in Afghanistan: throughout the country, warlords

are becoming obsolete. Over the past two years, the Afghan government has acted

against them, including the dismissal and forced exile of important northern

commanders. General Abdul Rashid Dostum left Afghanistan for Turkey last year,

after allegations of kidnapping and assault on a political rival (Tolo News,

August 13, 2018). The Afghan Attorney

General’s Office filed charges against him in court for the offense (Tolo News,

July 28, 2017). And Atta Mohammad Noor, dubbed the “King of the North” for

ruling Balkh Province as governor for 14 years, reached an agreement with the

Afghan government to step down (Gandhara, March 21, 2018). President Ashraf

Ghani ordered Noor to vacate the governor’s office in December 2017, but Noor

initially refused to leave his power base (Tolo News, March 21). Abdul Karim

Khudam, a Noor ally and member of a powerful political party, likewise refused

to step down after being sacked by Ghani (Tolo News, February 19).

Nevertheless, he eventually resigned days later after an agreement between his

political party (Jamiat), and the national government (Tolo News, February 20).

It is noteworthy that two northern governors were dismissed within months of

each other.

The country’s remaining warlords are also

losing their grip on power due to factionalism and their inability to control

it. Although General Dostum returned to Afghanistan recently this year, he has

lost control of his own political party. Dissidents from his faction, Jombesh,

formed their own political grouping, New Jombesh, last year (Afghanistan

Analysis Network, July 19, 2017). This formation is significant because Dostum

had previously reacted violently to dissent within Jombesh. In one instance,

his militia kidnapped and tortured another political rival who was preparing to

mount a challenge to Dostum’s leadership within the party (Afghanistan Analysis

Network, July 19, 2017). The only reaction to the break between old and new

Jombesh has been public scorn from the former against the latter. Dostum

supporters and “old” Jombesh members called the new party “Agents of the

Palace” and accused them of being “affiliated with the government” (Afghanistan

Analysis Network, July 19, 2017).

Independent agencies in Afghanistan have

also contributed to the demise of the warlords by taking away an important

source of their power—national office. Afghan warlords were once considered

among the country’s most influential elites, having gained access to government

facilities and jobs in the bureaucracies (Asia Times, May 14, 2018).

Nonetheless, the Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan (IECC) recently

announced that warlords will not be allowed to stand for elections (Tolo News,

July 26). Already 25 candidates with links to non-governmental armed groups

were removed from the list of parliamentary candidates (Tolo News, August 4).

Lastly, international organizations and

European states have stepped up calls for justice against Afghanistan’s warlord

class. In mid-August, the ambassadors for the European Union and Norway in

Kabul said, in a joint conference, that the case against Dostum (for the

assault on a political rival mentioned above) should be concluded via legal

channels since he returned to Afghanistan (Tolo News, August 13). They added

that “nobody should be above the law” and it is important that all Afghans work

together peace, stability, and democracy throughout the country, based on full

respect for the rule of law of all citizens (Tolo News, August 4, 2018).

The above actions are a dramatic turnaround

in the government’s previous policy toward the warlords. Heretofore, the Afghan

state utilized indigenous warlords as powerful allies against the Islamist

insurgency. Thomas Rutting, a co-director of the Afghan Analysts Network, noted

that private militias and strong men have flourished in modern Afghanistan

because of their usefulness in the war against the Taliban (Afghan Analysts

Network, March 20, 2015). Warlords were given money, governorships, cabinet

positions, and even vice presidencies. In addition, they were afforded access

to government facilities and jobs, as mentioned above.

The decline of warlordism is helping to

strengthen state sovereignty and boosting President Ghani’s domestic authority.

Last year, he pledged that his people will celebrate the sovereignty of law.

The law is not sovereign when certain officials consider themselves untouchable

or beholden only to the power of the gun, Ghani pointed out (Tolo News, March

15, 2017). The removal of Dostum, Noor and Khadim thus offers him an

opportunity to appoint new loyal government officials who will contribute to

consolidating Kabul’s control over the wider country. Now, there are fewer

strongmen with militias and guns to prevent the writ of the government,

especially in former warlord-held areas.

The end of the warlords will almost

certainly impact the civilian population the most, promising to dramatically

increase overall security. The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan

(UNAMA) noted, in its 2014 “Annual Report on the Protection of Civilians in

Armed Conflict,” that there was a 194 percent increase in civilian deaths

caused by warlord militia groups from the previous year (Afghan News Network,

March 4, 2015). Most of those casualties were caused by fighting between rival

pro-government militias (Afghan News Network, March 4, 2015). The UNAMA also

noted the “impunity enjoyed by pro-government armed groups, which permitted

them to commit criminal acts including assault, intimidation, and lack of

protection for civilians and communities” (Afghan News Network, March 4,

2015).”

With the Ghani administration determined to

remove warlords from power and the IECC’s use of legal tools to prevent them

from gaining power at the national level, the chapter on Afghanistan’s warlords

seems to be closing. Once powerful actors, they are increasingly being held

accountable for their actions and can no longer wholly ignore the writ of the

government or the chorus for justice by the international community. The recent

twin deaths of Ahmad Shah Masoud and Jalaluddin Haqqani may thus come to

symbolize the end of an era.

https://jamestown.org/the-age-of-the-warlord-is-coming-to-an-end-in-afghanistan/

----

Post-Lukashenka

Belarus: Close Ties to Moscow but Improved Relationship with the West?

By Grigory

Ioffe

October 6, 2020

(Source: Reuters)

----

Arriving at some clarity regarding the

situation in Belarus has become harder than ever before. An unstable

equilibrium begets a cacophony of opinions that do not lend themselves to

generalization or to teasing out a common idea. Alexander Klaskovsky of Belapan

writes, “[Presidents Alyaksandr] Lukashenka [of Belarus] and [Vladimir] Putin

[of Russia] are sitting in the same anti-Western trench” (Naviny, September

29). Arseny Sivitsky of the Minsk-based Center for Strategic Studies argues,

“[French President] Emmanuel Macron’s statement that Lukashenka has to go and

Macron’s meeting with [Lukashenka’s chief rival in the August presidential

elections] Svetlana Tikhanovskaya in Vilnius not only derive from Minsk’s

reluctance to communicate with the West but also constitute a position Macron

reconciled during his phone talk with Vladimir Putin; this position reflects

attitudes in the Kremlin” (Forstrategy, September 29). Finally, in an interview

with Current Time TV, Arkady Dubnov, a liberal Moscow-based political analyst,

posited, “Moscow may turn out to be late installing its creature that would

replace Lukashenka, and in that case, it would have to negotiate with

Tikhanovskaya, too” (Current Time, September 28).

What

nobody calls into question is that the Belarusian political regime has survived

the street protests and, despite a few widely publicized acts of disobedience,

the entire power vertical, especially law enforcement, retained the appearance

of a monolith. It is also becoming exceedingly clear that although the social

base of the protest movement may be fairly wide, President Lukashenka’s base of

support is not that narrow either and extends beyond the habitual formula of

“country and small-town folks, retirees and the less educated.”

Opinions about Lukashenka’s legitimacy vary.

As Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmitry Kuleba put it, “Lukashenka does not have

legitimacy anymore, but the opposition does not enjoy enough of it yet”

(Tut.by, September 30). However, according to philosopher Viacheslav Bobrovich

of Belarusian State University, if Lukashenka has lost legitimacy in the eyes

of a critical mass of the Belarusian public, it is only in a narrowly defined

political sense. His administration remains orderly and performs its functions

vital for everyday life reasonably well, and it is not awash in corruption (Facebook.com/vbobrovich,

September 26). Kirill Koktysh, a Minsk-born professor at Russia’s MGiMO

University, observes that Belarus witnessed the third recent failed color

revolution, following those in Venezuela and Hong Kong (Author’s interview,

October 2).

Arguably, a tentative consensus has developed

suggesting that the “unstable equilibrium” in Belarus is not so much because of

continuing protests but due to the uncertain actions of the Kremlin. Actors on

all sides of the Belarusian political divide seem to stress the necessity of

reaching out to Russia. “We do have contacts with Moscow,” acknowledged Pavel

Latushko, one of the exiled leaders of the protest movement, in an interview

with Radio Liberty (Svaboda.org, September 29). Against this backdrop, the

European Union’s sanctions imposed on Minsk do not elicit a serious reaction.

About 40 Belarusian officials and security service authorities—but not

Lukashenka himself—are now personae non gratae in the EU (BBC News—Russian

service, October 1). The reputable Minsk-based analyst Artyom Shraibman

describes Western sanctions as pro forma a demonstration of Europe’s

self-respect but thoroughly impotent in terms of exerting any influence. Yet he

suggests that a miniature Marshall Plan for Belarus could eventually begin to

matter in the eyes of the Belarusian nomenklatura, if Moscow does not depose

Lukashenka but the economy sharply declines (T.me/shraibman, October 2).

In

contrast to the EU sanctions, Minsk’s responses prove more important, as these

actions will further reduce Belarus’s exposure to Western influence. For

example, Minsk demanded that the Lithuanian embassy to Belarus reduce its

personnel from 25 to 14 diplomats and the Polish embassy from 50 to 18. The

Belarusian government claims this order was prompted by “destructive activity”

carried out by these countries inside Belarus (Svaboda.org, October 2). Since

the Baltic States’ travel sanctions on Belarus target many more people than the

EU’s and include Lukashenka, Belarus announced symmetrical restrictions

(Tut.by, September 29). On October 2, Minsk annulled the accreditation of all

foreign media correspondents. Reaccreditation commenced three days later,

prioritizing journalists who are citizens of the countries that their

respective media outlets represent. This strategy may let down quite a few

Belarusian citizens representing these foreign media outlets (Svaboda.org,

October 2).

Concerning the Vilnius meeting between Macron

and Tikhanovskaya, the Belarusian foreign ministry caustically called the

exiled opposition leader an “attraction” in the Lithuanian capital that foreign

visitors are now mandated to visit (BelTA, September 29). Whereas Lukashenka,

as a “politician with experience,” issued advice to the “immature” Macron to

stay away from Belarus and preoccupy himself with his own country’s problems.

The Belarusian leader even crudely counseled his French counterpart against

paying too much attention to the former presidential candidate in Vilnius lest

Macron wind up with personal problems simply because that candidate, Ms.

Tikhanovskaya, happens to be a woman (Tut.by, September 29).

Multiple publications have declared the

ultimate failure of Belarus’s multi-vector foreign policy; some have

fatalistically entertained the idea of shutting down the Ministry of Foreign

Affairs, which would hardly be needed if Minsk is not allowed to maintain

relations with any foreign powers besides Moscow (Naviny, September 22). Andrei

Savinykh, a former diplomat who chairs the Foreign Affairs Commission of Belarus’s

House of Representative (lower chamber of parliament), has been particularly

vocal in repudiating Minsk’s multi-vectoralism: in the current geopolitical

situation, the West has demonstrated its irrelevance and hostility toward

Belarus, whereas Russia embodies all hope (BelTA, September 29).

Clearly, however, not all inside Belarus or in

the West agree. Thus, in their article aimed at the Western audience, Yauheni

Preiherman of the Minsk Dialogue Council and Thomas Graham of the United States

Council on Foreign Relations, suggest that contacts with Minsk should be

retained at all costs and a US ambassador should quickly be sent to Minsk.

After all, talking about Belarus only with Moscow over Minsk’s head will show

Belarusian society that it does not matter in the eyes of the West. “A

post-Lukashenko Belarus, with close ties to Moscow but an improved relationship

with the West, remains a possible medium-term outcome of the current crisis. It

might not be the one many in the West had hoped for, but it is still a good

alternative and perhaps the best option in the current climate. Well-crafted

policy could make it a reality,” the two analysts conclude (Foreign Affairs,

October 2).

https://jamestown.org/program/post-lukashenka-belarus-close-ties-to-moscow-but-improved-relationship-with-the-west/

-----

China

Turning Russia’s Taiga into a Desert, Enriching Moscow but Outraging Siberians

By Paul Goble

October 6, 2020

Logging in Siberia (Source:

RT)

-----

Since Vladimir Putin became president,

Russia’s forests have declined in size by 45 million hectares, some 6 percent

of the country’s total. The shrinking forest cover has been the result of the

spread of uncontrolled forest fires (80 percent) as well as increased

harvesting (20 percent), much of that for export. That distinction between

losses from fires and regular cutting, however, is less sharp than one might

expect: many Russians allege that some of the fires, especially in Siberia and

the Russian Far East, were set deliberately to conceal illegal cutting

(Newizv.ru, September 9). True or not, the issue is becoming ever more

political for two reasons. First, a large part of the new logging operations

are being carried out by Chinese firms or Russian subcontractors working for

them. And second, the profits from exports of wood (processed and unprocessed)

to China are going almost exclusively to oligarchs in Moscow rather than to

people in the regions that are being left without forests and more at risk of

fires and flooding than ever before.

The

main drivers of this development, Russian experts say, lie in the new legal

code governing forests, the Putin government’s commitment to supply China with

lumber both to earn money and to cement ties between the two Eurasian giants,

as well as the fact that in the most-affected regions, the governors are not

local people but appointed outsiders. Those Kremlin-imposed non-local governors

tend to show less concern for putting the interests of their federal subjects

first (Rusmonitor.com, October 2).

Both

Soviet legislation and Russian laws adopted in the 1990s provided significant

protection to Russian forests. But the forestry code adopted under Putin’s

tenure eliminated most restrictions on the use of forests, shut down fire-watch

and fire-fighting centers, and handed over large segments of the country’s

seemingly endless forests to businessmen, whose only interest has been to

profit from them even if stripping the timber increased the chronic risk of

catastrophic fires and floods. The Kremlin took these steps to ensure that it

would continue to enrich itself and its private-sector allies as well as to

please Beijing, which looks north to Siberia and the Russian Far East for wood

and pulp. China is currently responsible for logging and exporting 90 percent

of all timber products from those regions for its own needs. This conversion of

areas forested from time immemorial into what some call “lunar landscapes” is

becoming a political issue, with local politicians demanding a return of local

control over the use of forest, while Moscow plays defense.

One

Russian commentator, Vladimir Vorsobin, says that this has sparked “a small

civil war” between those engaged in logging and profiting from it and the

surrounding populations (Komsomolskaya Pravda, October 2). Some of the

protesters in Khabarovsk, in the Russian Far East (see EDM, August 3, 4), have

raised this issue. But the most dramatic engagement in this “war” came last

week (October 2), when Vorsobin published an open letter to President Putin

summing up the anger of Russians living along the Russian-Chinese border and

demanding that he change course. In fact, the commentator writes, Russians are

outraged that Putin has promised to limit Chinese exploitation of Russian

forests repeatedly but, in fact, has continued to profit from the sale of

timber to Beijing. From their point of view, he continues, Russians now believe

Putin is selling out the interests of the people of Siberia and the Russian Far

East for profit, a view that combines class and regional anger at Moscow and is

becoming the foundation for a serious political challenge to the center.

At a

meeting in early October, Putin promised that he would take steps to regulate

the situation, especially after officials said that much of the money from

sales to China is going into the coffers not of the central government but into

shadowy illegal firms. Opponents of the current approach to forest management

were hopeful when business people were excluded from the meeting; but they were

troubled by Putin’s failure to take a tough line and even more by the

subsequent absence on the Kremlin website of any details regarding what might

be done. Some observers have concluded that nothing serious is likely to

happen—banning the export of raw lumber, the main announcement Putin did make,

will mean that the Chinese will simply process the felled wood in Russia and

use its own workers to do so, further outraging local Russian residents.

Instead, the Russian taiga will continue to disappear into Chinese hands, and

any profit from it will flow out of the local regions (Newizv.ru, October 2).

The

conflict over this issue between the central government and business on the one

side and the people on the other has not been limited to blog posts, however.

Some activists in the Russian Far East have set fire to lumber already

harvested and set to be exported to China. “Local bloggers,” one Russian

commentator, Aleksandr Nemets, says, “are calling this a partisan war” against

both Beijing and Moscow, which supports the Chinese enterprises. Activists have

organized large protest gatherings, including in Khabarovsk, whereas Moscow has

removed regional officials, including the Communist governor in Irkutsk, who

tried to block the export of wood to China (Kasparov.ru, January 9).

According to Nemets, who resides in the United

States though closely tracks developments in Asiatic Russia, he does not know

how things will develop in the Russian Far East. China remains in a very strong

position and has Moscow’s backing. “But obviously, the southeastern regions [of

the Russian Far East] have already passed the point of no return,” he concludes

(Kasparov.ru, January 9). If this assertion proves true, the Kremlin will

eventually face much bigger problems east of the Urals than fires, floods and

critical internet posts.

https://jamestown.org/program/china-turning-russias-taiga-into-a-desert-enriching-moscow-but-outraging-siberians/

-----

Can

Turmoil In Belarus And Karabakh Inspire A New Patriotic Surge In Russia?

By Kseniya Kirillova

October 6, 2020

(Source: Kremlin.ru)

----

Protests in Belarus and the fighting in

Karabakh have upended relations between the Russian authorities and the leaders

of Minsk and Yerevan. In the past, Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka

and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, despite generally acting in

conjunction with Moscow, have nonetheless tried to distance themselves from

Russia as much as possible and periodically sided with the West in condemning

certain Kremlin actions (Ukrinform, September 7, 2018). However, in recent

months, each of them, for his own reasons, has had to turn to Russia for help.

Lukashenka, rejected by what appears to be a majority of his own people and not

recognized by the West as the legitimate president (Eeas.europa.eu, September

15), began to seek Vladimir Putin’s support. He has sought to affirm his

absolute loyalty to the Kremlin and prove Belarus’s irreplaceable role in

protecting Russia “from Western aggression” (YouTube, September 9). Similarly,

Pashinyan, in seeking Moscow’s support in Armenia’s war against Turkish-backed

Azerbaijan, also promised his loyalty (Gazeta.ru, September 30).

All

this encouraged the Russian authorities in recent weeks to launch a new round

of pro-imperialistic propaganda. Using the statements of the leaders of Belarus

and Armenia, the media began to promote the idea that only Russia can help its

neighbors, which automatically demonstrates the Russian Federation’s status as

a great power (Svobodnaya Pressa, September 30). At the same time, Russian

propaganda emphasizes that the only way for the post-Soviet states to survive

is to abandon their “multi-vector” approaches and fulfill a number of

conditions set by the Kremlin, including recognizing Crimea as part of Russia,

integrating more deeply with the Eurasian Economic Union, lobbying for the

lifting of anti-Russian sanctions, reducing the United States’ influence and

banning a number of pro-Western non-governmental organizations (NGO), and so on

(T.me/russica2, September 28). The general editor of RT, Margarita Simonyan,

notably stated, “Armenia is either doomed to return to Russia or simply doomed”

(Twitter, September 28). Various Russian observers argue that Armenia cannot

survive without becoming part of Russia.

Nevertheless, independent economists and

sociologists are inclined to believe that, unlike in 2014, the Russian

authorities will not succeed in sparking a new “patriotic surge” within Russian

society based on neo-imperial ideas. Economist and the director of the Center

for Post-Industrial Society Studies, Vladislav Inozemtsev, believes the

military conflict in Karabakh is worrisome for representatives of the Armenian

and Azerbaijani diasporas in Russia, but not for ordinary Russians. “In

addition, people understand quite well that the leaders of neighboring

countries only turn to Russia for financial support, and nothing more,” he said

(Author’s interview, September 29).

Elena Galkina, a political analyst and

doctor of historical sciences, agrees. “Imperial propaganda is accompanied by

another devaluation of the ruble and, accordingly, a rise in prices, which

today worries Russians much more than foreign policy influence. As for Belarus,

ordinary Russians will rather regret that Belarusian sausage and milk will

disappear in stores, which will certainly happen if Belarus is absorbed by

Russia,” the expert suggests (Author’s interview, September 29).

These analysts’ conclusions are supported

by sociological data. Based on the results of an August poll, the deputy

director of the Levada Center, Denis Volkov, noted that although the majority

of Russians support the further development of economic cooperation between

Moscow and Minsk, the desire to “annex Belarus” and “include it in Russia” is

marginal—only a small number of elderly respondents express support for such

unification (Forbes.ru, September 6).

The continuing decline in economic

well-being also does not contribute to the readiness of Russians to make new

sacrifices for the sake of the “greatness of the empire.” According to the

state pollster Rosstat, every fourth child in Russia lives below the poverty

line (Deutsche Welle—Russian service, August 7). Experts argue that the

government is unable to solve the problem of declining incomes; by the end of

2020, 16 percent of the working-age population may live below the poverty line

(Gazeta.ru, June 3). Such a situation does not lead to an increase in

patriotism but, on the contrary, to a feeling of dissatisfaction with life and

distrust of the authorities (see EDM, July 8).

For now at least, the Belarusian street

demonstrations against Lukashenka are incapable of inspiring Russians to

increase their own protest activities. “Russian media are sending contradictory

signals to the domestic audience, hinting that the situation [in Minsk] is

under control. Only if a successful political revolution really takes place in

Belarus, will it be able to influence Russians,” Galkina believes. “Many

[ordinary Russians] stand in solidarity with the Belarusian opposition, but

they hardly think about replicating its experience,” Inozemtsev clarified

(Author’s interview, September 29).

At

the same time, Russian sociologists note that the country’s liberal opposition

is extremely divided and does not have a clear program of economic reforms or

understanding of issues of state structure. According to Sergei Belanovsky and

Anastasia Nikolskaya, the prevailing feeling among the opposition manifests

itself in “an atmosphere of expectation of a social miracle that will

supposedly come true when the existing regime is replaced by a democratic one.”

The two experts contended that “there is a gap between the real programs of state

and economic reforms and ideas about these reforms among the democratic

opposition.” And yet the supporters of liberal reforms, despite their lack of

professional knowledge, are not ready to cooperate with “latent dissidents”

among the lower and middle-level professional officials (Riddle, September 6).

Belanovsky and Nikolskaya fear the Russian

opposition may fragment if an opportunity to democratically transform the

country suddenly presents itself. This breakup could, in turn, lead to a stream

of insoluble political conflicts that will again revive a desire within Russian

society to “return to the idea of a ‘strong hand’ that will restore order”

(Riddle, September 6). However, even in such a case, the Russian people only

appear inclined to support authoritarianism as the “lesser evil” compared to

anarchy—not as a result of imperial nostalgia and a desire to “save”

neighboring countries.

https://jamestown.org/program/can-turmoil-in-belarus-and-karabakh-inspire-a-new-patriotic-surge-in-russia/

----

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African

Muslim News, Arab

World News, South

Asia News, Indian

Muslim News, World

Muslim News, Women

in Islam, Islamic

Feminism, Arab

Women, Women

In Arab, Islamophobia

in America, Muslim

Women in West, Islam

Women and Feminism