Professor Ataullah Siddiqui Of Kalimpong Demonstrated That A Devout Muslim Was Not An Enemy Of Other Faiths

By Samantak Das

20.11.20

Twelve days

ago, a sixty-six-year-old man died in Birmingham, the United Kingdom. He had

been raised in the picturesque hill town of Kalimpong, where, when still a

student at the Scottish Universities Mission Institution (typically abbreviated

to SUMI), he had had the temerity to approach one of the giants of Indian Nepali

literature, Parasmani Pradhan (1898-1986), with a rather strange request. Would

the great man consider translating a scholarly Urdu book on the fundamentals of

Islam into Nepali for the benefit of those who wanted to know about the faith

but lacked Urdu?

Not

surprisingly, the busy scholar did not take the uniformed schoolboy seriously,

and sent him away. But the lad was not to be discouraged so easily. He kept

coming back day after day until Dr Pradhan finally gave in, agreed to read an

English translation of the text, and then took on the task of translating it

into Nepali; which he did with a little help from the boy’s father, the imam of

the only mosque in town, Maulana Muhammad Sibghatullah Siddiqui. The book was

published in 1974, in Nepali, as Islam

Darshan, and Dr Pradhan would later confess that it wasn’t until he had

undertaken the project of translating it that he discovered just how many words

of Urdu, Farsi and Arabic origin had entered the everyday vocabulary of Nepali

speakers.

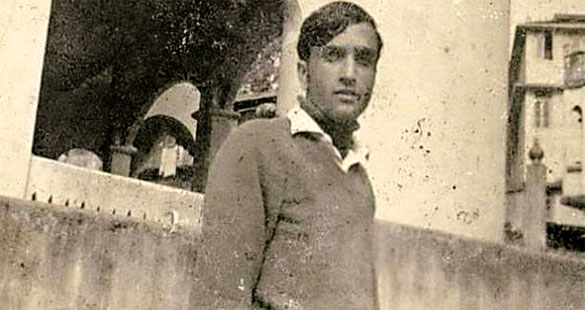

Ataullah Siddiqui as a young

man, in Kalimpong.

Fom his family's collection,

courtesy of Rafat Ali

------

This

incident — narrated to me by his nephew, Professor Rafat Ali, a friend and

colleague — sums up the qualities that went into the making of Professor Ataullah

Siddiqui, a remarkable man who passed away in his prime, with his life’s

mission of bringing about inter-faith understanding and harmony still

incomplete. These qualities, recognized by students, colleagues and friends

across several continents, included doggedness, strength of conviction, an

ability to bring others around to his way of looking at the world, creating

bonds through accepting diversity and difference; and an unflinching faith in

the essential goodness of human beings.

From the

time he left for the UK in the early 1980s as a Research Fellow in the Islamic

Foundation, till his death, when he was Professor of Christian-Muslim Relations

and Inter-Faith Understanding at the Markfield Institute of Higher Education in

Leicestershire, having picked up numerous awards and accolades along the way

(including an honorary doctorate from the University of Gloucestershire),

Professor Siddiqui remained both a devout Muslim as well as a person who

believed in logic, reason, compassion and understanding to build a world where

all faiths could exist in harmony.

His 2007

report to the British Parliament, Islam

at Universities in England: Meeting the Needs and Investing in the Future,

better known as the Siddiqui Report,

begins by invoking “the changed dynamics of relations between Muslims and

policymakers in Western countries” post 9/11 and 7/7 (the July 2005 bombings in

London), then bluntly stating that “it is now equally important that different

experiences and expressions of Islam are explored outside the needs of

diplomacy and the exigencies of the situation in the Middle East”, before going

on to make a set of ten policy recommendations which have unfortunately, as far

as I am aware, still not been implemented in full within the British higher

education system. But that did not deter Professor Siddiqui from his task of

trying to bring about dialogue among individuals from different faiths (or of

no faith).

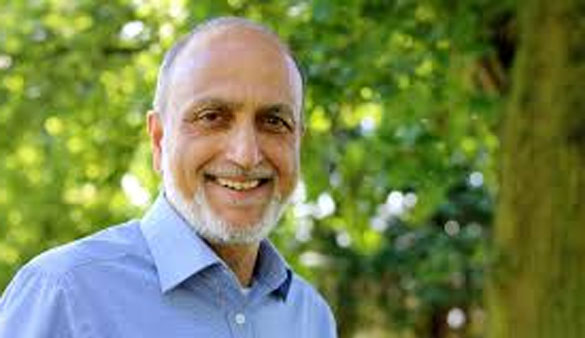

Dr Ataullah Siddiqui is a

Professor of Christian-Muslim Relations and Inter-Faith Understanding at the

Markfield Institute of Higher Education where he was also the Director of the

Institute from 2001 to 2008. He was a founder President and Vice Chair of the

‘Christian Muslim Forum’ in England, and a founder member of the Leicester

Council of Faiths.

-----

In a 2019

talk at the conference on “Leadership, Authority and Representation in British

Muslim Communities” at Cardiff University, Professor Siddiqui had asserted that

since it was enjoined that a mufti (an Islamic jurist) needed to know the urf

and adat, that is the customs and practices of the people, this meant knowing

about the Enlightenment, European history, as well as the religious beliefs and

practices of Judeo-Christian traditions “as part of Islamic Studies” in Europe.

Translated into the Indian context, this would require students of Islam to

know about Indian history, Hinduism, Christianity and other local traditions to

become true alims (scholars) — a point echoed by the imam of Calcutta’s Nakhoda

Masjid, Maulana Shafique Qasmi, at a memorial meeting held for Professor

Siddiqui a few days ago, where he asserted that only people who have not read

their scriptures properly fight over religion and that, in his opinion, the

Gita and the Bible, along with the Quran, ought to be read by madrasa students

as part of their curriculum. Such has been Professor Ataullah Siddiqui’s

influence.

Yet I was

unable to find mention of the man and his work in any major newspaper of the

state where he had been raised and educated. Which is a pity for through his

life and work — and I do not have the space to write about his many books and

articles here — Ataullah Siddiqui had demonstrated that a devout Muslim was not

only not an enemy of other faiths, but rather that it is part of a true

Muslim’s calling to understand, respect, and cooperate with members of the

nation/region/community/locality who hold beliefs that differ from her/his own.

As we seem

to sink ever deeper into bubbles inhabited exclusively by those who think and

act and react like us — a process accelerated by the ongoing pandemic — it is

perhaps even more vital to remember the likes of Ataullah Siddiqui; or, for

that matter, his fellow travellers in faith like Swami Agnivesh and the

shamefully still-imprisoned 83-year-old Father Stan Swamy: three individuals

whose deeply-held religious beliefs encouraged them to fight — in very

different ways — on behalf of precisely those individuals whose beliefs did not

match their own. Their journeys tell us that one can be a true believer without

necessarily demonizing others who are not; that one can pray to a particular

god or gods and still respect those who pray to others or none; that all of us

are, beneath our superficial differences, human beings after all. In so doing,

they encourage us to hold on to that fast-depleting commodity, without which it

is difficult to imagine a civilization worth the name — hope.

-------

Samantak Das is professor of Comparative

Literature, Jadavpur University, and has been working as a volunteer for a

rural development NGO for the last 30 years

Original Headline: Faith matters

Source: The Telegraph India