Madhumalati by Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan: A Fusion of Hindu and Sufi Mysticism in Mughal-Era Literature

By Syed Amjad Hussain, New Age Islam

6 December 2024

Madhumalati, Written By Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari In 1545, Blends Hindu And Sufi Mysticism, Depicting A Love Story That Symbolizes The Soul’s Journey Toward Divine Union. It Highlights The Syncretic Religious Culture Of Mughal India, Illustrating A Harmonious Fusion Of Spiritual Beliefs Beyond Boundaries.

Main Points:

1. Madhumalati is a mix of Hindu and Sufi mysticism, in which love is a journey to the spiritual.

2. The poem is reflective of the syncretic religious culture of Mughal India, which symbolises Hindu-Muslim coexistence.

3. Manjan's philosophy of life has love, knowledge, and yoga intertwined.

4. The story is about divine love and unity beyond religions.

5. Madhumalati gives insight into the spiritual and cultural context of the Mughal period.

-----

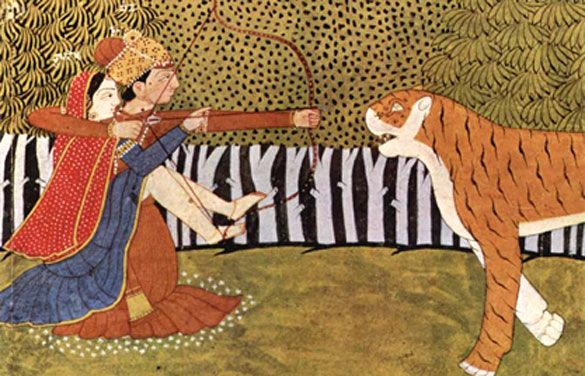

Lovers shoot at a tiger in the jungle. Illustration to the mystical Sufi text Madhumalati.

------

Teaching South Asia in the contemporary geopolitical world is challenging, and themes like religion and communalism are thorny issues. Teaching Hindu-Muslim relations in South Asia, especially in introductory courses about the region or world history, becomes increasingly challenging as students enter with preconceived notions based on assumptions about religion in the modern world. One of the strongest lessons presented through these discussions is that the contemporary constructs of religion cannot be placed upon historical antecedents. By taking this subtle step through the study of historical texts, students learn how the very concepts of religion and identity were fluidly multifaceted in the premodern world.

Madhumalati by Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Danishmand Shattari Rajgiri is one of the great case studies for such discussions. Penned in 1545, this epic poem yields a remarkable window into the syncretic religious world of medieval India, where Hinduism and Islam were not distinct and opposed but intertwined in a shared cultural and spiritual landscape.

Historical Context of the Mughal Empire and Its Religious Landscape

The Mughal Empire was an age of intense religious interaction and, at times, tension between 1526 and 1707. Self-consciously Muslim rulers ruled over a largely Hindu population. The empire attempted to consolidate diverse Indian traditions into a unified political structure often by the accommodation of Hindu religious practice and governance alongside Islamic norms. This accommodation is often overlooked or politically contested in the modern India story, which often depicts Mughal rule as a period of Muslim over Hindu oppression. However, as Madhumalati’s life story so well illustrates, the Mughal period was not characterised solely by religious conflict. The Mughal emperors, especially under emperor Akbar, endorsed a pluralistic approach to governance, which enacted and incorporated elements of both Hindu and Muslim cultures. Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari’s poetry is a good example of syncretism taking place in the Indian subcontinent during this period.

Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari: A Syncretic Poet in the Mughal World

Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari was a Sufi poet and spiritual head of the Shattari order in India. Being a member of a well-known family of scholars and mystics, his spiritual lineage could be traced to Hazrat Meer Syed Imad-ud-Din Hasni al-Baghdadi, whose family was believed to have relations with the sacred house of Hazrat Imam Hasan, the grandson of Prophet Hazrat Muhammad Sallallahu Alayhi Ta’ala Wasallam.

Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari was born to Hazrat Meer Syed Muhammad 'Syed Jeev' Danishmand. His father, Hazrat Syed Jeev belonged to the family of Hazrat Meer Syed Imad-ud-Din Hasni from Baghdad, one of the most renowned Sufi saints. Hazrat Syed Jeev gave the first serious spiritual training to Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari, whose idiom and poetry would contain an esoteric amalgamation of ideas pertaining to Islamic mysticism as well as Hindu philosophical tendencies.

Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari’s wife was the daughter of Hazrat Shaykh Qazin Shattari, who was a principal leader in the Sufi Shattari order. In fact, he became a significant figure in the Shattari spiritual and intellectual traditions through his marriage to Hazrat Bibi Khadija Dawlat, daughter of Hazrat Shaykh Qazin Shattari. Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari was known to master religious and worldly sciences along with Arabic, Persian, and Hindavi-the old Hindi or Urdu. His works in the tongue of Hindavi such as Madhumalati remain as a unique thread that interweaves threads both of Hindu and Islamic strands.

Madhumalati: The Religious Syncretic Masterpiece

Madhumalati is an epic poem. It is based on the love story of the protagonist Manohar, a prince, and his beloved Madhumalati. It was written in 1545 CE. Being only romantic about the passion of love, it is an allegory concerning the Sufi journey unto union with the Divine; both Islamic and Hindu traditions regarding mysticism are drawn upon during these same poetic lines, blending elements into syncretism characteristic within that Mughal age, religiously speaking. For instance, he introduces his book with God Allah in Islam, but employs the Hindu Om as a totem to signify divine power. He also invokes the concept of the Hindu cosmological notion of Three worlds and Four yugas (ages of time) that becomes critical to Hindu metaphysical thought. Therefore, he has created a new religious vocabulary transcending the traditional limitations of both faiths.

Throughout the poem, these references to the gods Indra and Hanuman merge with the central Islamic motifs of divine love and mystical longing. The commingling of the two religious traditions is not juxtaposition between two systems of beliefs; it shows synthesis, which brings to us what historians refer to as Indo-Islamic culture, a tradition where Islamic faith was indigenised and integrated with the local cultural practices and beliefs.

It had set up less than half a century with its authority in India at the time of Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari writing Madhumalati. Periodic tensions between a Hindu majority and Muslim rulers made life under orthodox rulers like Aurangzeb Alamgir anything but smooth within the Mughals, but their system of governance was fairly accommodating in ways. Religions across the board were integrated under Akbar, much like the Din-e-Ilahi he started—a syncretic religion that was based upon elements of both Hinduism and Islam.

Syncretic attitudes toward religions and governments can also be found in writers such as Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari, whose Madhumalati underscores the profoundly interwoven nature of Hindu and Muslim spiritual practices in Mughal India. It is time to highlight in the classrooms today how these assumptions are quite wrong since religious conflict in this region has always been perceived as eternal and essential to the experience of South Asia. This assumption goes contrary to Madhumalati, which combines several aspects of both Hinduism and Islam to offer a far more nuanced, historically informed understanding of religious interaction in pre-modern India.

Conclusion: Religious Syncretism during the Mughal Period

Hazrat Meer Syed Ali Manjan Shattari’s Madhumalati is an invaluable source for understanding the religious and cultural dynamics of Mughal India; at the same time, it is evidence of the Indo-Islamic tradition that sprouted with the coming of the Mughal rulers, representing an art where the policies of religious accommodation culminated in the culture and literature of the time. This is an important reminder for modern students about the dynamic character of religious identifications and practices shaped by historical, political, and social forces. Madhumalati, with its tapestry of ideas on Hinduism and Islam, would have a very appealing story of syncretism challenging modern compartmentalised views of religion.

Further Insights into Madhumalati’s Depiction of Divine Love

According to Sufi tradition, the same Madhumalati expresses, this whole world is bound up in a mysterious Premasutra (thread of love) that if followed, will lead the seeker to the Premamurti (the embodiment of divine love). Sufis, being bewitched by the hidden light of the divine in all its forms, become possessed by the 'Prem-Rasaladen' (the essence of love's nectar). Describing the vast and unique form-beauty of Madhumalati, Manjan says:

"Know it when you see it. That's the way it is;

Printing is the same. This is the same form of creation.

You can sew the same look. Live in the same way.

The same form appeared in many ways. This is how the world is."

In these lines, Manjan invokes God in the Samasokti method and offers a compelling and vivid depiction of the incomparable beauty of God, the eternal source of all beauty, under the guise of Madhumalati’s form-beauty. A beautiful thing, according to this perspective, is eternal and joyful. The lines indicate God's vast form-beauty permeating nature and suggest that the Parasrup (divine form), which Jaisi has imagined, is similarly invoked by Manjan in these lines.

God, as per these teachings, is omnipresent, Yatra-Tatra (everywhere), existing in various forms in every particle of creation. The unique aura of the Lord's form-beauty constantly appears in the three worlds from the particles of nature.

God's love and the love of passion are at the core of the Sufi path. Unless these are there, one cannot tread on the Sadhana path, nor can anyone's eyes open up. Manjan then discusses the concept of divine separation amidst so much transience of beauty in the world:

"It is immeasurable the time.

Why would the world come to an end? This creation is a time immemorial".

Nain Birah Anjan Jin Sara.

Birh Roop Darpan Samsara.

Koti Mahin rare world. I was really sad.

This world, in its pure aspect, becomes a clean mirror to him whose heart retains within it the divine separation, a sense of God in His forms. Once that transmutation has taken place, all the forms of creation speak the same truth; and one realizes finally, this ultimate unity of all.

Madhumalati on the Portrayal of Divine Love

It was composed in 952 Hijri, which is 1545 AD. The poem tells the beautiful love story of Manohar, the son of King Surajbhan of Kanakagiri Nagar, and Madhumalati, the daughter of King Vikramaraya of Maharas Nagar. As mentioned earlier, the poem depicts the king of all rasas, or shringar rasas, as per the Kavisvekarokti tradition, wherein love, knowledge, and yoga are the foundational elements of existence. What, in particular, is innovative and unique to Manjan lies in the integration of this knowledge-yoga with love, so inextricably woven into his poetic text.

No other Hindi Sufi poet has so perfectly and miraculously euphemised love as Manjan has done. He has elegantly proposed the omnipresence of God under the cloak of the form-beauty of Madhumalati. Sufism, in its philosophy, has been so potently placed within the text of Madhumalati that even an allegorical love affair, in a way, narrates the main spiritual concept of Sufism.

More than an act of poetic love affair, Manjan presents philosophy that gives the readers greater insight into divine love and union. The love saga of Manohar and Madhumalati reflects the strong metaphor used as a pathway for a journey in the Sufi way. The soul tends to reach out in communion and union with the Divinity, free from human selfish desires and passions. Manjan's presentation of love as a spiritual power that can lead the lover towards enlightenment is a powerful expression of the Sufi way.

Madhumalati is not just a lovely romantic story but also a spiritual allegory, which represents the vision of the world and the beauty of the divine of the Sufis. The love story of Manohar and Madhumalati, set against the backdrop of a world filled with physical and spiritual longing, offers a glimpse into the infinite love of God, which transcends all earthly boundaries. The work illustrates the fluidity and interconnection of religious thought during the medieval period, where Hindu and Muslim traditions coexisted and intertwined to form a syncretic cultural and spiritual experience.

Blending elements of Hindu and Sufi traditions, Madhumalati not only shares an ageless love tale but also a powerful religious message of unity and peace about how the divine is to be understood and experienced in multilateral ways across different cultural and religious boundaries. This timeless text is a testament to the power of love and devotion as pathways to understanding the divine, offering profound insights into the spiritual and cultural milieu of Mughal-era India.

Ultimately, Madhumalati reminds us that love—whether it is romantic, divine, or spiritual—is a powerful force that transcends all boundaries, leading the soul towards unity with the Divine. In the South Asian literary traditions, Madhumalati is an important reminder of the interweaving of Hindu and Muslim cultural and spiritual practices and hints at a time in Indian history when things were far more harmonious and inclusive, where syncretism of religious and cultural aspects was not only possible but was also celebrated.

In conclusion, Madhumalati is an extraordinary piece of literature in which the religious and cultural syncretism that was characteristic of the Mughal period in India shines through. Through its blend of Sufi and Hindu motifs, it is a valuable insight into the spiritual and cultural landscape at the time, offering a message of divine love and unity that transcends time.

-----

Syed Amjad Hussain is an author and Independent research scholar on Sufism and Islam. He is currently working on his book 'Bihar Aur Sufivad', based on the history of Sufism in Bihar.

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism