Justice Syed Mahmood: A Dissident Voice in the Colonial Justice System

By

Grace Mubashir, New Age Islam

15 May 2023

Justice

Syed Mahmood, whose life will never be forgotten in the Indian Judicial annals,

guided Sir Syed's initiatives for educational excellence and was the genius who

gave generously his time and wealth to the Aligarh Muslim University.

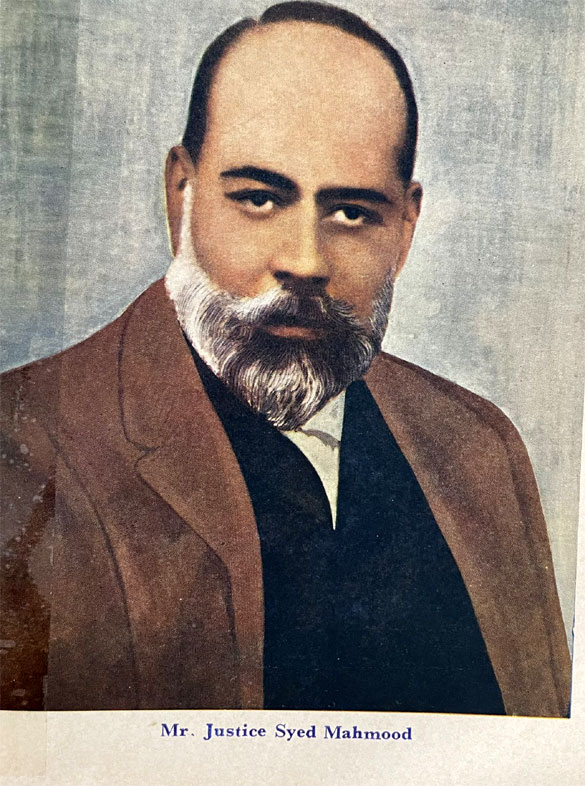

Justice

Syed Mahmood

----

Syed

Mahmood was born in Delhi in 1850 as the second son of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and

Parsa Begum. His experience of the horrors of the Mutiny of 1857 and the

ensuing Muslim pogrom inspired Syed Mahmood to plan for the future of Indian

Muslims till the end of his life. Seeing first-hand the course of a

generational change, Syed Mahmood also chose the searing path of Sir Syed, who

rejected the job guaranteed by the Mughal aristocracy and sided with the

British government, the masters of the new India. After his primary education,

Syed Mahmood joined Queen's College, Banaras in 1868, resigning from the

traditional way of learning.

In the same

year, Syed Mahmood, who passed the matriculation examination, was awarded a

scholarship given by the British government to the children of the elite class

of Indians. His son's life became a sacrifice for Sir Syed's thoughts to guide

the Muslims who were stuck in the time loop without being able to understand

the new changes to modernity through education.

In 1869,

Sir Syed along with Syed Mahmood went on a trip to England that decided the

fate of India. Although the trip was to enrol his son in Cambridge, it was

during this trip that Sir Syed became familiar with Western educational

methods. Syed Mahmood was also research assistant for Sir Syed's reply to

William Moore's ‘Life Of Muhammed’ written in London.

In 1870,

Syed Mahmood joined Christ's College under Cambridge for further studies. Syed

Mahmood became active in legal studies, listening to Charles Dickens, joining

Ananda Mohan Bose, and calling for equal citizenship for Indians. But the

father's dream was different. Sir Syed did not want to lavish his professional

career with personal gains, so he sent Syed Mahmood to study abroad. According

to David Lelyveld, Sir Syed's biographer, Syed Mahmood returned to India on 26

November 1872 due to his father's insistence. Even then, on 10 May 1869, he

joined the famous Lincoln's Inn in England as a barrister. Syed Mahmood

returned home and joined the Allahabad High Court as a barrister in 1872.

With

Father in Aligarh

During the

rebellion of 1857, Sir Syed was a clerk in the civil court (small causes court)

at Bijnur in present-day Uttar Pradesh. Later, he came to the North Indian

Muslims who were stunned to see their heritage and dynamism disintegrating

before their eyes, with the message of change. In 1863, Sir Syed started his

efforts by starting the Victoria College and Scientific Society. Muhammadan

Anglo-Oriental College was started in 1875 under the leadership of Sir Syed.

According to historian Sir Hamilton Gibb, the Muhammadan Oriental College was

the first modern educational institution in the Muslim world.

It was Syed

Mahmood's experience and foresight that guided his father's active hands. It

was Syed Mahmood who made Sir Syed tell before the Hunter Commission, which

came to study the state of education in India in 1882, "that the

Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College was intended to mould a number of people who

were Muslim believers, Indian by blood, and English by opinion." David

Leveld testifies to this.

During Sir

Syed's 17 months in England (1869-1870), it was Syed Mahmood who introduced him

to the modern methods of education in the West. At the age of twenty-two, he

prepared the Cambridge University Plan in Urdu and published it in the Aligarh

Institute Gazette. The document was a scheme of higher education on the model

of Cambridge University adapted to Indian conditions.

It was in accordance with this scheme that the

opening discussions of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College took place. It was

Syed Mahmood who wrote the constitution of 'Tarqiye Taalime Musalman'

organization formed by Sir Syed for educational activities on 26th December

1872.

On 8

January 1877, Viceroy Lord Lytton officially laid the foundation stone of the

Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College. In his speech at that event, Syed Mahmood

clearly stated the need and purpose of the college. “For the first time in the

history of Muhammadans (sic) the educational revolution was initiated by the

association of the community. Here is the beginning of a dream for a brighter

future, breaking the shackles of history.”

Syed

Mahmood had a close eye on all the affairs of the college. Syed Mahmood's

efforts were in designing, formulating the syllabus and conducting discussions.

Despite his busy life at the Allahabad High Court, he found time for college.

After resigning as a judge, Syed Mahmood's focus was entirely on the

development of the college. After taking leave in 1882, he went to England and

found and appointed Principal Theodore Beck, who later became the godfather in

the history of Aligarh.

The

Judge Who Placed Humanity over Colonial Justice

The High

Court Act of 1861 was a part of the reforms implemented after the Mutiny of

1857. High Courts were established in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay Presidencies

under Acts of the British Parliament. Allahabad High Court was established in

1866. In 1872, Syed Mahmood joined the Allahabad High Court Bar as the only

non-European barrister.

In 1876, at

the age of twenty-six, Syed Mahmood translated the Indian Evidence Act of 1872,

into Urdu. He entered the civil service in 1879 as a District Judge. This

appointment was due to the special interest of Viceroy Lytton. This appointment

is read as a reward for supporting progressive colonialism (Liberal

Imperialism). In 1881, on deputation, he assumed the position of adviser to the

Prime Minister of Hyderabad, Salar Jung.

Lal Rampal

Singh Case (Lal Rampal Singh Case) was a turning point in the life of Syed

Mahmood who returned to Raebareli in 1883. The case was about the power of the

mortgagor over the mortgaged property in case of default in repayment. The

Privy Council, the highest court of appeal in the colonial justice system,

upheld Syed Mahmood's verdict. Quoting verbatim from Syed Mahmood's judgment,

the Council praised his mastery of jurisprudence. The members of the Privy

Council referred Syed Mahmood to the High Court from the District Court. Things

became smooth when Viceroy Lord Ripon accepted the proposal. In 1882 Syed

Mahmood was promoted as Ad Hoc Judge in Allahabad High Court. He was appointed

as a temporary judge three times until his permanent appointment in 1887. On

May 9, 1887, Mahmood created history in the Indian judicial system with his

permanent appointment. Syed Mahmood was the first Muslim to be appointed as a

High Court judge in British India. He is also the first Indian Judge of

Allahabad High Court. In the history of the Indian subcontinent so far, Syed

Mahmood is also the youngest High Court judge. This appointment was the highest

honor an Indian could receive in the colonial justice system of that time.

In a racist

work environment, with justice and human rights above the letter of the law,

and through courageous interventions, Syed Mahmood continued until his

resignation in 1893 due to disagreements with the British Chief Justice.

The

judgment of Syed Mahmood who questioned the feasibility of British criminal law

in Queen Empress V. Phopi case is very important. Under section 423 of the

Criminal Code of 1891, even if an offender is unable to appear in court either

in person or through a lawyer, the trial judge's examination of the records of

the accused can be considered a 'hearing'. Syed Mahmood Ekanga strongly

disagreed with this. In his dissenting judgment, he stated: "The

examination of records by a judge cannot be considered a 'hearing' unless the

defendant or counsel is present in person." Citing this judgment, Justice

Krishnaiyar, hailed as the Indian father of public interest litigation, noted:

“This judgment was the first declaration of human rights at a time when justice

was the handmaiden of colonial interests. Instead of sacrificing justice to the

entanglements of law, he made humanity the cornerstone of the legal system

through this judgment.”

383 of his

important judgments have appeared in the Indian Law Report. Syed Mahmood's

refusal in the Queen Empress V Babulal case is still relevant. The “confession

procedure” was vague under the Indian Evidence Act of 1872. In this ruling,

Syed Mahmood overturned confessions obtained through torture. He added that

judicial members should be present for the confession of the accused in custody

to be accepted. Syed Mahmood became an unforgettable personality in the Indian

justice system because of this brave intervention. In the book 'Discordant

Notes', former Supreme Court Justice Rohindan Nariman has honored Syed Mahmood

as India's first exponent of the dissenting judgment.

Syed

Mahmood's knowledge of Muslim law was profound. He comprehensively dealt with

the problems during the gradual formation of Muslim personal law. Former

Supreme Court Chief Justice Hidayatullah had this to say about his

interventions in Muslim law. “He gave direction to the newly emerging Muslim

jurisprudence during the colonial period and tried to unite classical fiqh and

British common law on the same thread. He gave a precise shape to modern Muslim

jurisprudence by quoting from Fatawa al-Alamgiya, Hidayah and Roman Law.

His

judgment in the case of Amir Muhammed V. Jifro Begum marked a fundamental

reform in the law of distribution of inheritance in Hanafi fiqh. If a Muslim

dies in debt, the heirs are entitled to the property after the debt was

settled. This principle of Hindu joint family law was applicable to Muslims as

well. Syed Mahmood rewrote this law through his decree. His ruling was that

after death, the property should be distributed irrespective of the debts and

the heirs should pay the debts according to the share distributed. It was also

reminded that the distribution of Muslim inheritance should be done only

according to Muhammadan law.

His judgment in the case of Gobind Dayal V.

Inayatullah further clarified personal law in colonial India. The ruling was in

the case of "Shufa" (pre-emption) if two persons "A" and

"B" own land in a place and "A" sells the land to

"C" without mutual consent. He also commented on the scepticism in

colonial India about the applicability of Muslim law to non-Muslims. He ruled:

“For ages Muslim law was common law. Common law applies to everyone.

Non-Muslims saw common law as part of local customs. In the new changed

situation, Muslim law does not apply except between two Muslim persons as

British law is common law.”

In the case

of Shayara Bano V. Government of India, which considered triple talaq in 2017,

Supreme Court Judge Rohinran Nariman relied on this judgment of Syed Mahmood to

clarify the relationship between Muslims and personal law.

His

judgment in Jangu and Others V. Ahmed Ullah and Others case is interesting and

shows his knowledge of Muslim law. The case was about the right of a Muslim who

does not follow the Madhhab to say Ameen aloud among the Hanafi people who say

Ameen silently in prayer. He clarified that the church is a public place and

everyone has freedom of worship. He also stated in the judgment that the

ownership of the mosque belongs to Allah.

The

judgment in Abdul Kadir V. Salima case is still cited by courts today. The said

case is about the Muslim Marriage Act. The customs related to Muslim marriage,

the responsibility of the husband's mahr, the marital rights of the wife and

the husband, etc. were clearly explained in this ruling. He clarified that

Muslim marriage is not an indissoluble divine bond as in Hinduism, but only a

contract (Muslim marriage is not a sacrament but a contract). He explained that

Muslim marriage is only a civil contract based on classical texts. Mahr is the

right of the woman, after marriage the woman is not the husband's property but

the wife is only a party to a relationship that can be terminated easily were

other important parts of the verdict.

In the

Mazhar Ali V. Budh Singh Case, Syed Mahmood resolved the legal conflict between

the Indian Evidence Act and the Muslim Personal Law. Bengal Civil Courts Act of

1871 (Bengal Civil Court Act) gave effect to personal law for Muslims and

Hindus in matters related to inheritance, succession, marriage and caste. All

other civil matters were kept under British common law. According to the Indian

Evidence Act, 7 years of unrelated person will be treated as missing. According

to Hanafi fiqh, divorce can be granted if the husband has been absent for 99

years. In such a matter, the crux of the issue was whether a wife can declare

her husband, who has not been in contact with her for 7 years, as missing. His

ruling was that the disappearances were not to be tried under the Civil Courts

Act, 1871, according to Muslim jurisprudence. This ruling was based on

Istishab, one of the fundamental principles of Hanafi Fiqh.

In many

other judgments, Syed Mahmood's law was on the side of fairness and justice

without appeasing the colonial authorities. His judgments have been relied upon

by many courts of the world. Kenya, Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh and

Pakistan are just a few examples.

The end of

brave rebellious voices for justice was sad. Soon after his appointment, he

became increasingly estranged from Sir John Edge, the Chief Justice of the

Allahabad High Court. He did not tolerate Syed Mahmood, an Indian who raised

dissent against his rulings. Syed Mahmood resigned from the judiciary on 8th

September 1893. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, the father, was proud of his son who was not

ready to bend the law according to the whims of the British. A disagreement

with the Chief Justice led to his resignation, but his alcoholism, which by

then had become a ruin, was also the reason for his resignation. Drunkenness

was behind the downfall of the wise judge.

From

Judge to Legislator

After his

resignation, Syed Mahmood again engaged in the activities of Aligarh. In 1866,

he was active in the ``All India Muhammadan Educational Conference'' formed by

Sir Syed to discuss educational progress. At the request of the organization,

in 1893 and 1894 he researched contemporary Muslim education and presented a

report. 'A History of English Education in India: Rise, Development,

Progress and Present Condition of English Education in India with Special Reference

to the Muhammadans' was published as a book.

This report

was prepared by Syed Mahmood based on information collected from Hunter

Commission Report, various government documents, press releases, etc. It can be

considered as an introduction to the history of Indian Muslim education. Two

other books written by him in Urdu are 'Kitab Talaq' and 'Kitab

Shufa' (Book of Pre-emption). In 1896, Syed Mahmood returned to the Lucknow

court as a lawyer. He was nominated to the Oudh Legislative Council in January of

the same year. Records of his interventions in the Legislative Assembly are not

available today.

He spent

the rest of his life mainly in Aligarh, which he dreamed of with his father.

After his father's death, he was appointed secretary of the Muhammadan Oriental

College. But excessive drinking and the resulting attitude caused problems.

1899 He was removed from the post of Secretary and appointed as President. He

was removed from that post the following year. At the time of his death, he was

in the figurative capacity of Visitor of University.

He died on

8 May 1903 at the age of fifty-three. He rests close to his father's grave at

Mahmood Manzil, Aligarh. Syed Mahmood is a personality who brought many changes

in the field of education and the justice system in a very short time. He was a

judge who took justice as his master and constantly raised his rebellious voice

against the hypocrisies of the British legal system. And the intellectual power

of Aligarh Muslim University.

-----

A regular columnist for NewAgeIslam.com, Mubashir

V.P is a PhD scholar in Islamic Studies at Jamia Millia Islamia and freelance

journalist.

URL: https://newageislam.com/islamic-personalities/justice-syed-mahmood-colonial-/d/129777

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic

Website, African

Muslim News, Arab World

News, South Asia

News, Indian Muslim

News, World Muslim

News, Women in

Islam, Islamic

Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia

in America, Muslim Women

in West, Islam Women

and Feminism