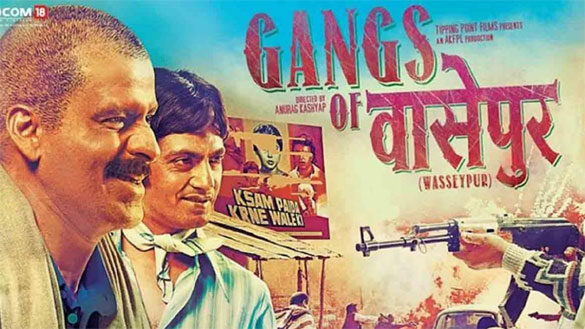

Gangs of Wasseypur: Wild West Comes To Bihar

By Saif Shahin, New Age Islam

Ek bagal mein khankhanati seepiyan ho jayengi

Ek bagal mein kuch rulati siskiyan ho jayengi

Hum seepiyon mein bhar ke saare taare chhoo ke aayenge

Aur siskiyon ko gudgudi kar ke yoon behlayenge

(I will have shells jingling on one side

And sobs on the other, making me cry

We’ll fill up the shells, go touch the stars and return

And tickle the sobs to make them dry)

While growing up in the northern plains of Bihar, I loved watching Spaghetti Westerns―all the way from John Wayne to Clint Eastwood. There was something so outlandish about them that despite their breathless guns and bloodletting, I found them rather amusing. Little did I then know that if I wanted to see the Wild West for myself, I had only to look a few miles to my south―towards the coal mines around the charred, soot-soaked town of Dhanbad.

My neighbourhood Wild West complete with its dust-laden rusticity and bloodthirsty brawn, comes to life in ‘Gangs of Wasseypur’. The film is an epic retelling of the vicious circle of violence that has gripped Dhanbad and its vicinity from before Independence, weaving together political history and social commentary with sweat-scented tension and a wry humour. The first part of the five-hour drama was released on 22 June, the second part is due to be released in August.

The story, based on actual news reports, is a multi-generational account of the blood feud between two Muslim families―one Pathan and the other Qureshi (butcher)―and how it is used by a powerful Hindu Bhumihar for political gains. Protagonist Sardar Khan has vowed to avenge his father’s murder at the behest of mining contractor-turned-minister Ramadhir Singh.

Sardar’s father Shahid Khan was himself a ‘bahubali’ (local strongman) working for Singh in the village of Wasseypur, but was murdered when Singh learnt of his plan to betray him. Singh also sent Ehsaan Qureshi, another bahubali, to murder the kid Sardar Khan, but Sardar was saved by his uncle. And there is historic bad blood between the Khans and the Qureshis: an ancestor of the Khans had once been kicked out of the village by a Qureshi.

While Sardar Khan’s return and rise to strength in Wasseypur, his attempts to humiliate and destroy Singh and Singh’s manipulation of the Qureshis to strike back forms the plot, the film is mainly about relationships―communal, casteist, sexual and interpersonal―and the role of power. The Khan and the Qureshi communities live on different streets of the village. Although both are Muslim and pray at the same mosque, there is no love lost between them.

The Qureshis are dominant, and all other Muslims are afraid of them. The dichotomy has little to do with religion, sect, ideology or beliefs. It’s rooted in local history and is all the more real for it, surviving colonial rule, Independence, Emergency, the transfer of mining rights from the British to local contractors and back to the government, even the death of illegal mining as a lucrative business. Governments, politics and economics change, but the social fracture remains.

And while there is such a deep divide among Muslims, there is no apparent Hindu-Muslim fissure. Ramadhir Singh initially uses a Qureshi as a bahubali, then turns to Shahid Khan, and again to a Qureshi. While he uses the social divide for political gains, he has no personal misgivings against Muslims in general―inviting the Qureshis home for lunch (his wife suggests they use their special china set on the table).

The depiction of gender relations is perhaps the most powerful. Sardar Khan uses Islamic precepts to justify his womanising ways―telling his uncle that Allah must have had a reason to “want” men to take four wives, and men like his uncle were being selfish by not heeding to it. But women, while resigned to their secondary status in this rigidly patriarchal society, are complex characters in their own right. Naghma, Sardar’s tough-talking first wife, is ready to kill him when she finds him at a brothel, but herself later tells him to “go out for fun” when she is pregnant, even flippantly rebuking him for not eating enough to sustain his virility and leaving himself susceptible to mockery.

The film is as incisive as Sardar’s blade, and as fluid as the blood on its tip. The plot resembles Alexander Dumas’s ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’, its multi-generational trajectory has a hint of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, while the style and tenor of filmmaking are redolent of Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino. And yet, rustic Bihar oozes out of every scene―in the sing-song way in which the characters talk, the bowl-cut hairstyles of the older generation and the garish, over-the-top dressing sense of the later ones, but perhaps most of all in the unremarkable, almost unnoticeable manner in which life comes and goes, is given and taken away.

Saif Shahin is a research scholar at the University of Texas at Austin. He writes regularly for New Age Islam.

URL: https://newageislam.com/islam-sectarianism/gangs-wasseypur-wild-west-comes/d/7802