Nath Sampraday and Muslims: Prior To the 20th Century, the Nath Community Spoke To A Muslim Audience and Opted To Acquire Power through Religious Inclusivity

By Christine

Marrewa-Karwoski

23/MAR/2018

These last

few weeks have been arduous for Uttar Pradesh’s chief minister Adityanath.

Crisscrossing India, this mahant of the Gorakhnath temple in Gorakhpur has been

using his spiritual standing to garner votes for BJP candidates from Tripura to

Karnataka. While it is by no means unusual for Nath yogis to involve themselves

in political matters, the manner in which Adityanath is using right-wing Hindu

rhetoric to woo voters defies the more traditional tenets of his faith.

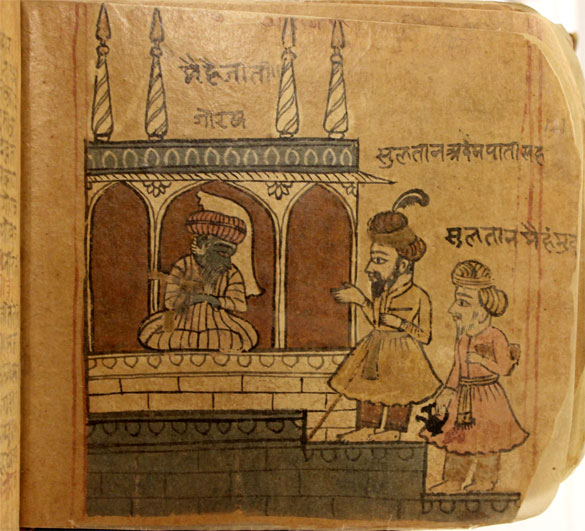

Rare illustrations from 1715CE Nath manuscript located

at the Wellcome Collection, London (ccby4).

----

Two

recently rediscovered and never before printed Nath teachings, the Avali Silūk

and the Kāfir Bodh, illustrate in detail that although Adityanath polarises

communities in order to gain political influence, prior to the 20th century,

members of the Nath Sampraday opted to acquire power through religious

inclusivity.

The Curious Case of the Missing Teachings

In 1942,

shortly before his untimely death, Pitamber Dutt (P.D.) Barthwal constructed

something that hadn’t previously existed: a stable and authoritative written

text containing the Hindavi teachings of the Nath yogis. Entitled the

Gorakhbānī, this seminal work on the Nath Sampraday was based on a wide range

of manuscripts and constituted a critical edition of the teachings attributed

to Gorakhnath and other yogis.

And while

Barthwal, unfortunately, passed away before the first publication of his book,

this edition of the Gorakhbānī has

maintained its position as the cornerstone for a modern understanding of Nath

ideology for over 80 years. Yet, what if we were to find that teachings

imperative to understanding the complexity of this community had somehow been

omitted from the book Barthwal had intended to produce? This question is

essential to consider, since, as it turns out, this is indeed the case.

A

particularly strange discrepancy arises when carefully examining Barthwal’s

Gorakhbānī, the product of his extensive research. Close inspection of his book

reveals that at some point before the publication, two important teachings had

been erased from the modern Nath canon. The intriguingly named Avali Silūk (The

Highest Song) and the Kāfir Bodh (The Knowledge of the Unbelievers), while

discussed in Barthwal’s introduction, fail to have been included in the

compilation that Barthwal had so painstakingly prepared. While it is virtually

impossible to know if these texts were intentionally removed by disapproving

editors or if they were mistakenly omitted due to Barthwal’s sudden death;

however, clearly their disappearance has significantly affected the way in

which the modern world views the Nath yogis.

The “Muslim” Texts

The Avali

Silūk and the Kāfir Bodh make their first appearance in the earliest extant

Hindavi writings attributed to members of the Nāth yogis (a 1614CE manuscript

currently housed in the Sri Sanjay Sharma Museum and Research Institute in

Jaipur) and continue to circulate in various manuscript traditions well into

the 19th century.

These

fascinating teachings are often placed alongside one another as if they are

meant to be working in tandem. And even though they are significantly different

in style, the intended audience of their teachings is undoubtedly Muslim. The

two teachings demonstrate that the Nath yogis not only preached acceptance of

Islamic beliefs and the continuation of Muslim obligatory practices but also

had a desire to present their faith to Muslim communities as a continuation of

Islam.

It was

these two teachings that prompted Barthwal to write that the Avali Silūk and

Kāfir Bodh “…press[ed] home to him that both the Hindus and the Mohammedans

were servants of the Lord, emphasising at the same time that the Yogis made no

distinction between the two and thus were not partial to any of them.”

However

paradoxical it may seem, the sampradāy wished to assert their identity as

accepted extensions of both these communities and as transcending all other

worldly religious practices. For the Naths, straddling somewhat contradictory

roles and identities was not a problem to be resolved, but a mentality to be

embraced.

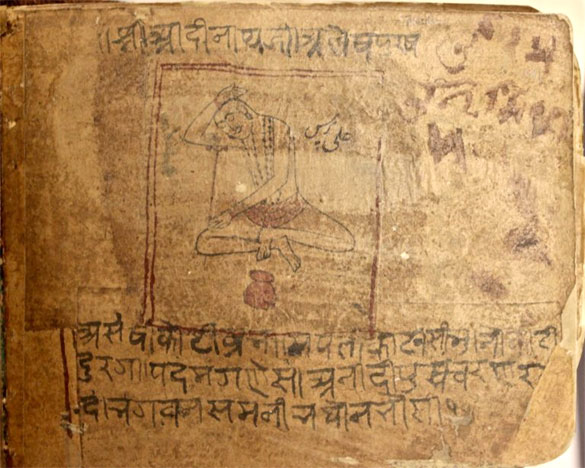

Rare illustrations from 1715CE Nath manuscript located

at the Wellcome Collection, London (ccby4).

-------

Nath

teachings, including the Avali Silūk and the Kāfir Bodh, urged their audiences

to think beyond duality and to find comfort in that which was necessarily

uncomfortable. In the early-modern period when competitions for spiritual

superiority were common in order to attract followers and gain patronage, this

philosophy had great pragmatic value as well. Instead of alienating either

Hindu or Muslim rulers, Nath yogis sought to include both religious traditions

into their fold and hoped to be seen as members of both of these communities.

And they accomplished this. Mughal emperors and Hindu kings alike often

patronised them and sometimes became devotees of specific Nath teachers or

different temple complexes.

The

placement of the Avali Silūk as the first of the Muslim Nath text in the

manuscripts invited devotees to enter a sacred space within the Nath community

in which Islamic beliefs could not only co-exist with Hindu ones but were also

welcome to retain their Islamic specificity. This is obvious from the style of

the text. Whereas other teachings of the Nath community are most often composed

in a linguistically simple Hindavi, often referred to as Sadhhukkaṛī (or language of the sants), much

of the Avali Silūk is communicated in a highly Persianised and Islamicised

vocabulary, asserting to its audience – in terms they could clearly understand

– how the Nath community embraced Islamic beliefs, rituals and practitioners.

UN Rights

Chief Expresses Concern on FCRA Law, India Says Expects 'More Informed View'

Although

embedded within a Hindu framework through the invocation of the sacred

syllable, Aum, and ending with an emphasis on the transcendence of spiritual

duality (and the yogic asanas needed to overcome this duality), the majority of

the Avali Silūk references terms that are specifically Islamic.

That the

Avali Silūk both praises Muslim ideals and builds inroads to mutual

understanding between Islam and Nathism can be observed even within the very

first verses of the teachings.

Himati Kateb Hasya/ Behimati Beketeb Hasya/

Kibar Dusman Hasya/ Bekibar Dosasī Hasya/

Gusa Harām Hasya/ Hak Halāl Hasya/

Naphase Saitān Hasya/ Benaphas Dilpāk Hasya/

Gumān Kāphir Hasya/ Begumān Avaliyā Hasya/

[Courageous

are those of the book, those who do not follow the book are cowards. The

haughty man is the adversary; the one with humility is the friend.

Anger is haram, truth is halal.

The one who desires is the devil, the one who

is satisfied is pure of heart.

The man with ego is the infidel; humble is the

Muslim holy man.]

And yet,

perhaps more interesting is the manner in which the Avali Silūk includes Muslim

beliefs and rituals. The following passage not only appears to demonstrate how

Islamic practices can be yoked with Nathism, but it also recognises the

importance of these rituals and sacred spaces.

Jān Masīti Hasya/ Bejān Bemasīti Hasya

Dil Miharāb Hasya/ Bedil Bemiharāb Hasya

Svāphī Ujū Hasya/ Besvāphī Beuju Hasya

Kalamā Kabūl Hasya/ Bekalama Nākabūl Hasya

Nekī Bekhat Hasya/ Badī Nabakhat Hasya

Dilak Musalā Hasya/ Besidak Nāmusalā Hasya

Mihari Nivāj Hasya/ Bemihari Nānīvāj Hasya

Saram Sūnati Hasya/ Besaram Nāmasaru Hasya

Sīl Rojā Hasya/ Besīl Nārojā Hasya

[Life is

the masjid, without life there is no place of worship. The heart is the mihrab,

without it one does not know the direction in which to pray. The Sufi is the

wudu, without him you can not prepare yourself for prayer. Kalima is

acceptance, without the profession of only one God and Mohammad as his prophet,

there is no acceptance. Goodness is good fortune, wickedness is bad

fortune. Sincerity is the Musallā,

without sincerity there is no place to pray to God. Compassion is namaz,

without it there is no prayer. Modesty is sunnat, without it there is no

Islamic custom. Good character is your Roza, without good character there is no

fast or show of self-restraint.]

The second

text, the Kāfir Bodh, also speaks to a Muslim audience concerning the

transcendence of religious duality, though its approach is different. In

contrast with the Avali Silūk, which largely maintains a studied Islamicised

tone that would have felt welcoming in its linguistic register and religious

overtones, the Kāfir Bodh begins in a more defensive manner beginning with

Gorakhnath asking, “Kauṇas Kāfir/ Kauṇ Murdār/ Doi Svāl Kā Karau Bicār/ Hame Nakāfir/ Amhe Fakīr.” [Who is an

infidel and who is dead (leaving the world of illusion behind)? Reflect on

these two questions. We are not Kafir! We are Fakīr].

Yet after

this brief antagonistic beginning, the tone of the teaching softens and

describes the self-conception of the Naths in terms of attributes they believe

qualify them for the status of fakīrs. While both texts are attempts to

spiritually transcend religious divisions, the Kāfir Bodh endeavours to do this

through challenging pre-conceived notions about Nath yogis within different Muslim

communities and speaks without hesitation of their spiritual superiority over

both Hindus and Muslims.

Ham Jogī Na Rākhai Kisahī Ke Chaṃde

Anant Mūrtti/ Anant Chāyā

Agam Agocar Yū Raū Bhāyā

Dev Na Deūrā /Masīt Na Munārā

Śrab Niraṃtar Kaṃkar

[We yogis don’t

care for what are other peoples verses of praise. There are limitless idols and

limitless protection. Thus we are pleased with that which is in accessible and

imperceivable. There are neither Devas nor temples, neither masjid or minarets.

All are just the same stone.]

As the

teaching continues, it reinforces that neither Hindus nor Muslims can fully

encompass Nath ideology, the foundation of which is the total acceptance of

paradox; the ability to surpass duality. The early-modern Nath community may be

welcoming to both religions, however, ultimately both fall spiritually short of

the true understanding which only the Nath teachings can provide.

Conclusion

While today

Adityanath, the most recognisable face of the sampradāy, uses his clout to

occlude the diverse history of the Nath yogis, the political shift towards the

Hinduisation of the Nath sampradāy is very much a 20th century construct.

Although Nath yogis had been involved in politics for centuries, it was only

under the direction of Mahant Digvijay Nath (c.1934-69) that the Gorakhpur

Temple Complex began to turn violently away from its inclusive political past.

Although

colonialism, modernity and a newly ascendant Hindu majoritarianism all deeply

affected the manner in which different Nath communities articulated their

identities and sought to maintain their political influence, it was Digvijay

Nath’s leadership in Gorakhpur which laid the groundwork for Adityanath’s

communalist agenda.

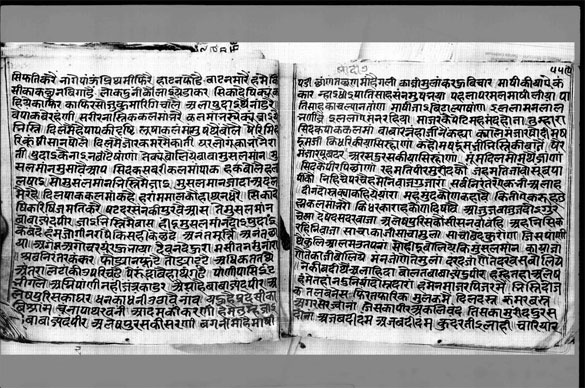

The 1614CE manuscript housed at Sri Sanjay Sharma

Museum and Research Institute in Jaipur, Rajasthan.

-----

Digvijay

Nath’s dedication to Hindutva ideology far outweighed any enthusiasm he may

have had for Nath spiritual practices. In fact, according to George Weston

Briggs’ account of the Gorakhpur Nath temple during the 1920s, prior to even

becoming an initiated yogi, Digvijay Nath was involved in a lawsuit in which he

hoped to gain leadership over the Nath temple complex. He had promised that if

he were to win the Gaddī he would become a member of the Sampraday and have his

ears split (the traditional initiation for Nath yogis).

He did

eventually win his lawsuit, have his ears split, and become mahant of the

temple. However, it is clear from the beginning of Digvijay Nath’s leadership

that he wished to use his influence in a different, less spiritual manner. It

is in these political footsteps that Adityanath follows.

Although

further study is necessary to understand the full import and circulation of the

early- modern Nath texts throughout South Asia, the re-discovery of these

teachings is critical evidence for how the early-modern Nath community

envisioned its place within both Muslim and Hindu communities. Re-establishing

their place in the literary canon is a necessary step toward understanding the

fullest expressions of the Nath tradition. At a time when members of the BJP

and Adityanath, in particular, claim to be concerned with exposing distortions

made to Indian history, perhaps it is fitting to suggest that as the mahant of

the Gorakhpur Nath temple complex, Yogi examine the texts and history of his

own community first.

-----

C. Marrewa Karwoski, a former Fulbright Fellow,

is in her final year of a doctoral programme at Columbia University in the City

of New York. She specialises in Hindi literature and religious politics in

North India.

Original Headline: The Erased 'Muslim' Texts of

the Nath Sampradāy

Source: The Wire

URL: hhttps://www.newageislam.com/interfaith-dialogue/nath-sampraday-muslims-prior-20th/d/123218

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African

Muslim News, Arab

World News, South

Asia News, Indian

Muslim News, World

Muslim News, Women

in Islam, Islamic

Feminism, Arab

Women, Women

In Arab, Islamophobia

in America, Muslim

Women in West, Islam

Women and Feminism