The Critical Friend: Ambedkar’s Mirror and The Crisis of Indian Islam

By V.A. Mohamad Ashrof, New Age Islam

12 December 2025

This paper is a radical re-evaluation of the intellectual relationship between Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891-1956) —the principal architect of the Indian Constitution—and the Islamic tradition. While Ambedkar is globally celebrated for his annihilation of Brahmanical orthodoxy, his engagement with the sociology of Indian Muslims remains a contested and uncomfortable terrain. This paper posits a provocative thesis: that Ambedkar’s scathing critique of the Muslim community, articulated primarily in his 1940 treatise Pakistan or the Partition of India, should not be viewed as an adversary’s polemic, but as a "critical friend’s" diagnosis. When synthesized with the humanistic hermeneutics of contemporary Islamic liberation theologians, Ambedkar’s voice becomes a catalyst for a profound Muslim Renaissance (Tajdid) grounded in the Quranic imperatives of Justice (Adl) and Egalitarianism (Musawah).

The Sociological Gaze and Theological Possibility

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar occupies a unique space in the phenomenology of religion in South Asia. As a scholar who converted to Buddhism to escape the suffocating hierarchy of caste Hinduism, his approach to religion was fundamentally utilitarian and ethical. He measured the worth of a faith not by its metaphysical claims, but by its sociological output: Did it produce liberty, equality, and fraternity? It is through this lens of "Constitutional Morality" that Ambedkar turned his gaze toward the Indian Muslim community during the tumultuous decade preceding the Partition of 1947.

Conventionally, Ambedkar’s observations are utilized by majoritarian forces to paint him as anti-Muslim. However, a rigorous academic reading reveals that Ambedkar applied the same "hermeneutics of suspicion"—a method of interpretation that unmasks hidden repressions—to Islam as he did to Hinduism. He was not attacking the theology of the Quran per se, but rather the "sociological betrayal" of that theology by the Muslim feudal and clerical elite.

To construct this argument, this paper places Ambedkar’s sociological critiques in conversation with the intellectual giants of contemporary Islamic thought, such as Farid Esack, and Asghar Ali Engineer. This synthesis is necessary because Ambedkar identifies the symptom (social stagnation), while Islamic Liberation Theology identifies the cure (a return to Ijtihad and Quranic universalism).

The "Corporation" of Islam: Ambedkar’s Diagnosis

The first and perhaps most philosophically damaging critique Ambedkar levelled against the Indian Muslim community concerns the nature of their social solidarity. In a passage that has reverberated through decades of political discourse, Ambedkar analysed the concept of Islamic Brotherhood. He acknowledged that Islam possesses a potent binding force, capable of uniting diverse ethnicities. However, he questioned the scope of this brotherhood.

"The brotherhood of Islam is not the universal brotherhood of man. It is brotherhood of Muslims for Muslims only. There is a fraternity, but its benefit is confined to those within that corporation. For those who are outside the corporation, there is nothing but contempt and enmity." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 340).

This critique strikes at the heart of democratic pluralism. Ambedkar argued that if a community’s ethical obligations are strictly internal—limited to the Ummah—then that community cannot truly participate in a secular, democratic nation-state which requires a "universal civil fraternity." He feared that this "Insular Brotherhood" created a psychological ghetto, where the Muslim allegiance to the faith superseded their allegiance to humanity.

Sociologically, Ambedkar was observing the political dynamics of the 1940s, where the Muslim League was utilizing religious identity to carve out a separate political existence. He saw a community turning inward, fortifying its boundaries against the "Other." He described this as a "closed corporation," a term evoking exclusion and privilege rather than spiritual openness.

It is crucial to concede the sociological validity of Ambedkar’s observation within its specific historical context. The political theology of the pre-Partition era was indeed characterized by a binary worldview—Dar al-Islam (Abode of Peace) versus Dar al-Harb (Abode of War). However, to accept Ambedkar’s diagnosis as the final word on Islamic theology would be an academic error. While Ambedkar accurately described the behaviour of the community, he did not engage deeply with the scripture that ostensibly guided them. Herein lies the opportunity for a "Muslim Renaissance."

A "hermeneutical reading" of the Quran offers a powerful counter-narrative to the idea of the "closed corporation." The Quranic concept of community is not static or exclusive; it is ethical and universal.

Islamic feminist scholar Amina Wadud argues for a "Tawhidic paradigm" of social justice. Tawhid (the Oneness of God) implies the unity of all creation. Contrary to Ambedkar’s fear of a brotherhood limited to "the corporation," the Quran explicitly situates the Muslim community (Ummah) as a servant to all of humanity:

"You are the best community evolved for mankind (li-n-nas); enjoining what is right and forbidding what is wrong" (Q.3:110).

The preposition li-n-nas (for the people/mankind) is critical. It signifies that the Ummah does not exist for itself, but for the benefit of the universal human family. Furthermore, the Quranic ethos of engagement is enshrined in the verse on human diversity:

"O mankind! We created you from a single (pair) of a male and a female, and made you into nations and tribes, that you may know one another (li-ta'aruf)" (Q.49:13).

Asghar Ali Engineer interprets ta'aruf (mutual recognition) as the antithesis of the "contempt and enmity" Ambedkar described. The purpose of difference is dialogue, not the erection of a "closed corporation."

Ambedkar’s critique acts as a "warner." By exposing the ugliness of "Insular Brotherhood," Ambedkar challenges the contemporary Muslim to reject tribalism. The path to a Muslim Renaissance lies in dismantling the "corporation" and replacing it with a "Universal Civil Society," fulfilling the constitutional morality Ambedkar envisioned.

Theological Crisis of Exclusivism and the Quranic Mandate for Pluralism

In the architecture of Ambedkar’s critique, the second pillar is the diagnosis of Religious Exclusivism. If the first critique dealt with the sociological boundaries (who belongs?), the second critique interrogates the epistemological arrogance (who holds the truth?). Ambedkar viewed the democratic project as a "mode of associated living" characterized by mutual respect. He feared that a community convinced of its sole possession of the Truth would find it theologically impossible to treat "Others" as equals.

Ambedkar articulated this anxiety with surgical precision:

"Islam can never allow a true Muslim to adopt India as his motherland and regard a Hindu as his kith and kin... The allegiance of a Muslim does not rest on his domicile in the country which is his but on the faith to which he belongs." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 340).

While often cited to question Muslim patriotism, a deeper reading reveals Ambedkar’s concern with Supersessionism—the doctrine that one’s faith has invalidated all previous truths. Ambedkar reasoned that if a community believes it holds the "Final Word," it inevitably views other communities as errors to be corrected or conquered. This "logic of monopoly" creates a psychological barrier to egalitarianism.

Ambedkar’s observation was rooted in the 1940s context dominated by the "Two-Nation Theory." The political theology of the era relied on a binary jurisdiction. Ambedkar rightly identified that this binary worldview is incompatible with a secular democracy. In a democracy, there is no Dar al-Harb (Abode of War); there is only the Civitas, the shared civic space. By critiquing this exclusivism, Ambedkar was essentially asking: Can a Muslim be a citizen of the world, or only a citizen of the Ummah?

To respond to Ambedkar, we turn to the hermeneutics of scholars like Abdulaziz Sachedina (1942-2025). The "Muslim Enlightenment" hinges on recovering the Quranic validation of the "Other." Ambedkar’s premise was that Islam claims to be the only true path. However, the Quran complicates this claim in Q.5:48:

"To each among you, We have prescribed a law and an open way. If God had so willed, He would have made you a single people, but (His plan is) to test you in what He has given you: so strive as in a race in all virtues (fastabiqu al-khayrat)."

Sachedina argues that this verse asserts that religious diversity is the Divine Will. God intended for there to be multiple paths. If we apply this to Ambedkar’s critique, the argument of "exclusivism" collapses scripturally. The Quran does not demand a monolithic world; it demands "Competitive Righteousness."

A crucial hermeneutical tool for dismantling religious exclusivism is the classical but often forgotten distinction between Din (the universal essence of faith) and Shariah (context-bound legal and ritual pathways). Progressive Muslim scholars argue that Din represents humanity’s universal orientation toward the Absolute, rooted in justice, compassion, human dignity, and truth — values shared across all spiritual traditions. The Quranic affirmation that “the same Din has He established for you as that which He enjoined on Noah…” (42:13) underscores that divine purpose is singular, whereas legal expressions inevitably differ. Modern maqaṣid theorists emphasize that the Shariah must be understood as a dynamic, purpose-driven path rather than a fixed set of historical rules, and that its higher objectives—protection of life, dignity, intellect, faith, and socio-economic justice—belong to all humanity, not to any exclusive community.

From this angle, Ambedkar’s critique becomes strikingly relevant. What he encountered in colonial India was not Islam as a universal Din but a Muslim public sphere preoccupied with Shariah as an identity boundary—ritual conformity, communal separatism, and political exceptionalism such as the demand for separate electorates. Ambedkar lamented that ethical universals were overshadowed by the anxieties of preserving difference. Progressive Muslim scholars agree that when Shariah is reduced to identity markers and political mobilization, its deeper objectives—justice, equality, and moral uplift—are lost. Khaled Abou El Fadl repeatedly insist that divine law must serve moral meaning, not communal superiority, and that any legal formulation contradicting human dignity or justice cannot claim divine legitimacy.

A Muslim Renaissance thus requires a reordering of priorities: Shariah understood as historically shaped, plural, and reformable must be placed in service of the universal Din whose essence is shared ethical humanity. This shift aligns with modern maqaṣid frameworks that call for cross-religious cooperation in preserving human welfare, justice, and dignity. Recognizing that other traditions also pursue the same higher objectives allows Muslims to affirm their identity without denying the spiritual or ethical validity of others. In this vision, the richness of Muslim identity is celebrated precisely by transcending exclusivism and aligning the Shariah with its original purpose: to cultivate a just, compassionate, and inclusive world in harmony with the divine moral order that binds all of humanity.

Ambedkar’s anxiety about the Dar al-Harb mentality can be addressed by retrieving the concept of Dar al-Ahd (Abode of Covenant). Tariq Ramadan argues that the binary of "Islam vs. War" is a medieval construct. He proposes the concept of Dar al-Shahada (Abode of Witness), where Muslims live in diverse societies to "bear witness" to ethical values. The Constitution of India, in Islamic terms, is a Mithaq (Solemn Covenant) similar to the Constitution of Medina.

The Soteriological Crisis — Who is Saved?

Central to the "Anti-Pluralist Worldview" is Soteriology (the doctrine of salvation). Ambedkar felt that a "Union of Spirits" was impossible between a "saved" Muslim and a "damned" Hindu. However, the Quran delivers a rebuke to the idea of a "Salvation Monopoly":

"Those who believe (in the Quran), and those who follow the Jewish (scriptures), and the Christians... any who believe in God and the Last Day, and work righteousness, shall have their reward with their Lord." (Quran 2:62).

Scholars like Khaled Abou El Fadl emphasize that this verse creates a "theology of promise" extending beyond the institutional Muslim community. Salvation is contingent on Iman (faith) and Amal Saleh (righteous deeds), not on tribal affiliation.

Ambedkar’s critique touches upon authority. Who speaks for God? El Fadl distinguishes between the Authoritative (the text) and the Authoritarian (the human interpreter). Because humans are finite, no human interpretation can capture the totality of Divine Intent. This creates space for "Epistemological Modesty." If Muslims accept Ambedkar’s critique, they must admit that the "brotherhood" practiced in South Asia has often been exclusionary. The solution is not to abandon Islam, but to reclaim the Quranic universalism that predates the calcification of the "corporation."

"Frozen in Feudalism"

In the anatomy of Ambedkar’s sociological critique, the third observation is the Resistance to Reform. Ambedkar turned his gaze toward the temporal dynamism—or lack thereof—within the Muslim body politic. Writing in the 1940s, he observed the secularization of Turkey under Atatürk. Yet, in India, he saw a depressing contrast.

Ambedkar remarked: "The Muslims have no interest in politics as such. Their predominant interest is religion... The Muslim politicians do not recognize secular categories of life as the basis of their politics because to them it means the weakening of the bond of Islam." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 350).

He lamented the "absence of the desire for change," noting that while Turks had abolished the Caliphate, Indian Muslims were fighting to preserve it (the Khilafat Movement). Ambedkar saw this as a symptom of deep-seated intellectual ossification, describing the community as "frozen in feudalism."

Ambedkar offered a psycho-sociological explanation for this stagnation. He argued that the "Minority Complex" paralyzed the Indian Muslim intellect. Living alongside a vast Hindu majority, the fear of "submergence" led to reactionary conservatism.

"The existence of these evils is a distressful fact. But the situation is rendered much more distressful by the fact that there is no organized movement of social reform among the Musalmans of India on a scale sufficient to bring about their eradication." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 233).

He reasoned that any attempt at internal reform was viewed as a "weakening of the fortress." Thus, the "will to reform" was sacrificed at the altar of "communal unity."

Ambedkar’s diagnosis of the Indian Muslim condition was sociologically accurate, but his implication that Islam itself is inherently resistant to change requires correction. The Quran is replete with concepts mandating dynamism: Tajdid (Renewal) and Islah (Reform). The Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said that God will send a renewer (Mujaddid) to the community every century. Islah is the mission of all prophets to "heal" the earth (Quran 11:88).

To answer Ambedkar’s charge, we must employ the distinction between Thawabit (Constants) and Mutaghayyirat (Variables). The Thawabit are the immutable principles of faith (Tawhid, Justice). The Mutaghayyirat are social transactions subject to time. Ambedkar observed a community that had elevated Mutaghayyirat (medieval dress, feudal laws) to the status of Thawabit. A Muslim Renaissance demands the "desacralization" of history.

The mechanism of the stagnation Ambedkar observed is Taqlid (Blind Imitation). The Ulama relied on memorizing medieval rulings without questioning their context. Ambedkar wrote:

"It is a system of social and political life which is static and not dynamic... It is this which makes the Muslim such a difficult problem." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 352).

The antidote to Taqlid is Ijtihad—independent reasoning. Fazlur Rahman proposed a "Double Movement" theory: 1) Go back to the Quranic context to extract the moral principle; 2) Return to the present to apply that principle. If we apply this to Ambedkar’s critiques (e.g., caste or democracy), the result is transformative. The "stagnation" Ambedkar saw was a colonial and feudal construct, not a Quranic necessity.

To understand the "inertia," we must analyse the historical trauma of 1857. The collapse of the Mughal Empire shattered the Muslim psyche. In response, the community bifurcated: The Aligarh Movement (Western education but socially conservative) and the Deoband Movement (inward-looking orthodoxy). Ambedkar encountered the community when this defensive insularity had coalesced into a "separatist psycho-social formation."

Ambedkar argued that isolation would not save the Muslims; it would rot them.

"A community which feels that it is a ruling community... needs no reform. But a community which feels that it is a subject community... clings to its past as the only source of its inspiration." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 232).

He was diagnosing a collective narcissism born of defeat. By critiquing this, Ambedkar was acting as a "Critical Friend," arguing that one cannot build a future by hugging the corpse of the past.

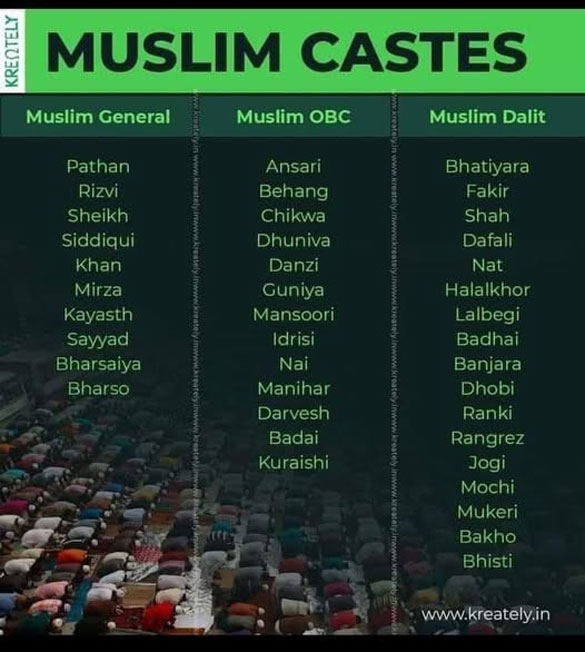

The Anatomy of Muslim Caste: Ashraf, Ajlaf, Arzal

In the annals of sociology, few observations have been as provocative as Ambedkar’s diagnosis of caste among Muslims. Having critiqued insularity and stagnation, Ambedkar turned to the most sensitive nerve: Caste. He refused to accept the theological claim—that Islam has no caste—as a sociological fact.

His conclusion was blistering:

"The Muslims have all the social evils of the Hindus and something more. That something more is the compulsory system of purdah for Muslim women... [But regarding caste] take the caste system... Islam speaks of brotherhood. Everybody infers that Islam must be free from slavery and caste... But if slavery has gone, caste among Musalmans has remained." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 228-230).

This assertion—that Muslims possess the evils of Hindus "and something more"—challenges the self-image of the South Asian Muslim. How does one explain that the "liberators" became enslaved?

Ambedkar utilized Census data to map the hierarchy:

1. Ashraf (The Noble): Foreign descent (Syeds, Pathans) or upper-caste converts. They monopolized power.

2. Ajlaf (The Commoners): Indigenous converts from artisan castes (Weavers, Butchers).

3. Arzal (The Degraded): Converts from "Untouchable" castes.

Ambedkar cited the Census regarding the Arzal:

"With them the other Mahomedans will not associate, and they are forbidden to enter the mosque or to use the public burial ground." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 231).

This exposes the "Great Contradiction." While the Muezzin calls the faithful to prayer with the promise of equality, the social structure enforces segregation based on birth (Nasab).

Decades later, the Pasmanda Movement (Dalit/Backward Muslims) has validated Ambedkar’s critique. Scholars like Anand Teltumbde argue that Ambedkar serves as a natural ally for the Pasmanda struggle. Ambedkar saw that the "Muslim League politics" of the 1940s was essentially "Ashraf politics"—a demand by the landed gentry to secure feudal privileges.

Ambedkar was sensitive to the plight of the "Dalit Muslims" (Arzal). He observed that conversion did not emancipate the Untouchable; it merely changed his label.

"The Mahomedan has no caste... This is the common view... But the fact is that caste survives conversion... The Arzal is the equivalent of the Hindu untouchable." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 230).

This demands that the community acknowledge it has failed its most vulnerable. The Renaissance cannot be built on the backs of the Arzal.

How did the Ulama justify caste? They utilized the concept of Kafa'a (compatibility in marriage). In India, the Ashraf Ulama interpreted Kafa'a strictly through Nasab (lineage) and Pesha (occupation), issuing Fatwas declaring that a Syed cannot marry a Julaha (weaver).

Ambedkar noted:

"There can be no inter-marriage between the different castes of Muslims... The Ashraf considers it below his dignity to marry into the Ajlaf." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 230).

To counter this, the Muslim Enlightenment must centre the Prophet’s Farewell Sermon: "An Arab has no superiority over a non-Arab... except by piety." This is the "Constitutional Morality" of Islam. Ambedkar’s critique validates the Pasmanda demand for a "Casteless Islam" in practice, not just theory.

The Gendered Critique and the Horizon of a Civilizational Alliance

We arrive at Ambedkar’s most visceral critique: the status of women. While his other critiques were political, this was deeply humanistic. He described Purdah (seclusion) not as a custom but as a pathology.

"They [Muslim women] are usually the victims of anaemia, tuberculosis, and pyorrhoea... The physical degeneration of Muslim women is not the only evil result of the Purdah. It is responsible for a spiritual atrophy among the Muslim women and a moral degeneration among the Muslim men." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 231-232).

Ambedkar argued that by locking half the community behind the Zenana, the community was engaging in self-sabotage. For Ambedkar, citizenship was corporeal and intellectual; Purdah was the negation of citizenship.

Uniquely, Ambedkar analysed the effect on men, arguing that Purdah led to "moral degeneration" by depriving men of healthy social contact with women.

"Purdah deprives the Muslim men of some of the most disciplinary influences of society... It stimulates men's sexual desire to an unnatural degree... and establishes a separate sex culture." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 232).

He saw the "segregated society" as incompatible with the "democratic society."

Ambedkar noted that while Hindu women also suffered, the Muslim community seemed to double down on seclusion as an identity marker.

"The Muslims have all the social evils of the Hindus and something more. That something more is the compulsory system of purdah... The Muslims are the only people who have established a system of imprisoning their women." (Ambedkar, BAWS Vol. 8, p. 230).

The key word is Compulsory. Ambedkar inverted the community's metric: true enlightenment is measured by liberty, not seclusion.

The Islamic Feminist response—championed by Amina Wadud and Fatima Mernissi—validates Ambedkar’s sociological observation while refuting the theological justification. They argue that the Purdah Ambedkar saw was a cultural accretion. Wadud argues that the domination of women (patriarchy) violates Tawhid. If a man claims authority over a woman’s agency, he usurps God’s authority.

Mernissi engages in historical analysis, pointing out that the "Hijab" of the Quran was not a universal command for the segregation of all women. She argues that the "imprisonment" Ambedkar critiqued was a later invention of the Abbasid elite. The most powerful Quranic refutation is Q.9:71, which describes believing men and women as Awliya (protective friends/allies) of one another. You cannot be an "ally" to someone you have imprisoned.

Ambedkar lamented the lack of female political leadership. However, the Quran offers the archetype of the Queen of Sheba (Bilqis), a democratic leader who consults her council and reasons her way to Truth. She provides the theological basis for the political agency Ambedkar found missing.

The prophet said: “By God, the time is near when a woman will travel from Sanaa to Hadramawt fearing none except God” (Bukhari 3595). This celebrated prophecy, spoken in a tribal environment marked by endemic violence, signals nothing less than the Prophet’s vision of a socio-moral transformation in which women become full beneficiaries of public safety, mobility, and dignity. Islamic feminist scholars highlight that the hadith reframes security not as a male-guardianship prerogative but as a universal right grounded in justice and social reform. The Prophet ties women’s freedom of movement to the ethical success of the community, implying that the measure of an Islamic society is the extent to which women can travel, work, learn, and participate in public life without fear. Far from restricting women, this hadith dismantles patriarchal assumptions that female mobility must be controlled, asserting instead that a truly God-conscious society ensures structural conditions—rule of law, social equality, economic fairness, and moral accountability—where women’s autonomy is normalized. In this vision, women’s safety and mobility become prophetic indicators of a just Islamic civilization, aligning directly with modern Islamic feminist claims for gender-equal citizenship.

Toward a Civilizational Alliance

We have traversed the five pillars of Ambedkar’s critique:

1. Insular Brotherhood: Answered by Quranic Universalism.

2. Religious Exclusivism: Answered by Quranic Pluralism (Fastabiqu al-khayrat).

3. Stagnation: Answered by Ijtihad.

4. Caste: Answered by the Prophetic abolition of lineage pride.

5. Patriarchy: Answered by Musawah and Awliya.

Ambedkar acts as a mirror in which the community can see its own scars. He is a "Critical Friend" in the Socratic tradition. As Anand Teltumbde notes, "Ambedkar’s criticism of Muslims was not to condemn them but to provoke them to reform."

The conclusion posits that the future of Indian secularism depends on a "Civilizational Alliance" between the Ambedkarite (Dalit/Bahujan) movement and the Muslim community. This cannot be a mere electoral arithmetic; it must be an Ethical Alliance. A casteist, patriarchal Muslim community cannot be a true ally to an egalitarian Ambedkarite movement.

We propose a new vocabulary for this alliance: Adl (Justice) meets Samata (Equality); Ukhuwwah (Brotherhood) meets Maitri (Loving-Kindness). Seventy-five years later, the "frozen" ice is melting. The rise of Pasmanda and Feminist voices proves the "desire for change" has arrived. To engage Ambedkar is to step into the light of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity—which is, ultimately, the Light of God (Nur Allah).

Bibliography

Ambedkar, B.R. Pakistan or the Partition of India. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, Vol. 8. Mumbai: Government of Maharashtra, 1990.

Rahman, Fazlur. Islam and Modernity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Teltumbde, Anand. Ambedkar on Muslims. New Delhi: Vikalp Publishing, 2003.

Wadud, Amina. Quran and Woman. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

….

(V.A. Mohamad Ashrof is an independent Indian scholar specializing in Islamic humanism. With a deep commitment to advancing Quranic hermeneutics that prioritize human well-being, peace, and progress, his work aims to foster a just society, encourage critical thinking, and promote inclusive discourse and peaceful coexistence. He is dedicated to creating pathways for meaningful social change and intellectual growth through his scholarship.)

URL: https://www.newageislam.com/islam-politics/ambedkar-indian-islam-crisis/d/137979

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism