Did We ‘Win’ Our Freedom or The British ‘Gave’ It to Us? Reading History from Diplomats’ Lens

By

Jaithirth Rao

04 October,

2023

In

post-independence India, former diplomats Chandrashekhar Dasgupta and Narendra

Sarila emerged as eminent and important historians. The chronicling of the

20th-century India would be poorer in the absence of their works. Additionally,

we would have missed out on facts and analyses of enormous significance.

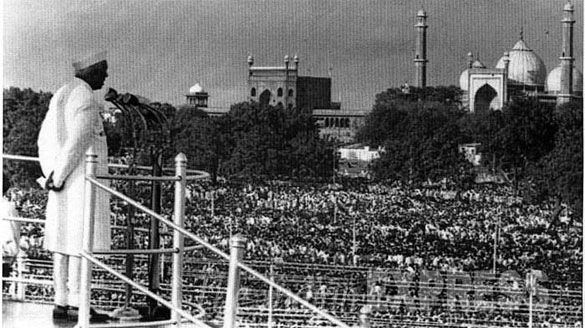

Prime Minister Nehru addresses the nation from the Red Fort on 15 August

1947 | Wikimedia Commons

------

Let us

start with Sarila, whose The Shadow of the Great Game looks at Indian

Independence, the Partition, and the integration of princely states not through

romantic, personality-focused, hyper-patriotic or sanctimonious lenses. For

Sarila, the Independence and Partition were both inevitable consequences of the

attitudes and decisions of Britain, the retreating imperial power. Our

historians have endowed Indian leaders with greater agency than they actually

possessed.

For

Britain, leaving India was primarily about the loss of its value in strategic

terms. India had been a vast reservoir of military manpower for Britain and its

empire. But this crucial resource was becoming increasingly unreliable as

demonstrated by the creation of the Indian National Army (INA) and mutinies in

the Royal Indian Navy. India’s importance in maintaining communication lines

with the white dominions of Australia and New Zealand had declined dramatically

as airpower had assumed increasing importance. Airbases in India might be

valuable. But rights to overfly may in fact be sufficient and even that may not

be necessary if Ceylon was a friendly country. The decision to leave India,

which was becoming a political headache and not sufficiently beneficial in

economic terms anymore, was then taken by the British elite in cold and

unemotional terms. This would also help quell the problems arising from the

increasing American pressure for “freeing” colonies, especially now that the US

was the senior partner of the Anglo-American alliance.

The

decision to leave India was not taken hastily after the end of World War 2.

Sarila lucidly documents the case that despite Winston Churchill’s obduracy,

the second last Viceroy, Archibald Percival Wavell, was studiously putting

together plans for British withdrawal in different scenarios. The problem that

Wavell and most senior British military analysts faced was that the “Russian

bogey” of the 19th century and the fear of Russia invading India had been

overtaken by the “Soviet bogey” of the mid-20th century and the new fear was

that the Soviets would invade the oilfields of the Middle East. How could the

western alliance protect itself against that? It is this concern that ensured

Britain’s pro-active approach to the creation of Pakistan.

While most

Pakistani and Indian scholars are of the opinion that Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s

resolution or obstinacy was one of the major causes of partition, Sarila puts

together a well-documented account to argue that rather than being an actor

with independent agency, Jinnah was in fact manipulated by Linlithgow (Viceroy

from 1936 to 1943) and Wavell. Similarly, while Mahatma Gandhi’s possibly

ill-conceived Quit India movement may have resulted in the hardening of British

prejudice against the Congress and its public plea for Indian unity, it appears

that the Congress may have played into the hands of the British. Among other

things, through the war years, they were able to resist American pressure for

early Indian independence by painting the picture that the Congress’ actions

were pro-Japanese and pro-Axis.

Sarila’s

research quite clearly shows that while many British decision-makers were

sympathetic to the Muslim League, on balance, they remained in favour of a

united India. They kept portraying the Muslim League as a useful nuisance that

could later be bottled up. Something changed after 1945 with the incipient

beginnings of a new Cold War. India was no longer all that important.

Middle-eastern oil was important and crucially, territories that could be used

to prevent a Soviet thrust towards the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf had

become a central strategic concern. In this context, a united India may have

been a problem rather than an advantage. Between Gandhi’s non-violence and the

Congress party’s socialist stance, the likelihood that western allies would be

allowed to maintain airbases or shipping facilities in India was becoming

dimmer by the day.

Jinnah’s

Pakistan, on the other hand was openly committing itself to the western cause

and to an anti-communist alliance. Northwestern India, if clearly in the

western camp, would be ideal and quite sufficient to checkmate the Soviets.

Ergo: Partitioning India was a good idea. Sarila has referred to documents

where even the redoubtable Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, whose primary

interest was in the European theatre, went along with this idea. The British

had come up with a neat solution from their point of view. The Indian headache

was gone. The crucial territories needed to block the Soviets remained in the

western camp. The fact that this cold, calculating approach may result in

enormous human costs that would be borne by the native subjects of British

India was not even discussed or considered. This assessment should sober up even

the most emotional among us who are busy trying to fix the “blame” for

partition among our hapless leaders, who emerge as instruments more than as

agents. The curious lack of interest on the part of the British for the fate of

the partitioned territories of eastern India almost ominously anticipates

Kissinger’s disdain for the “basket-case” of Bangladesh. Strategic value

counted, and in that calculus, East Pakistan was a footnote.

The next

time our young students read NCERT textbooks, which tell them about how we

“won” our freedom in a glorious manner, they might want to get their parents to

read aloud to them some extracts from Sarila’s book. Rather than winning it, we

may have been “given” our freedom so that our former rulers could have one

headache less. A year later, they got rid of a stomach ache when they gave up

their mandate in Palestine, whose conquest General Edmund Allenby had been so

proud of just three decades earlier. It may also be noted that there were no

Indian soldiers available for Britain in 1948 unlike in 1918. Our

schoolchildren should perhaps also be told that the evil British did not create

Pakistan out of spite. They simply exploited existing fault lines in our

society to achieve cold, strategic objectives. And who can say, they were

wrong? For more than four decades, Pakistan remained a steadfast anti-Soviet

ally of the west and helped considerably in bringing about the dissolution of

the USSR. Pakistan was also crucial in helping bring about the Nixonian détente

with China. Pretty good returns for an investment made almost nonchalantly in

1947, one would think.

The former

diplomat authored two brilliant books, one about the 1948 Kashmir conflict and

another about the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Published in 2002, War and

Diplomacy in Kashmir: 1947-48 makes the case that it was not Jinnah’s

over-optimism or Nehru’s timidity that resulted in the denouement of a frozen

Kashmir. The Kashmir issue zig-zagged in different directions and finally ended

in a manner that was key to British interests. While India needed to be

placated a bit here and there, the key requirement was to ensure that, at the

end of it all, India should not be in a position to strangle Pakistan. The

British were quite willing to let Indians and Pakistanis fight it out. It was

almost as if they were smug coaches watching two children learn to box in a

ring. When Jinnah wanted the Pakistan Army to intervene directly and not just

with disorganised soldiers masquerading as irregulars, Frank Walter Messervy,

the British general who was the first commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army,

told Jinnah point blank that he would withdraw the British officers. Jinnah

pulled back. General Douglas Gracey, the second chief of the Pakistan Army,

told Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan that he and other British officers would

happily battle Indian forces. What caused the change? That matter is worth

examining.

The other

obdurate Indian potentate, the Nizam of Hyderabad, had many friends in the

British parliament, especially among its Tory members, including Churchill and

the influential Rab Butler. This is one reason that the Nizam kept dreaming of

independence and postponed his accession until Hyderabad was for all practical

purposes conquered by India. Hari Singh, the hapless Maharaja of Kashmir, had

no friends in high places. After all, his desire for independence was no

different from that of the Nizam. But he was unlucky because his kingdom, or at

least parts of it, had what is loosely described as “strategic” value. Having

created Pakistan, there was no way the British would allow the crucial border

with Xinjiang to be with India. One should not forget that in 1947, Kuomintang

China was weak and the Soviets could easily have taken over Xinjiang. A common

border between a potentially socialist, if not openly communist, India and the

USSR was simply not acceptable to the British. The sequence of events is

fascinating. Within two weeks of Hari Singh’s reluctant signature on the

Instrument of Accession, Major William Alexander Brown organised a coup in

Gilgit. Hari Singh’s Dogra troops were overpowered and a telegram was sent out

that Gilgit was joining Pakistan. Brown personally hoisted the Pakistani flag

in Gilgit. Incidentally, Major Brown got a special award from His Majesty, the

King of Great Britain. To this day, no one knows what the award was for.

History buffs are welcome to speculate whether the more recent phenomena of

colour revolutions bear any resemblance to Brown’s bogus coup.

Gilgit and

its neighbouring Baltistan were just too remote to justify immediate action.

But the Indian Army successfully pushed back the invaders from the vale of

Kashmir and consolidated its hold. General KS Thimayya was now pushing his

troops to gather up the rest of Hari Singh’s complicated and disparate kingdom.

All of a sudden, in Pakistan, British officers who earlier had qualms about

fighting in Kashmir on the grounds that Kashmir had legally acceded to India,

were enthusiastic about participating in a war being fought against a sovereign

country, which was even a member of the British Commonwealth. To understand

their reasons, one has only to look at the map. If Thimayya had succeeded in

getting hold of “all of Kashmir”, India would have a border with the North-West

Frontier Province (NWFP), now referred to as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. As Hamlet

would have said, “Ay, there’s the rub”.

The NWFP

was a reluctant entrant in the new Pakistani state. In the 1946 election, the

Congress party had won the state. When India was partitioned, there emerged a

strong constituency for an independent NWFP. The British decision-makers were

haunted by the fear that if India had a border with NWFP, then Pakistan would

be hemmed in. And God forbid (from the British perspective, that is), if NWFP

seceded from Pakistan, then their all-important anti-Soviet buffer state would

disappear. The British had no interest in supporting a Pakistan bereft of the

NWFP and the western parts of the Kashmir state. They had every interest in

preserving these regions as the territory of their emerging natural ally. They

frankly could not care less what happened in the eastern part of Hari Singh’s

kingdom. If that remained with India, then so be it.

Dasgupta

successfully makes the case that under no circumstances would the British have

allowed India to move much further west. The simple fact that we were dependent

on the British for our arms could and did ensure that. Again, one can only

marvel at the enduring success of the British plan. Seventy-six years later,

all that has happened is the changing of some names. Otherwise, western Kashmir

and NWFP remain with their most allied of allies and India gets to keep the

eastern part, thank you very much. And lest some readers think that all this is

boring history, I suggest that they just look at the map and see where the

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor runs; more interestingly, ponder over the US

Ambassador to Pakistan’s recent visit to Gilgit. Strategy counters all. Indian

sensitivities are met with a nonchalant shrug of the shoulders.

Dasgupta

has done considerable research on the happenings in the UN where our idealistic

first Prime Minister lodged a complaint and hoped for justice. Based on a plain

legal reading, the US was very sympathetic to India’s position that any future

course of action was contingent on Pakistan withdrawing its troops, which were

illegally stationed in Kashmir. Perhaps, the American officials assigned to

this matter were too junior in their State Department. They were not aware of

the high-level decisions being orchestrated by their ally, la perfide Albion.

The British repeatedly and successfully ensured that the original Indian

complaint regarding Pakistani invasion was never addressed. Instead, they

converted the whole issue into an almost childish and comical “dispute” between

two equally aggrieved parties and not one between an aggressor and a defender.

The leader of the British delegation, a Machiavellian intriguer called Philip

Noel Baker, cleverly manipulated the discourse in order to ensure this outcome.

The sober British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, was more sympathetic to India

and to Nehru. But he also gave in on the altar of the “strategic imperatives”

of the anti-Soviet allies.

Incidentally,

until 1947, most leaders in the British Labor Party were pro-Congress and pro-India

in their sympathies. It was the Tories who were on the side of the Muslim

League and Pakistan. But 1947 changed that. Labor leaders like Ernest Bevin and

oily politicos like Noel Baker were becoming explicitly anti-India and

supporters of a grand west-led alliance with Islamic states. Again, history

buffs might be intrigued by the parallel with the pro-Pakistan British Labor

Prime Minister, Harold Wilson in the sixties and with today’s British Labor

Party, which is virtually a Pakistani-Islamic propaganda outfit. The same buffs

might also pay attention to the fact that the present dominant left-liberal

discourse was already gaining traction in the fifties when the Scandinavians

awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace to the superficially woolly-headed Noel

Baker.

The key

takeaway from the books of Sarila and Dasgupta is that prior to independence

and immediately afterwards, the agency of our leaders was severely constrained

and limited. There is little point in writing page after page praising or

blaming our so-called great leaders for happenings that were largely beyond

their control. Sarila and Dasgupta cover history going back seven to nine

decades. Despite their personal charismas, Gandhi and Nehru led a subject

country and a weak newly independent one. They may have tried with the best of

intentions and energies. But Independence, Partition and Kashmir were largely

determined by the needs of the departing British who were still very much in

control.

As we look

back at the journey of Independent India, we can now see the gradual increase

in the strength of our own agency. We can have nothing but admiration for so

many of our leaders over the years, who have successfully ensured that in

substantial measure, we control our destiny. Dasgupta’s second book, India and

the Bangladesh Liberation War, captures the adroitness with which Indira Gandhi

charted our country’s course in 1971. Vajpayee’s break-out from the nuclear

apartheid imposed on us is a more recent example. But I think we should not

forget less publicised but crucial acts like Morarji Desai’s stubborn refusal

to be swayed by Jimmy Carter’s hectoring when the US President tried to

arm-twist us into agreeing to nuclear abstinence. Narendra Modi’s recent

efforts to strengthen our own defence production establishment is another

heartening development. The best tribute we can pay to figures like Sarila and

Dasgupta is to maintain an Arjuna-like focus on defending and embellishing our

national agency.

------

Jaithirth

Rao is a retired businessperson who lives in Mumbai. Views are personal.

(Edited

by Prashant)

Source: Did

We ‘Win’ Our Freedom Or The British ‘Gave’ It To Us? Reading History from

Diplomats’ Lens

URL: https://newageislam.com/spiritual-meditations/freedom-british-history-diplomats/d/130821

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism