Contention And Reconciliation: Shah Waliullah On The Understanding Of Intellectual Disagreements

By

Mohammad Ali, New Age Islam

April 3,

2022

Qutubuddin

Ahmad Waliullah Works Encompass Almost All Islamic Disciplines Such As Quranic

Sciences, Hadith Sciences, Jurisprudence, Sufism, As Well As Philosophy, And

History

Main

Points:

1. This article

discusses Shah Waliullah’s position on why ulama are likely to have contending

views

2. This also

discusses Shah Waliullah’s advice on how to deal with them

3. Finally, it

draws the attention of the contemporary ulama to Waliullah’s advice which can

help reduce sectarian differences

-----

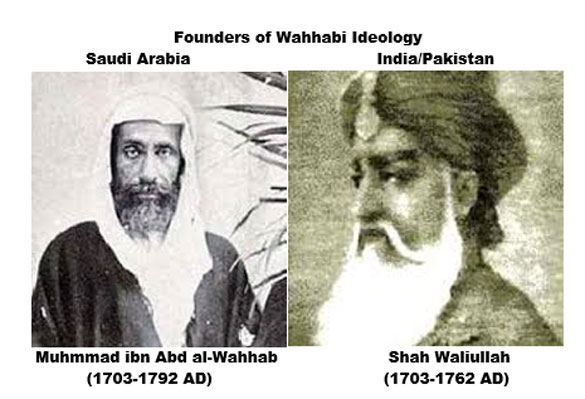

Qutubuddin Ahmad Waliullah (d.1762), commonly known as Shah Waliullah of Delhi, was one of the most illustrious Muslim theologians who lived in the 18th century in India. He was a prolific writer. His work encompasses almost all Islamic disciplines that were taught and studied during his time, such as Quranic sciences, Hadith sciences, jurisprudence, Sufism, as well as philosophy, and history. Due to the ingenuity of his work, the name of Waliullah has become synonymous with Islamic orthodoxy to the Ulama, irrespective of their sectarian affiliations, of the Indian subcontinent, which means that in order to establish authenticity in their interpretations of Islam, contemporary Ulama seek an agreement, a continuity, between his and their opinions. Waliullah produced several remarkable works. A common trait of his scholarship is to obtain reconciliation among contending views of different schools of theology, jurisprudence, and spirituality. Two of such contending views on which Muslim Ulama debated and disputed for centuries are Wahdatul Wujūd and Wahdatul Shuhūd. Both concepts are infused with complex metaphysical philosophies that philosopher-Sufis developed over the years. Renowned Sufi, Ibn Arabi (d.1240), is characterized as the most important thinker who discussed in detail the doctrine of Wahdatul Wujūd. However, Wahdatul Shuhūd was developed by an Indian theologian-Sufi, Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (d.1624), also known as Mujaddid-i-Alif Thani, as an alternative doctrine to that of Ibn Arabi. These two doctrines caused a deep rift among the mainstream Sufis and Ulama for a long period of time. In a letter that he wrote to a Medina-based scholar, Shaikh Abu Tahir al-Kurdi al-Madni, Waliullah tried to build a discourse on the possibility of harmony between the two doctrines. This letter is entitled as Faisla-e-Wahdatul Wujūd wa Wahdatul Shuhūd and is incorporated in his book, al-Tafhīmatul Ilāhiya.

This is a

long letter, which touches on various points concerning the discussion. But

this is not why I intend to discuss it in this essay. Rather, I would like to

discuss the significant insights that Waliullah shares in the opening of the

latter regarding the difference of opinions that Ulama are likely to have in

matters of religion. It is an important question that Muslim Ulama paid

attention to previously, so that they may not become insistent on a particular

opinion about a controversial issue. As we will see, Waliullah discusses that

differences in the opinions of Ulama and scholars occur because of certain

conditions that they are bound to and that a person’s view cannot define, for

instance, the nature of the reality of something in its entirety that he is

trying to make sense of. Such a position instils a scholar with humility. We

find no such discourses among Ulama today, which is one among many reasons that

explain why Ulama in our societies are so stubborn and arrogant. To them, their

opinion alone holds the truth, while opinions of other Ulama are erroneous and

lead to heresy.

Before

delving into the interpretation of Wahdatul Wujūd and Wahdatul Shuhūd

and locating the points where the two doctrines can be harmonized, Waliullah

explains that every age is unique in terms of its time, meaning the conditions

that are specific to time and are changed with the change of time and the

change of people and their necessities. And every age produces its own

knowledge. Then he urges his reader to ponder upon the conditions of the

earliest Muslim community in the Arabian Peninsula. At that point in time,

neither Islamic sciences were developed nor there were many discussions about

them. In later years, Muslim scholars developed knowledge according to their

necessities. They differed and contended on many issues. In our time, we have

inherited their knowledge, the knowledge of theologians, philosophers, and

Sufis. Their knowledge came to us in such a form that many of their contentious

issues had already been reconciled, and we find it organized as if everything

is properly placed in a unified system.

He then

argues that the divine encompasses infinite reality. It is like a vast ocean

that is without any beginning and end. And those who venture to comprehend such

a vast ocean are like tiny particles. If they are dipped into it, they would

change nothing in the ocean.

Waliullah

uses this analogy to illustrate that Allah or the nature of His Being is a

metaphysical reality that our finite senses cannot fully comprehend. To further

explain his point, he also uses another analogy of a huge tree that some blind

people try to understand by touching its different parts. As a result, based on

the little knowledge that they could procure because of their sense of touch,

they come to formulate different opinions about what a tree is. Waliullah says

that based on the knowledge that they have they are entitled to formulate their

opinions and differ from each other. But if one of them insists that only his

opinion is true, that person is misguided. Because he is trying to impose his

own opinion, which holds the knowledge of only one aspect of reality, as a

comprehensive understanding of the reality, which in fact is not the case. We

can generalize this argument and do not need it to limit to the infinite Being

of God, meaning similar to the Being of God, other realities uphold the same

complexities. Our limited resources can touch only one or some aspects of those

realities, hence, differences among scholars are unavoidable. Waliullah says

that those who are capable of placing those opinions in their right places and

are open to recognizing all of them are successful people. And those who are

fixed upon a single opinion or interpretation cause chaos and confusion.

Waliullah’s

explanation of the causes that lead to contentions and his advice about how we

should deal with them is enlightening. In the absence of such insights, Muslim Ulama

have become rigid in following their particular schools. In Waliullah’s time,

Muslims were divided into various schools of thought as well, and he tried to

bridge this division by explaining that their division was based on mere

confusion. The reform that Waliullah was trying to introduce, according to some

scholars, was disrupted by the establishment of colonialism. The people that

followed him created more divisions among them. The modern South Asian Muslim

sects did not exist in his time. However, the causes that led to their

emergence existed which he explained in his works, and which we have discussed

here. It is unfortunate that ulama did not pay attention to his advice. They

are like the blind people in Waliullah’s analogy who are trying to understand

Islam. They can comprehend but only some aspects of the religion. However,

their arrogance and ignorance do not allow them to recognize it. Ulama in every

sect claim that only their understanding of religion is true, while the

understanding of others is heresy or blasphemy. Ulama needs to open their minds

to the opinions of others, i.e., ulama of other sects as well as non-ulama

scholars. This will not only widen their horizons but also reduce the air of

hostility among different sects and schools of thought.

----

Mohammad

Ali has been a madrasa student. He has also participated in a three years

program of the "Madrasa Discourses,” a program for madrasa graduates initiated

by the University of Notre Dame, USA. Currently, he is a PhD Scholar at the

Department of Islamic Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. His areas of

interest include Muslim intellectual history, Muslim philosophy, Ilm-al-Kalam,

Muslim sectarian conflicts, madrasa discourses.