On Takfīrī Extremism: Part 1 - Intellectual tools required to question Takfīrī Fatawas of South Asian Sectarian Ideologues

By Mohammad Ali, New Age Islam

Main points:

·

This essay

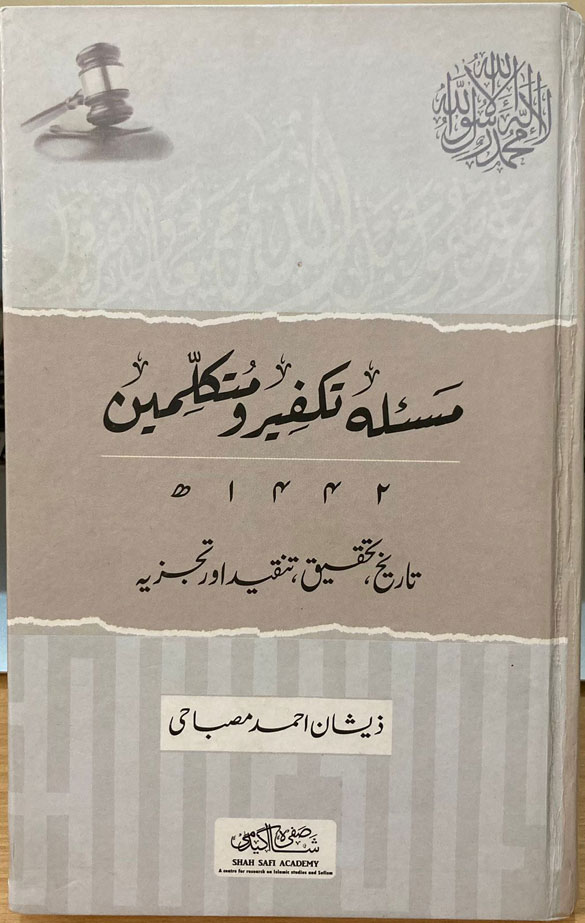

is the first in a series of articles discussing the contents of the book, Masla-e-Takfīr

wa Mutakallimīn: Tarīkh, Tahqīq, Tanqīd aur Tajziyya

·

This essay

highlights the historical and theoretical context of the takfīrī

extremism

·

It also

criticizes some of the views discussed in the book.

Fitna-e-takfīr denotes the

reckless and excessive use of the intellectual device of takfir to

anathematize a Muslim or a group of Muslims by an ‘ālim, a

theologian-jurist. Takfir or anathematization is a tool that can be

weaponized to instigate conflict and violence against non-Muslims as well as

Muslims. In theology, the use of takfir is supposed to protect the faith

from what is deemed to be destructive and dangerous ideas and interpretations

that threaten to distort the true meaning of revelation and undermine its

significance. However, in the medieval period, this theoretical tool was

politicized and used against political and religious adversaries, to justify

various actions ranging from social boycotts to violent conflicts against them.

The politicized version of takfir plays a significant role in conflict

within and beyond Muslim societies today. Therefore, to understand the recent and

ongoing conflict in the name of Islam, one needs to unravel the fundamental

theological assumptions first that have been distorted to justify the social

and political violence. The best way to refute the takfīrīextremism is

to depoliticize the concept of takfir by understanding it in its

theoretical and theological framework. In a series of essays (this one is the

first of them), I would like to discuss the principles of takfir

according to the theologians and explore a new discourse based on theological

tolerance in Islamic tradition.

Several events can be recounted that

have been termed fitna-e-takfīr in Muslim history, beginning with the

emergence of Kharijites in the first century of Islam. They deemed Muslims

other than themselves as kāfir. The same events spiraled again during

the time of Ghazali who had to demarcate the boundaries of kufr and īmān:

what meant to be a Muslim or a kāfir, in one of his seminal works,

Faysal al-TafriqabaynalIslāmwa al-Zandaqa. Despite several warnings of

caution against calling a Muslim a kāfir in Islamic scriptures, a number

of Muslim scholars succumbed to their prejudices and negligence and unleashed

this fitna numerous times. Issuing takfir against fellow Muslims

excessively is a tendency that is caused by convincing himself of the

superiority of his own theological opinions to his adversaries' understanding

of the Islamic scriptures. Ghazali viewed people who act out such tendencies as

heretics. Sherman Jackson, while commenting on Ghazali’s arguments offered in Faysal,

writes,

Several events can be recounted that

have been termed fitna-e-takfīr in Muslim history, beginning with the

emergence of Kharijites in the first century of Islam. They deemed Muslims

other than themselves as kāfir. The same events spiraled again during

the time of Ghazali who had to demarcate the boundaries of kufr and īmān:

what meant to be a Muslim or a kāfir, in one of his seminal works,

Faysal al-TafriqabaynalIslāmwa al-Zandaqa. Despite several warnings of

caution against calling a Muslim a kāfir in Islamic scriptures, a number

of Muslim scholars succumbed to their prejudices and negligence and unleashed

this fitna numerous times. Issuing takfir against fellow Muslims

excessively is a tendency that is caused by convincing himself of the

superiority of his own theological opinions to his adversaries' understanding

of the Islamic scriptures. Ghazali viewed people who act out such tendencies as

heretics. Sherman Jackson, while commenting on Ghazali’s arguments offered in Faysal,

writes,

“Heretics are often just as strident

in their judgments, just as swift in calling for sanctions against their

adversaries, and even more convinced of the superiority of their own

theological views.” (On the Boundaries of Theological Tolerance in Islam, P.4.)

The recent events of fitna-e-takfīr

originated in colonial India during the early nineteenth century and

proliferated after that in the forms of schools of thought (known as maslak,

pl. masālik): Deobandi, Barelvi, and Ahl-e-Hadith. These groups have

doctrinal differences and on the bases of them accuse each other of blasphemy

or/and innovation. A close look at the works of the leaders of these schools

reveals that they fit in the category of what Ghazali termed as ‘heretics.’ No

serious scholarly attention has been paid to understanding the approaches of

these scholars and unearthing their underlying presuppositions. However,

recently, a scholar, Zeeshan Ahmad Misbahi, felt the need to explore Ghazalian

thoughts on the issue and tried to rekindle the discourse on takfīrī

tendency among ‘ulamā and Muslims today, in his book, Masla-e-TakfīrwaMutakallimīn:

Tarīkh, Tahqīq, Tanqīd aur Tajziyya. He wrote this book in Urdu and

examined the principles of engaging with the issue of takfir in

light of the writings of classical Muslim scholars. Even though he is not

expressive in stating what a reader will get from his book, this book intends

to provide its readers with the intellectual tools that can enable him/her to

judge the demand of a maslak that its followers must declare a Muslim

from another maslak a kāfir.

Due to the importance of the book, I

intend to discuss the contents of Misbahi’s book in a series of essays. It will

benefit those who neither read Urdu nor have access to the technicalities of

this complex subject.

With regard to the issue of takfir,

there have been two traditions in Islam, one is followed by mutakallimīn

(plural for mutakallim, who engages in speculative theology), and the

other is followed by fuqaha, jurists. The latter approach is not as

complex as the former one. I will try to discuss these two approaches later in

detail. Misbahi thinks that mutakallimīn are more cautious in issuing a fatwa

of takfīr than the jurists. Therefore, as the word, mutakallimīn,

in the title of the book suggests, he believes that if the approach of mutakallmīn

is employed sectarian bigotry among the Muslim community can be reduced.

In the introduction to the book,

Misbahi outlines the preliminary characteristics of the current takfīrī

tendencies as well as the concerns that motivated him to write the book. The

foremost reason that has been strengthening the takfīrī culture among

Muslims in South Asia is the existence of the modern maslaks. These maslaks

were established in the colonial period and persist today. As pointed out

earlier, each maslak demands complete obedience to the theology

propounded by its leaders, plus imprecation or anathematization of the people

(Muslims) associated with other maslaks. Misbahi thinks that the

existence of these maslaks feeds into the growth of takfīrīextremism.

How did these maslaks survive and become so powerful? Misbahi responds

to this question by arguing that it became possible due to the absence of a

‘grand leadership,’ meaning a global, or at least, national leadership,

possessing the power to censor the heretic views and prevent them from

spreading.

This instance of lamenting for the

socio-political and religious decline of Muslims because of the absence of a

political and religious authority one finds in Misbahi’s book is not rare among

traditional Islamic scholars. I found one such example in Fazl-e-Rasūl

Badauni’s book, Saif al-Jabbār, a polemic, which he wrote around 1853

against Shah Ismail’s interpretations of Islamic creeds. This argument can hold

some value, but it ignores the historical fact, meaning, such takfīrī

extremism have had emerged during the time of the Muslim caliphate and sultans.

It is also premised on the old assumption that the caliphate or a

religiopolitical authority could protect the Muslim world from disintegration.

I believe that the takfīrī extremism is the result of a simple and

atomistic reading of the religious texts and believing that only one

interpretation can be true. It has also resulted from the blind following of

what has been said in theological matters refusing to allow any fresh inquiry

into the interpretations that have already been propounded by maslak

leaders. For example, Barelvis do not allow fresh thinking into some issues

that are fundamental to their maslak and have been interpreted by

Ahmad Raza Khan. The same is true in other South Asian maslaks as

well. In order to counter ideological extremism, one needs to devise an

intellectual response as did Ghazali in his time. Thinking about the need for a

political authority, whether it is a caliphate or some other form of power,

that could repel the heretical tendencies among Muslim societies can have some

serious repercussions. A political authority can sensor some heretical

claims, but investing such power in it in modern times will be tantamount

to allowing the persecution of intellectual freedom.

Misbahi argues that ‘ulamā in

general have become a part of this takfīrī industry. When he says ‘ulamā

in general, I believe, he is talking about the ‘ulamā who are associated

with a maslak and belong to South Asia or the South Asian diaspora in

the world. Because it would be absurd to believe that all ‘ulamā in the

world have been indoctrinated into this extremism. Many ‘ulamā in other

parts of the world do not condone the practice of anathematizing Muslims

without any valid and explicit proof. Misbahi asserts that the maslakī‘ulamā

are unaware of the harm they are doing to the Muslim community. Their takfīrī

extremism and mutual ideological conflicts are not only obscuring the image of

Islam, but they are also making the lives of Muslims difficult. In the presence

of these maslaks, when everyone is anathematizing the other, Misbahi

argues, it becomes impossible to conceptualize an ummah, a global Muslim

faith community.

…..........

Mohammad Ali has been a madrasa student. He has also

participated in a three years program of the "Madrasa Discourses,” a

program for madrasa graduates initiated by the University of Notre Dame, USA.

Currently, he is a PhD Scholar at the Department of Islamic Studies, Jamia

Millia Islamia, New Delhi. His areas of interest include Muslim intellectual

history, Muslim philosophy, Ilm-al-Kalam, Muslim sectarian conflicts, madrasa

discourses.

------------

URL:

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism