Blasphemy Laws Have Turned Muslim Countries into Killing Fields

Muslims

and Non-Muslims Alike Can Be Killed For Blasphemy in Pakistan

Main

Points:

·

In Pakistan 1500 people are being prosecuted

under blasphemy laws.

·

70 people have been killed since 1990 extra

judicially for alleged blasphemy.

·

Quran does not prescribe any physical sentence

for blasphemy.

·

Apostasy is also included in blasphemy.

·

Blasphemy is a political tool to suppress

dissent in Muslim countries.

-----

New

Age Islam Staff Writer

12 October

2021

Blasphemy

or sacrilegious speech or writing is widely debated in the academic circles of

Islam. Many Islamic scholars are of the view that blasphemy is not a crime but

a grave sin against God and His prophet pbuh and so it cannot be punished by

the law, God condemns blasphemy against Himself, His angels and His prophets

(not only Prophet Muhammad pbuh) but the Quran does not prescribe any physical

punishment for blasphemers. Instead, the Quran advises Muslims to practice

restraint and tolerance in face of blasphemy.

But a

section of the Islamic scholars in the 11th century in association with the

power hungry Muslim rulers made blasphemy a criminal offence to be punished by

death. These ulema presented interpretations and explanations of Quranic verses

supporting punishment for blasphemy. For example, Islamic scholar of the 11th

century Imam Ghazali presented the view that those propagating unorthodox views

on God and resurrections should be punished to death as they were influenced by

the Greek philosophy and Shias to corrupt Sunni Islam. After that a number of

Muslim scientists and philosophers were tortured and executed.

This

tradition of considering blasphemy a criminal offense in Islam was taken

forward and even strengthened by some ulema of the 20th century though at the

same time a section of liberal ulema opposed the idea of punishment for

blasphemy on the basis of the verses of the Quran that advise Muslims to

practice restraint and leave the blasphemers only after verbally condemning

them. But the majority of the modern ulema, even the ulema of 21st century,

blasphemy is a criminal offence and should be punished with no less a punishment

than death.

Interestingly,

it has been observed that ulema from Muslim majority countries favour death

sentence for blasphemers and ulema from Muslim minority countries favour only

verbal protest and condemnation. For example, Maulana Wahiduddin Khan, an

Islamic scholar from India held the view that Quran did not prescribe death for

apostasy. Similar view is held by Muhammad Yunus, a scholar of the Quran and

other Islamic scholars of India. But on the contrary, majority of ulema of

Pakistan hold the view that blasphemy should be punished with death.

It is to be

noted that these ulema have included apostasy in the category of blasphemy.

Though the Quran does not prescribe death for apostasy too, the ulema cite the

consensus of majority of ulema for declaring apostasy a kind of blasphemy and

so punishable by death.

Though many

Christian countries have repealed their blasphemy laws or have light

punishment, many Muslim majority countries have blasphemy laws under which

hundreds of Muslims and non-Muslims are prosecuted and killed extra judicially.

In Pakistan

and Iran the blasphemy laws are the strictest. In Pakistan, members of minority

communities --- Hindus, Christians, Ahmadiyyas, Shias and other people

expressing unorthodox views about religion are charged with blasphemy but no

convictions take place. Still the accused are killed by mob or extremists

outside the court. About 70 people have been killed extra judicially after the

cases against them did not stand in the court. This is a very disappointing

situation when the law framed with the approval of the hardline ulema does not

find the accused guilty and still they are killed extra judicially.

In Pakistan

anyone can be charged with blasphemy even if he challenges the behavior of the

clergy. This should change. Liberal thinkers and intellectuals of Pakistan

raise their voice against this tradition but they are always under threat.

Salman Taseer, the Punjab governor was killed by an extremist for demanding a

repeal of the blasphemy laws. The situation seems hopeless as even an Islamic

scholar of the status of Dr Tahir ul Qadri who had published a voluminous fatwa

against suicide bombings and terrorism supports death for blasphemy and holds

the view that even Muslims can be charged with blasphemy.

------

Why Blasphemy Is A Capital Offense

In Some Muslim Countries

By

Ahmet T. Kuru, San Diego State University

(Photo courtesy:

Qantara.de)

----

The Prophet Muhammad never executed anyone for

apostasy, nor encouraged his followers to do so. Nor is criminalising sacrilege

based on Islam’s main sacred text, the Koran. In this essay, Ahmet Kuru exposes

the political motivations for criminalising blasphemy and apostasy

Junaid

Hafeez, a university lecturer in Pakistan, had been imprisoned for six years

when he was sentenced to death in December 2019. The charge: blasphemy,

specifically insulting Prophet Muhammad on Facebook.

Pakistan

has the world’s second strictest blasphemy laws after Iran, according to U.S. Commission on International

Religious Freedom.

Hafeez,

whose death sentence is under appeal, is one of about 1,500 Pakistanis charged

with blasphemy, or sacrilegious speech, over the last three decades. No

executions have taken place.

But since

1990 70 people have been murdered by mobs and vigilantes who accused

them of insulting Islam. Several people who defend the accused have been

killed, too, including one of Hafeez’s lawyers and two high-level politicians who

publicly opposed the death sentence of Asia Bibi, a Christian woman convicted

for verbally insulting Prophet Muhammad. Though Bibi was acquitted in 2019, she fled Pakistan.

Blasphemy

and Apostasy

Of 71

countries that criminalize blasphemy, 32 are majority Muslim. Punishment and

enforcement of these laws varies.

Blasphemy

is punishable by death in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Brunei, Mauritania and Saudi Arabia. Among non-Muslim-majority cases,

the harshest blasphemy laws are in Italy, where the maximum penalty is three

years in prison.

Junaid Hafeez was a lecturer in English

literature at Bahauddin Zakariya University in Multan, Pakistan. Appointed in

2011, he soon found himself targeted by an Islamist student group who objected

to what they considered Hafeez's "liberal" teaching. On 13 March,

2013 Hafeez was arrested – accused of using a fake Facebook profile to insult

the Prophet Muhammad in a closed group called "So-Called Liberals of

Pakistan". Imprisoned without trial for six years, much of that time spent

in solitary confinement, the academic was finally sentenced to death in

December 2019

-----

Half of the

world’s 49 Muslim-majority countries have additional laws banning apostasy, meaning people may be punished for

leaving Islam. All countries with apostasy laws are Muslim-majority except

India. Apostasy is often charged along with blasphemy.

This class

of religious laws is quite popular in some Muslim countries. According to a

2013 Pew survey, about 75% of respondents in

Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia favour making

sharia, or Islamic law, the official law of the land.

Among those

who support sharia, around 25% in Southeast Asia, 50% in the Middle East and

North Africa, and 75% in South Asia say they support “executing those who leave

Islam” – that is, they support laws punishing apostasy with death.

The

Ulema and the State

My 2019

book “Islam, Authoritarianism, and

Underdevelopment”

traces the root of blasphemy and apostasy laws in the Muslim world back to a

historic alliance between Islamic scholars and government.

Starting

around the year 1050, certain Sunni scholars of law and theology, called the

“ulema,” began working closely with political rulers to challenge what they considered

to be the sacrilegious influence of Muslim philosophers on society.

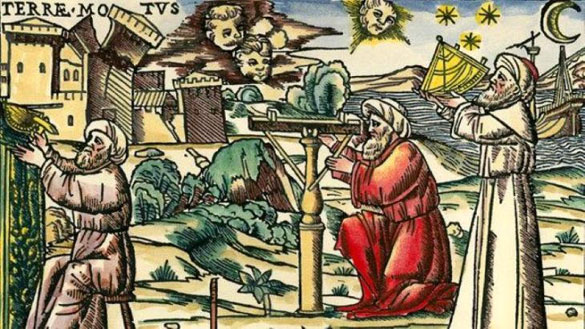

Muslim

philosophers had for three centuries been making major contributions to mathematics, physics and medicine. They developed the Arabic number system used across the West today and

invented a forerunner of the modern camera.

A conspiracy against Sunni Islam? For three centuries,

Muslim philosophers had been making major contributions to mathematics, physics

and medicine, developing the Arabic number system used across the West today

and inventing a forerunner of the modern camera. Yet the conservative ulema

felt these philosophers were inappropriately influenced against Sunni beliefs

by Greek philosophy and Shia Islam. Their views were reinforced by the

brilliant and respected Islamic scholar al-Ghazali, who declared two long-dead

leading Muslim philosophers, Farabi and Ibn Sina (a.k.a. Avicenna), apostates

for their unorthodox views on God’s power and the nature of resurrection. Their

followers, al-Ghazali wrote, could be punished with death

------

The

conservative ulema felt that these philosophers were inappropriately influenced

by Greek philosophy and Shia Islam against Sunni

beliefs. The most prominent in consolidating Sunni orthodoxy was the brilliant

and respected Islamic scholar Ghazali, who died in the year 1111.

In several

influential books still widely read today, Ghazali declared two long-dead

leading Muslim philosophers, Farabi and Ibn Sina, apostates for their

unorthodox views on God’s power and the nature of resurrection. Their

followers, Ghazali wrote, could be punished with death.

As

modern-day historians Omid Safi and Frank Griffel assert, Ghazali’s declaration

provided justification to Muslim sultans from the 12th century onward who

wished to persecute – even execute – thinkers seen as threats to conservative

religious rule.

This

“ulema-state alliance,” as I call it, began in the mid-11th century in Central

Asia, Iran and Iraq and a century later spread to Syria, Egypt and North

Africa. In these regimes, questioning religious orthodoxy and political

authority wasn’t merely dissent – it was apostasy.

Wrong

Direction

Parts of

Western Europe were ruled by a similar alliance between the Catholic Church and

monarchs. These governments assaulted free thinking, too. During the Spanish

Inquisition, between the 16th and 18th centuries, thousands of people were

tortured and killed for apostasy.

Blasphemy

laws were also in place, if infrequently used, in various European countries

until recently. Denmark, Ireland and Malta all recently repealed their laws.

But they

persist in many parts of the Muslim world.

In

Pakistan, the military dictator Zia ul Haq, who ruled the country from 1978 to

1988, is responsible for its harsh blasphemy laws. An ally of the ulema, Zia updated blasphemy laws – written by British colonizers to

avoid interreligious conflict – to defend specifically Sunni Islam and

increased the maximum punishment to death.

From the

1920s until Zia, these laws had been applied only about a dozen times. Since then they have become a

powerful tool for crushing dissent.

Some dozen

Muslim countries have undergone a similar process over the past four decades,

including Iran and Egypt.

Dissenting

Voices in Islam

The

conservative ulema base their case for blasphemy and apostasy laws on a few

reported sayings of Prophet Muhammad, known as hadith, primarily: “Whoever changes his religion, kill

him.”

But many

Islamic scholars and Muslim intellectuals reject this view as radical. They

argue that Prophet Muhammad never executed anyone for apostasy, nor encouraged

his followers to do so.

Nor is

criminalizing sacrilege based on Islam’s main sacred text, the Quran. It

contains over 100 verses encouraging peace, freedom of conscience and religious

tolerance.

In chapter

2, verse 256, the Quran states, “There is no coercion in religion.” Chapter 4,

verse 140 urges Muslims to simply leave blasphemous conversations: “When you

hear the verses of God being rejected and mocked, do not sit with them.”

By using

their political connections and historical authority to interpret Islam,

however, the conservative ulema have marginalized more moderate voices.

Reaction

to Global Islamophobia

Debates

about blasphemy and apostasy laws among Muslims are influenced by international

affairs.

Across the

globe, Muslim minorities – including the Palestinians, Chechens of Russia,

Kashmiris of India, Rohingya of Myanmar and Uighurs of China – have

experienced severe persecution. No other religion is so widely targeted in so

many different countries.

Alongside

persecution are some Western policies that discriminate against Muslims, such

as laws prohibiting headscarves in schools and the U.S. ban on travellers from several

Muslim-majority countries.

Such

Islamophobic laws and policies can create the impression that Muslims are under

siege and provide an excuse that punishing sacrilege is a defines of the faith.

Instead, I

find, such harsh religious rules can contribute to anti-Muslim stereotypes.

Some of my Turkish relatives even discourage my work on this topic, fearing it

fuels Islamophobia.

But my

research shows that criminalizing blasphemy and apostasy is more political than

it is religious. The Quran does not require punishing sacrilege: authoritarian

politics do.

-----

Ahmet T. Kuru is Porteous Professor of Political

Science at San Diego State University, and FORIS scholar at Religious Freedom

Institute. Author of "Secularism and State Policies toward Religion: The

United States, France, and Turkey" and co-editor of "Democracy,

Islam, and Secularism in Turkey", his works have been translated into

Arabic, Bosnian, Chinese, French, Indonesian, and Turkish.

---------

CGI Influencers: When the ‘People’

We Follow On Social Media Aren’t Human

By

Francesca Sobande

October 1,

2021

Social

media influencers – people famous primarily for posting content online – are

often accused of presenting artificial versions of their lives. But one group

in particular is blurring the line between real and fake.

Created by

tech-savvy teams using computer-generated imagery, CGI or virtual influencers

look and act like real people, but are in fact merely digital images with a

curated online presence.

Virtual

influencers like Miquela Sousa (known as Lil Miquela) have become

increasingly attractive to brands. They can be altered to look, act, and speak

however brands desire, and don’t have to physically travel to photo shoots – a particular draw

during the pandemic.

But what

can be a lack of transparency about who creates and profits from CGI

influencers comes with its own set of problems.

CGI

influencers mirror their human counterparts, with well-followed social media

profiles, high-definition selfies, and an awareness of trending topics. And

like human influencers, they appear in different body types, ages, genders and

ethnicities. A closer look at the diversity among CGI influencers – and who is

responsible for it – raises questions about colonialism, cultural

appropriation, and exploitation.

Human

influencers often have teams of publicists and agents behind them, but

ultimately, they have control over their own work and personality. What happens

then, when an influencer is created by someone with a different life experience,

or a different ethnicity?

For

centuries, black people – especially women – have been objectified and

exoticised by white people in pursuit of profit. While this is evident across

many sectors, the fashion industry is particularly known for appropriating and

commodifying black culture in ways that elevate the work and status of white

creators. The creation of racialised CGI influencers to make a profit for

largely white creators and white-owned businesses is a modern example of this.

Questions

of Authenticity

The sheen

of CGI influencers’ surface-level image does not mask what they really

symbolise – demand for marketable, lifelike, “diverse” characters that can be easily altered to suit

the whims of brands.

I recently

gave evidence to a UK parliamentary inquiry into influencer culture, where I

argued that it reflects and reinforces structural inequalities, including

racism and sexism. This is evident in reports of racial pay gaps in the

industry, and the relentless online abuse and harassment directed at black

women.

CGI

influencers are not exempt from such issues – and their existence raises even

more complex and interesting questions about digital representation, power, and

profit. My research on CGI influencer culture has explored the relationship

between racialisation, racial capitalism and black CGI influencers. I argue

that black CGI influencers symbolise the deeply oppressive fixation on,

objectification of, and disregard for black people at the core of consumer

culture.

Critiques

of influencers often focus on transparency and their alleged “authenticity”.

But despite their growing popularity, CGI influencers – and the creative teams

behind them – have largely escaped this scrutiny.

As more

brands align themselves with activism, working with supposedly “activist” CGI

influencers could improve their optics without doing anything of substance to

address structural inequalities. These partnerships may trivialise and distort

actual activist work.

When brands

engage with CGI influencers in ways distinctly tied to their alleged social

justice credentials, it promotes the false notion that CGI influencers are

activists. This deflects from the reality that they are not agents of change

but a by-product of digital technology and consumer culture.

Keeping

It Real

The

Diigitals has been described as the world’s first modelling agency for virtual

celebrities. Its website currently showcases seven digital models, four of whom

are constructed to appear as black through their skin colour, hair texture, and

physical features.

The roster

of models includes Shudu (@shudu.gram) who was developed to resemble a

dark-skinned black woman. But it has been argued that Shudu, like many other

CGI models, was created through the white male gaze – reflecting the power of

white and patriarchal perspectives in society.

Shudu’s

kaleidoscope of Instagram posts include an image of her wearing earrings in the

shape of the continent of Africa.

One photo

caption reads: “The most beautiful thing about the ocean is the diversity

within it.” This language suggests Shudu is used to show how Diigitals “values”

racial diversity – but I argue the existence of such models shows a disrespect

and distortion of black women.

Creations

like Shudu and Koffi (@koffi.gram), another Diigitals model, I would argue,

show how the objectification of black people and the commodification of

blackness underpins elements of CGI influencer culture. Marketable mimicry of

black aesthetics and the styles of black people is apparent in other industries

too.

CGI

influencers are another example of the colonialist ways that black people and

their cultures can be treated as commodities to be mined and to aid commercial

activities by powerful white people in western societies.

Since I

began researching this topic in 2018, the public-facing image of The Diigitals

has notably changed. Its once sparse website now includes names of real-life

muses and indicates its ongoing work with black women. This gesture may be

meaningful and temper some critiques of the swelling number of black CGI

influencers across the industry, many of which are not apparently created by

black people.

A more

pessimistic view might see such activity as projecting an illusion of racial

diversity. There may conceivably be times when a brand’s use of a CGI

influencer prevents a real black influencer from accessing substantial work.

The Diigitals working with actual black people as “muses” is not the same as

black people creating and directing the influencer from its inception. However,

it is important to recognise the work of such real black people who may be

changing the industry in impactful ways that are not fully captured by the term

“muse”.

To me, many

black CGI influencers and their origin stories represent pervasive marketplace

demand for impersonations of black people that cater to what may be warped

ideas about black life, cultures, and embodiment. Still, I appreciate the work

of black people seeking to change the industry and I am interested in how the

future of black CGI influencers may be shaped by black people who are both

creators and “muses”.

----

The

Conversation approached The Diigitals for comment, and founder Cameron-James

Wilson said: “This article feels very one-sided.” He added: “I don’t see any

reference to the amazing real women involved in my work and not having them

mentioned disregards their contributions to the industry”. The Diigitals did

not provide further comment. The article was expanded to make a more

substantial reference to the real women The Diigitals works with.

Source: The Conversation

URL: https://www.newageislam.com/islamic-sharia-laws/blasphemy-sharia-pakistan-non-muslims/d/125560

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic

Website, African Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism