Husain Madani’s Inclusive and Democratic Brand of Islam Gaining Traction amid Debate over Taliban-Deoband Link

By

Kaniz Fatma, New Age Islam

2 October

2021

Examining

Dissimilarities between Taliban and Deoband Links in India

Main

Points:

1. Taliban are

diametrically opposed to The Model of Their Greatest Sheikh Husain Madani.

2. Husain

Madani advocated composite nationalism—a united India for Muslims and

non-Muslims.

3. Madani holds

that the basic spirit of the Quran is to promote peaceful coexistence in a

multi-cultural, multi-racial, and multi-religious society.

4. Though the

Taliban Admire Husain Madani, they reject his inclusive and democratised brand

of Islam.

5. Taliban are

unlikely to follow Madani’s model, but if they do not change their ways, they

will face considerable challenges.

6. Indian

Deobandi defender is advising the Taliban to revert to their most revered

Sheikh's teachings and reject fanaticism in favour of moderation and inclusion.

......

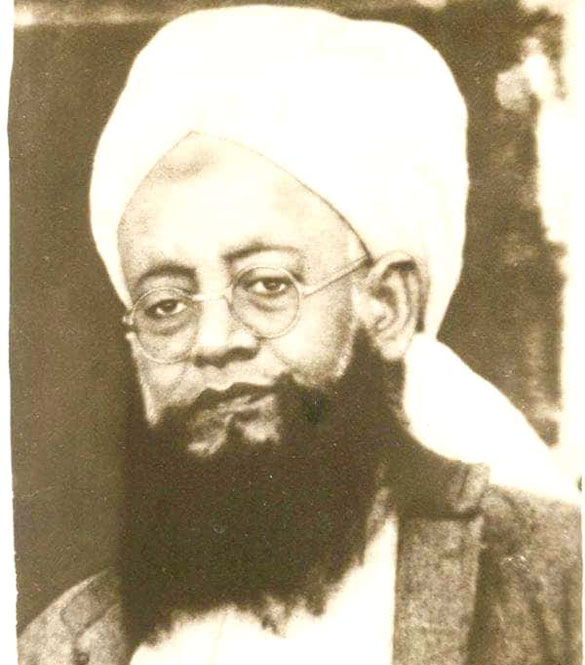

Husain Madani Deobandi

----

Since the

Taliban assumed control of Afghanistan, there have been disputes about

Deoband's relationship with the Taliban and their religious doctrine and ideas.

Different people speak in a variety of ways. The Taliban's affiliation with

Deoband is also being discussed in newspapers and electronic media. On what

basis do the Taliban regard Husain Ahmed Madani Deobandi as their leader? This

is a crucial question that must be answered in order to comprehend the

Taliban-Deoband connection. When you examine Husain Madani’s ideology, you will

notice that it is diametrically opposed to that of the current Taliban. Some

even propose that the Taliban could learn from their greatest Sheikh, Husain

Ahmad Madani Deobandi who is known for advocating composite nationalism—a

united India for Muslims and non-Muslims. What's the back-story to all of this?

Let's have a look at it in this article.

In answer

to a media question on the current situation in Afghanistan, the President of

Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind, Maulana Syed Arshad Madani, remarked recently in a lengthy

interview that some people are associating the Taliban with Deoband and Darul

Uloom, which he does not believe is correct. Arshad Madani claims that his

India-based seminary, Darul Ulum Deoband, has no present ties to the Taliban

because none of the Taliban’s commanders was educated there. He claims,

however, that the Taliban have historical roots in the Deoband Movement, whose

anti-British leaders founded an exiled Indian government in the second decade

of the twentieth century. The purpose of the Taliban was to free their homeland

from the British through an armed struggle in cooperation with the Ottoman

Empire, the Durrani Amir, and Pashtun tribes spanning the British

India-Afghanistan border.

Arshad

Madani’s father, Maulana Syed Husain Ahmad Madani was imprisoned along with his

teacher and prominent Deobandi cleric Maulana Mehmud Hasan, in Malta after the

conspiracy was discovered by the British in 1916. Later, Husain Madani joined

Gandhi and opposed the establishment of Pakistan as a homeland for Muslims in

South Asia, stating that nation-states could not be created solely on religious

grounds. “Today’s Deobandis are the offspring or grandchildren of those who

were connected with that movement and their exiled government there,” said

Arshad Madani.

During the

same interview, Maulana Arshad Madani stated that “we have no soft corner for

the Taliban and we have no opinion about anyone” and that “the future will tell

us what the Taliban’s and their country’s system is. How they are going to

implement Islamic law in their country will be known.” He also stated that the

essential foundation for the long-term viability of any government is the

establishment of national unity and fraternity, the creation of equality among

citizens, the elimination of discrimination between the minority and the

majority, and the prevention of sectarian animosity.

“We would

welcome the Taliban if they created a norm for minorities and majorities,

providing them with economic, educational, and other civil rights, as well as

ensuring peace and order in the country and the lives of all citizens. We will

praise and proclaim that this revolution is an Islamic revolution if they grant

equal rights to all citizens; if they do not follow this manner, there will be

opposition around the world and we too will oppose them”, said Arshad Madani.

In the

midst of the current controversy over the Taliban-Deoband relationship, I

recently read an article titled “Can the Taliban Learn from Their Greatest Sheikh?”

According to Ammar Anwer’s article, the Taliban regard Husain Madani as their

greatest Sheikh. Husain Madani, on the other side, is portrayed in the article

as a moderate, peace-loving man who promoted Hindu-Muslim friendship and

reconciliation.

The article

proves that there is a mismatch between the current Taliban’s ideology and

Husain Madani’s ideology by portraying the moderate face of Husain Madani. The

article appears to have called on the Taliban regime to accept Husain Madani's

moderate beliefs and ideologies and renounce their extremism and bigotry. The

following are a few summarised highlights from the article.

According

to the article, Husain Madani’s political action began with his participation

in the Indian nationalism struggle. He was a founding member of “the Gandhian

non-cooperation movement”, wearing the “hand-loomed cloth popularised by Gandhi

as a symbol of resistance”. He was arrested at least once every decade from

1916 till India's independence in 1947.

Despite

being a religious traditionalist, Husain Madani had a unique political

imagination. As Indian independence drew near, Madani vehemently opposed

Muslims who advocated for a separate nation for Muslims. Instead, he contended

that Muslims may live as devout Muslims in “a religiously plural society as

full citizens of an independent, secular India”.

According

to the article, Madani dismissed the idea of constructing a polity on Islamic

principles as impracticable. His singularity stems from his status as a

political activist as well as a prominent Islamic scholar who was able to

contextualise his support for modern territorial nationalism within Islamic

traditions. His support for territorial nationhood brought him into conflict

with other Islamic thinkers of the time, most notably Dr Mohammad Iqbal, the

poet and philosopher who was the chief ideologue of Muslim territorial autonomy

in the Subcontinent, and Syed Abul Ala Maududi, the then-emerging Islamist

scholar.

Husain

Madani, as we all know, penned Muttahida Qaumiyat Aur Islam (Composite

Nationalism and Islam) in 1938, advocating composite nationalism—a united India

for Muslims and non-Muslims. In the book which opposed India’s partition,

Madani pushed for the concept of a “composite nationalism” within a united

India, which he considered would be more favourable to the development and

prosperity of his people over the entire subcontinent than any religious split.

Madani stated in this book that a “Qaum” (nation) in the Prophet's

terminology could be made up of believers and nonbelievers working together for

a similar goal and that this would be the model for India’s “Qaum”

(nation).

Citing some

references from the book, Mr Ammar states that Husain Madani persuaded his

audience to support a multi-religious India by citing texts from the Qur'an and

demonstrating that the prophets shared the same territory with those who

rejected their message, but that this did not make them two separate nations.

Madani claims that the basic spirit of the Quran is to promote peaceful

coexistence in a multi-cultural, multi-racial, and multi-religious society. He

mentioned the charter of Medina, which was established by the Prophet Mohammad

(peace be upon him) upon his arrival in Medina, and in which he merged Muslims,

Jews, and Christians into a single nation. According to Madani, the Prophet of

Islam drafted a constitution that brought people of many faiths together as one

nation, declaring them to be one community ("Ummah") apart from those

outside the city.

According

to the citations in the article, Maududi disputed Madani’s doctrine of the

Median Charter, claiming that non-Muslims can only be treated as

"dhimmis" (protected citizens) in an Islamic state if they accept to

pay the annual protection tax known as "Jizya." Maududi also viewed

the entire concept of contemporary territorial nation-states to be alien to

Islam, and secularism to be the first step toward atheism. In response to

Maududi’s criticism, Madani stated that such a notion leads nowhere. “Falsafiyyat

(philosophy) does not settle Siyasiyyat (politics),” he added. The

anti-colonial and constitutional movement was the reality of the day for Madani.

The attempt of Maududi to propose "an Islamic order" was “both

abstract and unrealistic”. He went on to say that, given the lack of religious

unity among Muslims, what would the Islamic government entail? He listed the

various sects and orientations within Islam, noting that each “considers his

argument beyond that of Plato or Socrates.”

The article

goes on to suggest that Madani's opposition to Islamist politics was not solely

motivated by the fact that Muslims were a minority in India, making Islamic

governance impractical through democratic methods. In fact, he argued that even

in a largely Muslim state, there could be no unanimity on the specific

character of Islamic authority and that such action would inevitably exacerbate

religious tensions.

Madani,

according to the reports cited in the article, was also opposed to the idea

that Islamic “laws” existed in the sense of absolute universals that applied to

all times and places. Maududi must be living in a “fanciful world,” he claimed,

where he can simply ignore "the truths of India's mixed and heterogeneous

population.” “How could he imagine putting into practise the regulations he

drew from theoretical premises, such as the criminal sanctions (stoning,

prohibition, or monetary restitution for murder) that any ruler professing to

be governed by Islamic law would enact?” Such regulations are neither suitable

nor ethically obligatory in a society like India, Madani concluded.

When the

subcontinent was divided into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan

in August 1947, Madani’s gallant efforts to prevent India's separation on

religious grounds were eventually failed. Madani urged Deobandi scholars who

had moved to Pakistan to remain loyal to their new home and wished for peaceful

coexistence between the two countries.

The article

holds that, unfortunately, Deoband scholars in Pakistan began campaigning for

Islamisation very early on and actively participated in the Afghan Jihad

against Soviet occupation in the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, their viewpoint

diverged significantly from that of the Indian Deoband, which continues to

strongly favour a secular structure. According to some academics, Pakistani

Deobandis became significantly infused with Wahhabism under the sponsorship of

the Pakistani military and Saudi Riyals, straying from the Classical Islam that

the Indian Deoband still adheres to.

According

to Mr Ammar, after the Iranian revolution in 1979, Saudi Arabia was concerned

that a Shia country — Iran — would come to rule the Muslim world. As a result,

they began sponsoring seminaries around the Muslim world including Pakistan for

promoting Wahhabi-style Islam. He stated that Wahhabi influence grew steadily

in Pakistan and Afghanistan during the 1980s when the CIA and Saudi Arabia both

provided supplies to Mujahideen guerrilla groups fighting the Soviet occupation

of Afghanistan during the Cold War. As a result, Deobandi Islam progressively

absorbed Wahhabi culture. “The Afghan Taliban also follows the Deobandi Islam,

and most of its leadership consists of graduates from Deobandi seminaries,

including in particular the famous (or infamous) seminary Dar al-Ulum Haqqania,

which is based in the town of Akora Khattak, in Northwestern Pakistan”, he

wrote.

Mr Ammar,

defending Indian Deoband, claims that the Taliban, like the majority of their

Pakistani allies, reject Husain Madani’s inclusive and democratised brand of

Islam. True, the Taliban still admire him, but their acts contradict the

message Madani worked so hard to spread. Although it seems unlikely that the

Taliban will follow Madani’s model, it is also true that if they do not change

their ways, they will face considerable challenges in acquiring Western

legitimacy, which might lead to a severe economic crisis in the country.

Mr Ammar

believes that because the Afghan public has been forced to unceasing conflict

for more than four decades and yearns for stability and internal religious and

ethnic unity, the Taliban should follow Husain Madani’s model proposed in the

1930s, which is both Islamic and modern. He rightfully concludes by advising

the Taliban to revert to their most revered Sheikh's teachings and honestly

demonstrate that they have evolved and rejected fanaticism in favour of

moderation and inclusion.

Referenced

Article: https://tribune.com.pk/article/97485/can-the-afghan-taliban-learn-from-their-greatest-sheikh

URL: https://www.newageislam.com/radical-islamism-jihad/husain-madani-taliban-afghanistan-/d/125493

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism