The Unfortunate Princess – Beloved and Loyal Companion Of The Ill-Fated Prince Dara Shikoh

By Parvez Mahmood

24 Mar 2017

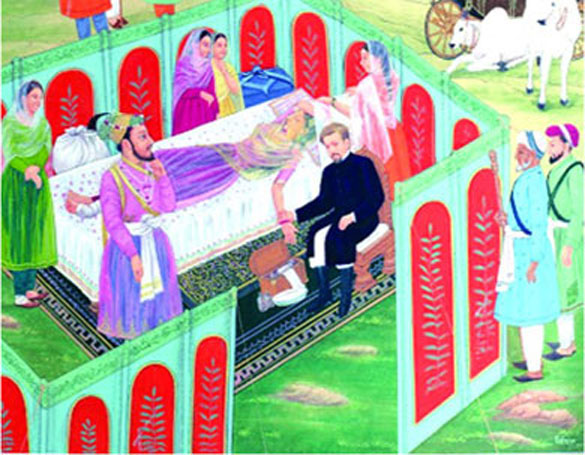

French physician Dr. Bernier examines a dying Nadira Banu as Dara,

defeated in battle, looks on anxiously

French physician Dr. Bernier examines a dying Nadira Banu as Dara,

defeated in battle, looks on anxiously

----------

The majesty of the Mughal Empire often conceals within its perplexing folds many a heartrending tale of profound tragedy and suffering. Such is the tale of Nadira Banu Begum.

She was the noblest of Mughal princesses, with the Emperor Akbar the Great as her paternal (as well as her maternal) great grandfather.

Her mother, Princess Iffat Jahan Begum, was a daughter of Emperor Akbar’s second son, Sultan Murad and his consort Salima Sultan Begum – whose own mother was a daughter of the founder of the dynasty, the Emperor Babur.

Her father was Sultan Muhammad Pervez Mirza – the second son of Emperor Jahangir – and his wife Sahib-i-Jamal Begum, a great granddaughter of Emperor Akbar’s wet nurse.

Dara, the heir apparent, was devoted to his wife and contrary to the practice of Mughal royals, he did not marry again

This noble lineage and unadulterated royal blood cast a curse that hounded her to a tragic death in a forlorn, deserted spot near the Bolan Pass (in modern-day Baluchistan) and a solitary burial in Lahore.

This Is The Story Of Her Tragic Life.

Her father Sultan Pervez Mirza remained loyal to his father during the filial rebellions, first by his elder brother Prince Sultan Khusrau and then by his younger brother Prince Khurram, the future Emperor Shahjahan. However, like many Mughal princes, he was ravaged by excessive drinking and opiate abuse, and died due to a head injury sustained in a drink-induced delirium at the young age of 38. By another account, he was poisoned by his younger step-brother, the ambitious and ruthless Prince Khurram who, having killed his eldest brother Prince Khusrau, wanted to clear the field for his own succession.

Nadira Begum was born in Merta, Rajputana, on the 14th of March 1618, and lost her father in 1622. She grew up in Agra and is reported to have been a person of some considerable charms – very intelligent and very beautiful.

She was engaged to Prince Dara Shikoh by his mother Empress Mumtaz Mahal. As the marriage was being arranged in 1631, the Empress died during the birth of her fourteenth child. Shah Jahan was devastated and stopped taking interest in matters of state. In the immediate aftermath of his bereavement, the Emperor was reportedly inconsolable and went into secluded mourning for a year. When he appeared again, his hair had turned white, his back was bent and his face worn.

His eldest daughter, Jahanara Begum, gradually brought him out of grief and took her mother’s place at court. One of the first joyous events that she arranged was the marriage of her brother Dara with Nadira. It appears she adored both of them. She wanted to celebrate their nuptials in style. Harbans Mukhia writes in his book Mughals of India: “Dara Shikoh’s marriage to Nadira Begum was a sort of landmark in extravagance even by Mughal standards. Jahanara was placed in charge of the wedding. Considerations of economy being alien to both her personality and her environment, she spent 1.6 million rupees (240 million in today’s money) on the festivities and gifts that were widely distributed among Princes, their sisters, wives and daughters of high nobles, and so on. The bride’s mother too spent 0.8 million rupees (120 million in today’s money) on her dowry.”

A magnificent contemporary painting, now hanging in the Brooklyn Museum in New York, depicts the marriage procession headed for the Emperor’s 40-pillared hall. There are numerous other paintings showing the various stages of the progress of the marriage.

Her death came at a merciful time, or else she would have had to endure the brutal murder of her son, grandsons and husband

Dara, the heir apparent, was devoted to his wife and contrary to the practice of Mughal royals, he did not marry again. They together had eight children, of which four died in infancy.

The Treasures Gallery of the British Library contains an album of paintings and calligraphy compiled by Dara Shikoh, which he gifted to Nadira Banu Begum in 1646-47. The album, containing 74 folios, has been described as one of the great treasures of the Asian and African department. It contains an inscription in the prince’s hand on folio 2, dated 1056/1646–47. The inscription records the gift of the album to his loving wife in the following words.

“In Muraqqa‘-I Nafis Ba-Anis-I Kha?? U Hamdam U Hamraz Ba-Ikhti?A? Nadirah Banu Begam Dadah [Shud Az] Mu?Ammad Dara Shikoh Ibn Shah Jahan Padshah-I Ghazi Sannah 1056

(‘This precious volume was given to his dearest intimate friend Nadira Banu Begum by Muhammad Dara Shikoh son of Shah Jahan emperor and victor, year 1056/1646–47’)

Nadira Banu Begum had a dreamy life as the consort of the heir apparent. But alas, it was not to last.

Shah Jahan fell sick and an inevitable war of succession commenced between his quarrelsome sons. Aurangzeb, the ablest general in the field and the most devious manipulator in diplomacy, emerged victorious. Dara was on the run and headed for Lahore. With their eldest son Sulaiman Shikoh in Kashmir as governor and unable to come to their help with his troops, Nadira Begum refused to leave the side of her husband in this time of misery and misfortune.

Dara, with his wife, reached Lahore to reorganise his army. A Rajput Raja Sarup Singh, whose territory was in northern Punjab near the mountains of Kashmir, came over with four thousand horse and ten thousand infantry and promised a further fifteen thousand cavalry and three hundred thousand infantry. Despite the promises of such unbelievable numbers, a desperate Dara believed him and begged him to come to his side. The Italian Niccolao Manucci in his famous account of the Mughal empire, Storia do Mogor, records that to secure the Raja’s loyalty to her husband’s cause, Nadira Banu Begum offered him water to drink with which she had washed her breasts (because she was not lactating) and called him her son. The Raja drank the water, swore allegiance and asked for money to pay his troops. Dara gave him one million rupees. Then the Raja promptly switched sides and never came to the aid of the Prince.

With Aurangzeb approaching fast, Dara wanted to escape to Kabul but found the route blocked. Instead, he marched with his family, including his wife, son Sipihr Shikoh and two grandsons – sons of Sulaiman Shikoh – towards Multan at the head of eight thousand troops. From Multan, the party went to the island fort of Bhakkar in the Indus River. On receipt of news of Aurangzeb’s approach, Dara marched again, leaving his grandsons with some of his trusted troops in the fort. Nadira again accompanied him to an uncertain future. He diverted to Thatta in November 1658, crossed the Runn of Kutch to go over to Gujarat and encamped in Ahmadabad. In the ensuing battle with Aurangzeb, Dara lost again. He backtracked through the Runn of Kutch and crossed the River Indus, attempting to go to Persia through the Bolan Pass.

This area was under the control of Jiwan Khan, a villainous chieftain, whose life Dara had once saved from the wrath of Shah Jahan. It was here that Nadira died under tragic circumstances. Dara himself was arrested by Jiwan Khan and delivered to Aurangzeb.

Dr. Bernier, a French physician attached to Dara, wrote a book on his travels in the Mughal Empire. He writes, “The Princess died of dysentery and vexation.” A painting in the earlier mentioned Dara Shikoh Album collection depicts Dr. Bernier examining the Princess with her worried husband looking on in a setting that clearly depicts Dara on the run.

Manucci – loyal to Dara till the very end – was at Bhakkar and resisted the siege till Dara with his fellow prisoners was brought there to ask his loyalists to surrender. He, therefore, must have been aware of the circumstances of the princess’s death. According to him, the “wife of Dara, finding herself in such a difficulty, along with her son Sipihr Shukoh, and her daughter Jani Begum, resolved to take her life with her own hands, so that she might not live to see her sons’ and her husband’s tragic and lamentable end.”

She is even quoted by Manucci as having said, “O beloved prince! O beloved sons! Now are your misfortunes at their height! Now has the hour come for your lives to end. With your blood the cruelty of Aurangzeb will be assuaged. Would to God that my life could suffice to quench the thirst of this ferret, or that with it I could restore yours, then would not Aurangzeb be so oppressive to you, nor so cruel to me! What could become of me after such a loss? Could I survive without sons, without a husband? Could I endure the deeper disgrace of becoming a concubine to Aurangzeb? God does not delight in this my evil state. But since there is now no other remedy, by taking my life I put an end to all my pains, and this tyrant gathers in by my death a portion of the spoils intended to grace his triumph.’

According to Manucci, “Speaking thus, she took the poison, which was so potent that as soon as she swallowed it, she fell dead.”

It is possible that both versions of her death are correct. She may have been weakened by dysentery when she took the poison to avert being captured by Jiwan Khan.

Her last wish was to be buried in Hindustan. Dara requested some of his loyal soldiers to carry her body to Lahore, for it to be buried near the tomb of Mian Mir – the saint who he so greatly venerated. His soldiers complied with his command but the circumstances of their travel are not known.

Her death came at a merciful time, or else she would have had to endure the brutal murder of her son Sulaiman and his two sons at Bhakkar fort, and then her husband Dara – whose head was severed and presented to Shah Jahan in his captivity by his son, the pious Aurangzeb.

The life of her younger son Sipihr was spared by Aurangzeb, whose daughter he later married. Her daughter Jani Begum was married to Azam Shah, the eldest son of Aurangzeb, who was later killed in the war of succession against his brother Bahadur Shah I, the seventh Mughal Emperor.

As for her fears that she might be taken as a concubine by the vengeful Aurangzeb, Nadira Banu Begum was not far from the truth, as the Emperor summoned both the surviving slave girls of Dara and made the Georgian slave girl Udaipuri Mahal his concubine. However, the Hindu slave girl, Ra’na-dil – who was previously a dancing girl – refused to appear before Aurangzeb and instead cut her hair and slashed her face to save her honour.

Princess Nadira’s mortal remains were brought to Lahore and buried adjacent to Mian Mir’s shrine in the middle of what has been reported to have been a large water tank at that time, but is a Char-Bagh turned playground now. A causeway stands from the eastern end of the ground to the tomb, which is in typical elegant Mughal style, with the cenotaph on a well-raised platform. There are signs – like the two rows of now non-functional fountains in red stone water channels – that the park has been renovated in the past. The crowded playground has been spared encroachment despite the rapid increase in population all around it. The tomb itself, however, is in an advanced state of decay and needs attention for cleanliness and preservation for future generations.

The Tomb Itself Is In an Advanced State Of Decay and Needs Attention for Preservation

During my last visit to the place earlier this year, I saw about a dozen different cricket teams playing in the grounds around the tomb. As I was taking a picture, my camera caught a hard-hit tennis ball flying inside the building and bouncing off the white marble grave – depriving the unfortunate Princess of the peace that she so desperately desired in her turbulent life.

Parvez Mahmood retired as a Group Captain from the Pakistan Air Force and is now a software engineer. He lives in Islamabad.

Source: thefridaytimes.com/tft/the-unfortunate-princess/

URL: https://www.newageislam.com/islam-women-feminism/the-unfortunate-princess-–-beloved/d/110541