Sufi Al-Hajj Wali Akram: 20th Century Black American Muslim Pioneer

By Rasul Miller

March18,

2020

Black

American Muslims engage virtually every kind of Islam: Sunni, Shia,

traditional, reformist, orthodox, heterodox, and whatever else one might

imagine. Therefore, it is not surprising that many Black American Muslims have

embraced Sufism.

They can be

observed marching in the parade with Senegalese members of the Mouride order on

Amadou Bamba day in Harlem. In Chicago, Black American members of the Haqqani

Naqshbandi order can be seen wearing bright red turbans at the suggestion of

their Turkish Cypriot spiritual guide, Shaykh Nazim al-Haqqani, who commented

on the beautiful, “fiery” nature of Black spirituality1. nd, distinguished

Muslim scholars like Ustadha Ieasha Prime and Imam Amin Muhammad connect

spiritual seekers in the United States to the rich tradition of the Ba ‘Alawi

order in Yemen, who helped spread Islam across the Indian Ocean.

There is

also considerable evidence of Sufi practice among enslaved African Muslims in

the Americas because Sufism was, and continues to be, a hallmark of the Muslim

societies from which many were taken captive during the Transatlantic slave

trade.

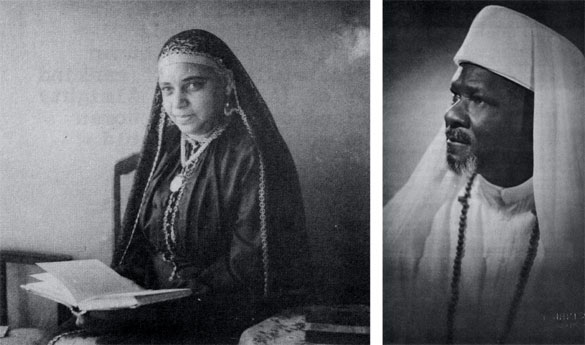

Mother Khadijah & Shaykh

Daoud. From the digital archive of the estate of Imam Mohamed Kabbaj.

------

Although

Sufism re-emerges in Black American Muslim communities during the early 20th

century, in a number of contemporary Black Muslim communities, Sufis are viewed

with suspicion. Part of the reason for this is the rise, during the 1990s, of a

generation of Black American Muslims exposed to the Salafi movement through

travel and increased access to English translations of religious literature

exported from the Gulf Arab States. In particular, many young, Black American

Muslim men who studied at the Islamic University of Medina in Saudi Arabia

began teaching and prostelitising in major cities on the East Coast with

considerable success. As a result of this rising Salafi influence, many became

leery of Sufism and questioned its compatibility with orthodox Islam. This

added to an earlier attitude of suspicion against Sufism and foreign Sufi

Shaykhs that emerged among some Black American Muslims in the aftermath of the

tumultuous fracture of the Darul Islam Movement (the Dar). Despite these

dynamics, Sufism continues to be an integral part of orthodox Muslim religious

life for those Black American Muslims who embrace it, and a testament to their

desire for spiritual fulfilment and transformation. What follows is a brief

overview of Black American Muslim engagement with Sufism during the 20th

century.

Sufism among 20th Century Muslim Pioneers

Two of the

most prominent pioneers of orthodox Islam in 20th century America were Shaykh

Daoud Ahmed Faisal and Al-Hajj Wali Akram. I refer to these men as “orthodox”

pioneers to align with the everyday language of many Black American Muslims

during the early 20th century. At the time, Black American Muslims

distinguished “orthodox” groups of Muslims from those that they considered

heterodox, such as the Nation of Islam and the Moorish Science Temple, and were

less likely to distinguish between “Sunni” and “Shi’a” Muslims.

Shaykh

Daoud was born on the Caribbean island of Grenada in 1891. At the age of 21, he

relocated to New York City to study music. In 1924, he married a Bermudan

vocalist who later adopted the name Khadijah. By 1928, Shaykh Daoud had

accepted Islam and opened the Islamic Propogation Society, one of the city’s

first organizations founded for the purpose of promoting Islam. Together,

Shaykh Daoud and Mother Khadijah founded a mosque called the Islamic Mission of

America in Brooklyn in 1939. Shaykh Daoud joined the Shadhili order, possibly

as early as the beginning of the same decade, and was likely introduced to it by

Ethiopian and Somalian Muslims in Harlem in the 1930s.2 He deepened his

connections to it through Yemeni Muslim merchant seamen who attended his

Brooklyn mosque in the 1940s.

The many

Arab, South Asian and East African merchant seaman who encountered the mosque

spread word about Shaykh Daoud’s and Mother Khadijah’s efforts through a global

network of Muslim seafaring workers, prompting others to visit his mosque when

their ships docked at the nearby Brooklyn Bridge piers. Shaykh Daoud went on to

become a muqaddam (an official representative) of the Shadhili order. According

to one close friend and aide, Shaykh Daoud received a written authorization

from the renowned Moroccan Sufi Shaykh Ahmed al ‘Alawi, which Shaykh Daoud used

to carry with him inside his kufi.

Another

giant of early 20th century orthodox Islam, Imam Al-Hajj Wali Akram, who

founded the First Cleveland Mosque in 1937, introduced members of his

congregation to the Chishti order during the 1950s. According to members of his

family, Imam Akram embraced the order while traveling throughout the Arab

World, South Asia and Eastern Europe after completing his celebrated pilgrimage

to Mecca in 1957. Unlike Shaykh Daoud, whose Sufi affiliation was unknown to

most members of his congregation, Al-Hajj Wali Akram held gatherings for the

observance of the Chishti dhikr (devotional remembrance) in his mosque. This

likely marks the first public Sufi gathering convened by Black American Muslims

in a mosque during the 20th century.

Wali Akram at home in Cleveland,

Ohio. 1990. copyright Jolie Stahl

------

The 1970s

and Onward

During the

1970s in New York City, three Black Muslim Sufi communities emerged that went

on to amass a national following: the Tijaniyyah, Qadiriyyah and Burhaniyyah.

These three groups provided many Black American Muslims with their first

exposure to a traditional Sufi order. The first of these was the Tijani order.

Many of the first Black American Tijanis came from the Mosque of Islamic

Brotherhood (MIB) in Harlem and the Islamic Cultural Center of New York

(ICC-NY) in Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Two of the earliest members were Imam

Sayed Abdus-Salaam, co-founder and assistant Imam of MIB, and Hajjah Kareemah

Abdul-Kareem, an attendee of ICC-NY who became prominent in the city’s Muslim

community due to her philanthropy.3 They were introduced to the Tijani order by

a young Senegalese religious scholar named Shaykh Hassan Cisse, who first

visited the United States in 1975. Shaykh Hassan’s exceptional Islamic

scholarship, fluency in English and pan-African political sensibility made him

especially attractive to Black American orthodox Muslims interested in the

legacy of Islam in West Africa.

In the

subsequent decades, Shaykh Hassan emerged as the world’s preeminent

representative of the Tijani order. But during the 1970s and early 1980s, while

in the early stages of his career, he spent significant time with Black

American adherents in New York City, Detroit and Chicago. He appointed dozens

of Black Americans in various cities as Muqaddams of the Tijani order. As a

result, the order took root in urban centres throughout the country, spreading

to cities like Atlanta, Washington D.C., Cleveland and Denver, thus creating a

distinctly Black American Sufi congregation. The Tijani order furthered its

reach with the founding of the African American Islamic Institute in 1984, a

Qur’an school in Senegal that hundreds of Black American Muslim children have

attended.

Jama’at of the Shehu. Eid al

Fitr. 2019 copyright Luqmon Abdus-Salaam

------

In the

latter part of the 1970s, some of the leaders of the Dar were introduced to the

Qadiri order by Shaykh Mubarak Ali Gilani from Pakistan.4 The Dar was founded

by Muslims who previously attended Shaykh Daoud’s and Mother Khadijah’s

ethnically diverse mosque in Brooklyn and had learned about the history of

Islam in South Asia from people like Hafiz Mahbub, a Pakistani Qur’an teacher

who served that community. In addition, Imam Yahya Abdul-Kareem, the Imam of

Ya-Sin Mosque in Brooklyn (the Dar’s headquarters) exhibited an interest in

Qadiri texts as early as the 1960s. He and other members of the congregation

became formal adherents of the Qadiri order upon encountering Shaykh Gilani,

who visited the United States in 1978. Shaykh Gilani’s knowledge of African

Diasporic history and his criticism of Western imperial domination of

majority-Muslim countries contributed to his appeal among members of the Dar —

a community characterized by its zeal for Islam and its rejection of Western,

secular, white supremicist cultural norms.

However,

some members were distrustful of Shaykh Gilani and opposed the idea that their

predominantly Black and Latino Muslim congregation should defer to a foreign

religious leader. Subsequently, during the early 1980s, the Dar effectively

split into two communities. The contingent that embraced Shaykh Gilani’s

leadership and his approach to Sufism formed the Jama’at al-Fuqrah (currently

known as The Muslims of America, Inc.), which established rural Muslim

settlements around the United States. that are still active today.

The third

community to emerge during this period was the Burhani order. In 1973, a Black

American Muslim named Shaykh Abdullah Awadallah travelled to Sudan. One of his

traveling companions was the infamous Malachi York, then known as Imam Isa.

Upon their return, York established his Ansar Allah community, a heterodox

Islamic congregation that incorporated aspects of the Sudanese Sufi tradition

along with an eclectic mix of beliefs and practices.5 Shaykh Awadallah, on the

other hand, maintained a commitment to Sunni Islam and cultivated a

relationship with Shaykh Muhammad Osman Abdel Burhani, a well-known spiritual

guide he met in Sudan who then designated Shaykh Awadallah as his American Muqaddam

during the late 1970s. Shaykh Awadallah set up a Zawiya (a community worship

space) in the Bronx that held dhikr regularly.

6th Annual Shaykh Hassan

Cisse Commemoration Courtesy of Nasrul Ilm America.

-----

From the

1980s onward, increasing numbers of Black American Muslims throughout the

United States became interested in other Sufi orders on the African continent.

For instance, during the 1990s, many Black American Muslims learned about the

famed precolonial Nigerian scholar, political leader, and Sufi guide, Shehu

Usman Dan Fodio. They ultimately formed the Jama’at of the Shehu, and embraced

the leadership of his descendants and spiritual heirs in Sudan. This increased

awareness of the legacy of the Shehu was due, in large part, to the efforts of

an African American Muslim named Shaykh Muhammad Shareef bin Farid, founder of

the Sankore Institute of Islamic-African Studies. A prolific translator, he

made scores of works authored by the Shehu and other scholars associated with

him available to the public in English.

Of course,

Black American Muslims can be found in many more Sufi orders than these. They

continue to forge substantive transnational relationships by participating in

global Sufi networks, while simultaneously using the lessons of the Sufi

tradition to address their local communities’ needs. Today, Black American

Muslims explore the wisdom of famous Sufi sages mentioned on the pages of

history who hail from every corner of the globe. Yet, it remains important to

tell the local histories of our Black American Muslim foremothers and

forefathers who engaged Sufism because they can grant us access to a unique

kind of wisdom — one that can help us navigate the ideological differences that

divide Muslim communities in the United States, and around the world, and how

to harness Islam’s transformative potential in our own context.

------

Rasul Miller is a historian of Black Muslim

communities in the Atlantic World. He received his PhD in History and Africana

Studies from the University of Pennsylvania. His research interests include

Muslim movements in 20th century America and their relationship to Black

Internationalism and West African intellectual history. He currently serves as

a Postdoctoral Associate in the study of the Racialization of Islam at Yale

University’s Centre for the Study of

Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration.

Original Headline: The Black American Sufi: A

History

Source: The Sapelo Square

URL: https://newageislam.com/islamic-personalities/sufi-al-hajj-wali-akram/d/123600