Investigating The Interplay Between Education, Modernity, And Social Reform In Sir Syed’s Intellectual Framework: A Critical Analysis With Reference To Tehzib ul Akhlaq

By

Dr. Javed Akhatar, New Age Islam

18 July

2023

Introduction

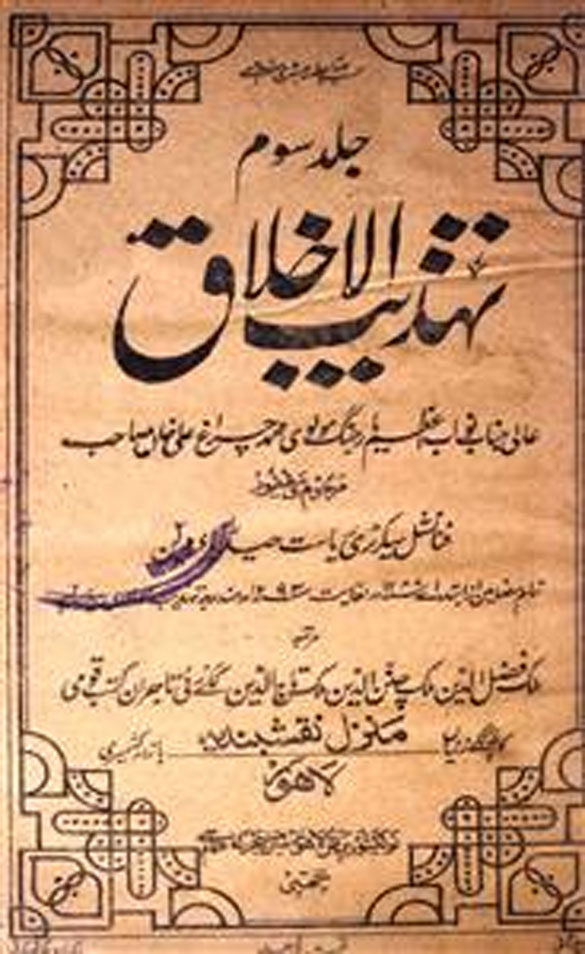

Sir Syed

Ahmad Khan, a prominent figure in the early stages of the reform and

modernization movement within the Indian Muslim society, played a pivotal role

in introducing progressive ideas to his fellow Muslims. Among his notable endeavours

was the establishment of a journal called “Tehzib-ul Akhlaq” in 1870 A.D.,

which served as a responsible and influential platform for driving societal

change. During his visit to England, Sir Syed became acquainted with two

popular periodicals, namely “Tatler” and “Spectator,” which inspired him to

create an Indian journal aimed at combating bigotry, superstitions, prejudice,

and ignorance prevalent among Indian Muslims. Expressing his aspirations to

Mohsin-ul Mulk while in England, Sir Syed wrote, “I have decided to launch a

journal dedicated solely to the betterment of Muslims. It will be called

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq in Persian and Mohammedan Social Reformer in English.”

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq covered a wide range of topics, including religious and literary

subjects, focusing on matters related to reform, science, and the intellectual

and educational upliftment of Indian Muslims.

In this investigation, I aim to delve into the intricate relationship

between education, modernity, and social reforms within Sir Syed’s intellectual

framework as depicted in Tehzib-ul Akhlaq.

Transformation

Of An Idea Into Tehzib-Ul-Akhlaq

While

residing in Banaras, Syed Ahmad Khan received news that his son, Syed Mahmud,

had been granted a scholarship by the British government of India to pursue

higher studies in England. Filled with excitement and anticipation, Sir Syed

and his son embarked on their journey to London on April 1st, 1869. It was

during their time in the vibrant city of London that Sir Syed came across two

influential social journals, namely Spectator and Tatler, which focused on

societal reform. Inspired by the ideas presented in these journals, Sir Syed

conceived the notion of creating a publication aimed at reforming Indian

Muslims.

Expressing

his vision to his dear friend Nawab Mohsin-ul Mulk through a letter, Sir Syed

shared his decision to launch a journal solely dedicated to the betterment of

Muslims. He revealed the intended names for this publication,

“Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq” in Persian and “Mohammedan Social Reformer” in English. Upon returning to Banaras, Sir Syed put his

plans into action and introduced Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, a journal intended to bring

about social reformation among the Muslims of India. The inaugural issue of

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq was published on December 24th, 1870. Although the journal faced resistance from

some segments of the Indian Muslim community, it also garnered support from

individuals such as Nawab Mohsin-ul Mulk, Maulvi Muhammad Chiragh Ali Khan,

Maulvi Mushtaq Hussain, Maulana Altaf Hussain Haali, Shamsul Ulema Maulvi

Zakaullah, Shamsul Ulema Allama Shibli Nomani, Maulvi Mehdi Hasan, Syed

Mahmood, and Sir Syed himself, who contributed numerous articles on social and

religious reforms. Over the years, Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq experienced temporary discontinuations,

but it ultimately merged with Aligarh Gazette in 1881, marking the culmination

of its impactful journey from its inception in 1870 until 1981.

Sir

Syed’s Deep & Personal Connection With Education

Those

familiar with the history of Muslim education in India are well aware that

Indian Muslims were deeply dissatisfied with the educational system imposed by

the British alliance. Since the early days of British rule, the foundations of

the Indian educational system, particularly for Muslims, started to crumble.

The British introduced a new form of education aimed at producing educated

individuals to serve their interests. This approach, influenced by Macaulay's

policy, advocated for Western education as the sole means of India’s progress. Muslims strongly opposed English education

from the very beginning, primarily due to concerns that it eroded their faith

and allowed for the spread of Christianity. Some were so vehemently against

this form of education that they preferred to keep their children uneducated

rather than sending them to English schools. They believed that the traditional

Arabic madrasas provided sufficient education for their children. However,

remaining confined within these madrasas, without the opportunity to benefit

from the intellectual advancements of other nations, was seen as

self-destructive. While the educated Muslim landlord class, in general,

disapproved of the European system of education, there were some individuals

within this class who sent their young men to English colleges like Delhi

College and Fort William College in Calcutta.

Therefore, a small number of Muslim youth received a Western education

during the first half of the nineteenth century, but the community as a whole

remained aloof. It was in response to these challenges that Muslims began to

focus on establishing their own educational institutions. By the turn of the 20th century, Indian

Muslims faced a division regarding the balance between Islamic and Western education.

Sir Syed

held a deep and personal connection with education. He viewed education as a

powerful tool to open the doors to the western world and saw it as the key for

Muslims to progress and overcome their challenges. The Tehzibul journal

dedicated a significant amount of attention to education, publishing around 30

articles that covered various aspects of this crucial topic. Notably, individuals such as Mirza Abid Ali,

Munshi Mohamed Yar Khan, Nafees Bano, Nawab Vaqarul Mulk, and Mohammed Enyatur

Rehman, alongside a few others, also directed their focus towards education.

The journal further included articles from reputable publications like the

Pioneer, the Friend of India, Kohinoor, Oudh Akhbar, Njamul Akhbar, and Punjabi

Akhbar, among others, emphasizing the importance of education through this

diverse range of sources.

In one of

his articles titled "Religion and General Education," Sir Syed

expressed his belief that the expansion of education could only be achieved

through the integration of religious education. He further discussed the Dars-e

Nizami (Nizamia Tariqa-e-Taleem ) and highlighted how the existing curriculum,

designed to provide comprehensive knowledge to students, was no longer suitable

for the present times. Within the pages of Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Sir Syed covered a

range of topics, including education in Persia, the shortcomings of current

educational practices, the relationship between education and social status,

and the importance of Muslims embracing the learning of the English language.

These articles served as a testament to Sir Syed's dedication to exploring

various aspects of education and its significance.

In his

thought-provoking article "Talab-e llm" (Quest for knowledge),

featured in the esteemed publication Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Mirza Abid Ali

eloquently expresses how the thirst for knowledge acts as a catalyst, fostering

the holistic growth of an individual. Education, in its essence, ignites a

profound desire for the liberation of one's thoughts and the attainment of

self-discovery.

In his

enlightening article titled "A perceptive analysis of progressive

education in India," published in Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Munshi Mohammed Yar

Kha shares his insightful perspective.

He astutely points out that the existing education system in India falls short

in cultivating intellectual sharpness, as it fails to instill in students the

necessary perseverance to overcome obstacles that come their way.

Nafees Bano

penned an insightful piece on education, meticulously organizing it into four

expansive sections: Exploring the traditional framework of education, examining

the significance of modern education, advocating for a greater focus on

nurturing alongside education, and presenting practical suggestions for the

establishment of educational institutions and their inherent value.

In his

insightful article titled "The Significance of Education and the

Transformative Journey of Students," Nawab Vaqarul Mulk delved into the

conventional educational system and highlighted its impact on students, urging

them to lead lives of seclusion within the confines of religious seminaries.

Consequently, the nurturing of crucial attributes such as self-esteem and

bravery remained stifled. Instead, traits like timidity, egotism, selfishness,

and an unrepentant attitude began to thrive.

In his

thought-provoking article titled "Knowledge and its Attainment" (llm

aur Uski Tahseel), Mohammed Enyatur Rehman delved into the intricate journey of

acquiring knowledge, highlighting the numerous challenges and obstacles one

encounters along the way.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, known for its remarkable collection of content, often sought

inspiration from esteemed newspapers like the Pioneer, The Friend of India, The

Times of India, Shamsul Akhbar, Punjabi Akhbar, and Najamul Akhbar. Allow me to

share a few captivating excerpts from an article featured in The Friend of

India:

“Before the

advent of the British is India the Mahomedans Government did not recognize

public education as a duty of the state at all. Such a thing as a department of

public instruction was unknown, and the imperial treasury was never opened to

rise to moral and social conditions of the large population, which supplied the

emperors of Hindoostan with means of grandeur and magnificence. No doubt the

enlightened generosity of individuals had here and there founded the colleges

of a semi-religious description, and private endowments supported a large

number of teachers and pupils connected with these institutions. No can deny

that the education imparted by their colleges succeeded in producing great theologians

and scholars, lawyers and historians, writers and poets, who commanded the

greatest respect of their countrymen and have left behind them merits of their

genius upon the language and literature of this country. But a system of

education such as it was confined to the Musal men only; and Hindoos seldom or

never availed themselves of the modem learning which their Mahomedans

conquerors had brought from these regions of Asia, which had benefited by the

influence of the Arabian school of philosophy.

We are,

therefore, justified in saying that the Mahomedans rulers of India did not

consider the education of the people as a business of the state in the same

sense in which it is regarded now. The British Government, however, in common

with other civilized nations, has fully recognized public instruction to be a duty of the state,

and: indeed maintains a separate department for carrying out its educational

policy. Annual reports by Directors of Public instruction are invariably

entitled. "Reports on the Progress of India" and in this respect the

Department of Public Instruction has a satisfaction, which perhaps no other

department can claim.

We,

however, do not wish to dispute about words and phrases: we intend to deal with

facts and wish to discuss the actual results which have either accrued or are

likely to accrue, from the system of public education adopted by the Government

in India.

When the

English succeeded the Musalmans in the supremacy of India, the Hindoos found no

difficulty in reconciling themselves to the new state of things. The change of

rulers made no great difference to them and they look to English as their

successors had taken to Persian. But the Musalman, who notwithstanding the

downfall of his race, had still sparks of ancestral pride in his bosom, looked

with contempt upon the literature of a foreign race, apposed all reform, and

ignorance contributed to encouraging him in his opposition. He obstinately

declined either to learn the English Language or modem science, still looked up

with veneration to those mysterious volumes which contained the teaming of his

forefathers, and reconciled himself to his position by a firm belief in

predestination. The result was a great political evil.

A large

number of Hindoos had acquired knowledge of the English language and thus kept

pace with the times, and some of them rose to the highest offices under the

English Government The Mahomedan, on the contrary, remained stagnant,

remembered with pain and sorrow the past power and the prestige of their race,

and still continued to worship the learning contained in Arabic and Persian

literature. The surrounding circumstances grew too powerful for them, and they

gradually sank into ignorance, poverty and degradation...

The

education, which the students receive in Government College, does not develop

the intellectual or moral side of human nature and years of training do not

improve his mode of thought or social habits... The Government educational

Institutions can without exaggeration be described to be a mixture of the lower

class of English private and public schools having the disadvantages of both

and the advantages of neither, and we are not surprised to find the natives of

a good position are not anxious to patronize them.

The

principle, upon which the department of Instructions is now based, does not

meet with our approval. It is carried in a manner unknown to any other country.

Appointments of professors are made without any reference to their

qualifications, and the numbers of years they have served in the department

guide their promotion”.

Religion

Is A Word Of God & Nature Is The Work Of God

The

foundation of Tehzib-ul Akhlaq's articles revolved around the profound notion

that "Religion is a word of God and nature is the work of God." Their

philosophy rejected the reliance on outdated concepts, rigid beliefs, and

superstitions in religious matters, advocating instead for a focus on

rationalism and its intrinsic connection to the natural world. The publication

dedicated a substantial portion of its content to religious topics, with

prominent contributors such as Sir Syed, Maulvi Chirag Ali, Mohsinul Mulk,

Maulvi Enayat Rasool, Vaqarul Mulk, Altaf Hussain Hali, and a few others.

Sir Syed, a

prolific writer, penned numerous articles delving into religious matters. In

one of his thought-provoking pieces titled "The Question of Belief in

Islam," he explored the fundamental principles upon which the religion

should be built. According to him, Islam ought to derive its essence from the

natural order and harmonize with the inherent nature of humanity. In another

enlightening article called "Religious Thoughts in Ancient and Modern

Age," he examined the disparities between the doctrines of the past and

present. Moreover, Sir Syed's remarkable

work, "Tafsirul Samawat," critically scrutinized the claims

made by certain Islamic scholars who argued that the stars were etched onto the

sky. He believed that such a perspective contradicted the Quran's depiction of

the celestial realm. In yet another captivating article titled "The World

of Ideas," Sir Syed highlighted:

"Religious

debate has a strange tendency if a trivial question is discussed, it would

entail a discussion on a big question and the principle of religion. Hence

sometimes one has to turn attention to Islamic jurisprudence and sometimes one

is forced to ponder over the principles for writing a commentary on the Quran.

India not only requires Steele and Addison but also stands in need of holy

Luther”.

Mohsinul

Mulk, an insightful writer, crafted a collection of nine articles encompassing

various facets of religion. In his compelling piece titled "Islam,"

he boldly asserted that Islam vehemently opposed the uncritical adherence to

venerable traditions, narrow-mindedness, irrational behaviour, obscurantism,

and blind conformity to customs. He further emphasized that embracing modern

knowledge did not diminish the validity of one's Islamic faith. In his

thought-provoking article "Tafsir Bil Rai," Mohsinul Mulk explicitly

highlighted the compatibility between the Quran and the laws of nature. He

stressed the importance of maintaining a harmonious balance between the

interpretation of the Quran and the principles of natural laws and

causality.

In his

insightful article titled "Haiyat-e-Jadida aur Mojaz-e-Quran," Vaqarul

Mulk passionately argued that there could never be any contradiction between

the Word of God and the Creation of God. He firmly believed that reason served

as the wellspring for comprehending the divine teachings. According to him, by

utilizing our reasoning abilities, we could gain profound insights into the

divine messages conveyed through the Quran.

In a

thought-provoking article titled "Qissa-e-Adam Wajood Kharji

Shaitan," Maulvi Obaidullah Obaidi offered his unique perspective on the

story of Adam (pbuh). He intriguingly proposed that Adam should be viewed as an

archetype, and his narrative ought to be approached as a fable, carrying

symbolic significance. Furthermore, Maulvi Obaidi controversially challenged

the existence of angels and jinn, presenting his dissenting viewpoint on these

supernatural entities.

Fostering

A Sense Of Social Responsibility

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq not only dedicated its pages to social reform, but it also

played a significant role in fostering a sense of social responsibility. The

publication consistently featured articles that aimed to ignite a collective

desire for positive change within society. Sir Syed's influential article

titled "Uncivilized country and uncivilized Government" passionately

discussed the principles of equality, social justice, dignity, and honesty,

shedding light on their utmost importance.

In his thought-provoking piece, "Rasm-o Rivaj" (Custom

and Habits), he eloquently argued that while every country embraces its own set

of customs, it is the adherence to these traditions that grants them a distinct

cultural identity. Nevertheless, he emphasized that no country should consider

itself culturally superior to others.

Moreover,

Sir Syed's profound insights extended to various other subjects, as seen in his

articles on "External virtue," "Life style," "Breeding

of children," "Dinning code," "Man and animal,"

"Relationship between Religion and the world," "Complying with

the civilized nation," "Progress of Man," "Eid," and

numerous others. Each of these articles, published in the journal, aimed to

drive societal progress and reform. They

tackled issues ranging from personal conduct to the intricate dynamics between

religion and the world at large. By shedding light on these topics, the

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq and Sir Syed Ahmed Khan made a significant contribution to the

ongoing pursuit of a more just, inclusive, and enlightened society.

Conclusion

In

conclusion, Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq encompassed a broad vision and emphasized the

importance of modern education to uplift the social and economic conditions of

Muslims in India. It never dismissed the significance of religious and oriental

studies, as Sir Syed and his contemporaries extensively discussed these topics

in the journal. Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq served as a medium to advance Sir Syed's

campaign for promoting modern education, religious interpretation, and social

reforms among Indian Muslims. The journal aimed to create awareness about good

social conduct, etiquette, morals, manners, and the requirements of civilized

behaviour. Its articles primarily focused on disseminating education, awakening

the Muslim community, and advocating social and religious reforms, intending to

stimulate curiosity and rational thinking among its readers. Given the present

times, it is worth pondering whether we can draw inspiration from

Tehzib-ul-Akhlaq to meaningfully contribute to the broader issue of empowering

Muslims. Shibli Nomani, while acknowledging his disagreements with some of Sir

Syed's ideas on religion and progress, greatly admired Sir Syed's style of

expression.

-------

'Tehzib ul Akhlaq’ which greatly succeeded in

infusing a new desire amongst Muslims for acquiring modern knowledge. It also

gave a new direction to Muslim social and political thought. Along with his

search for a solution to the community’s backwardness, he continued writing for

various causes of Islam without prejudices against any religion. See An special

issue on Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: A Global Phenomenon, Muslim Mirror, February

2014.

Sir Syed knew that in the past, Muslims

excelled in the field of technology, business, medicine and other professions

of life. But the same community had distanced away from these fields and

started believing that acquiring the knowledge of these fields is a blasphemy.

Masood Ross Sir Khutoot-e-Sir Syed, Nizami

Press, Badaun, 1924 Page no 54. Before launching the Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Sir Syed

had started two bilingual periodicals - the Loyal Mahomedans of India and the

Aligarh Institute Gazette and both carried different names in Urdu and English.

In line with it, the masthead of the new journal carried two names –Tehzib-ul

Akhlaq (Urdu) and the Mahomedan Social Reformer (English). Sir Syed was the

first Urdu journalist who started publishing the motto of the journal at the

front page. Sir Syed was not only the editor but was also the main contributor

to the journal. He wrote the entire contents of many issues.

Sir Syed visited England in 1869 and that

time the Tatler and the Spectator were no longer in existence; in fact, they

were closed down more than 150 years ago. How did Sir Syed come to know about

them? He himself answered this question in his journals in one of his articles.

For detail see The Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Muhairamul Harram 1289 Hijra (March

23, 1871). Also see Siddiqui, M Ateeq Sir Syed Ek Siyasi Muttala, Maktaba

Jamia, Delhi, 1977, Page no 125. Also see Altaf Husain Hali, Hayat-e Javed, p.

12.

The Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, since its inception was

published under the stewardship of Sir Syed. When it was launched, Sir Syed was

posted at Benaras and he used to edit the journal from there.

Revival of Tehzib-ul Akhlaq: After a century

later, in 1981, a staunch supporter of Aligarh Movement and an AMU alumnus,

Syed Hamid, the then Vice-Chancellor of Aligarh Muslim University felt the need

of Tehzib-ul Akhlaq. He discussed the idea with few learned members of

concerned of community and re-started Tehzib-ul Akhlaq as a Bi-monthly private

journal. A committee was formed, Chief Editor: Mr Syed Hamid (Vice-Chancellor,

Aligarh Muslim University), Editor: Mr Qazi Moizuddin (Aligarh), Treasurer: Dr

Manzar Abbas Naqvi (Dept. of Urdu, Aligarh Muslim University). Also see

http://aligarhmovement.com/Institutions/Tahzibul_akhlaq

Jamia, Jashn-I Zarrin Number, ed. Ziya ul

Hasan Faruqi, New Delhi, November 1970, Abd ul Latif Azmi, “Jamia ke Pachas

Sal,” pp. 9-10.

Ibid., p. 10 & Tarachand, op. cit., vol.

II, p. 351.

Tarachand, op.cit., vol. II, p. 351 and

Daktar Zakir Husayn, Zakir Husain Memorial Committee, Hyderabad, 1972, pp.

28-9. Asbab-e-Baghaawat-e-Hind (Causes of the Rebellion of 1857), a treatise

published in 1859 that attempted at drawing the colonial state’s attention

towards reasons such as Christian conversions, lack of opportunities and unfair

handling of the natives (Muslims in particular) by the British officials. The

work, without questioning the essential foundations of colonial supervision,

aimed at correcting the perception of the British vis-à-vis Indian Muslims.

Also see Ali, Parveen Shaukat (2004), Islam

and the Challenges of Modernity: An Agenda for the 21stCentury, Islamabad:

National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence,

Quaid-e-Azam University.

Out of which Sir Syed contributed 14 for

instance articles on the importance of education; the concept of education,

progress of education, benefits of education and the pivotal role of education

is shaping one's personality. Also see Robinson, Francis (2000), Islam and

Muslim History in South Asia, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Tehzib-ul

Akhlaq.

The

most popular syllabus of religious schools.

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq.

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Moharram 1288.

The

first editor of the Aligarh Institute Gazette.

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq.

Nafees

Bano, Tehzib-ul Akhlaq: A critical study, Education Book House, Aligarh, 1993,

Page 278.

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Jamiuds Sani, 1288 Hijra.

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, an article from the newspaper ‘The Friend of India’.

For

detail see The Tehzib-ul Akhlaq from the beginning of Shawwal to Ramdhan 1296

Hijra translated into English by M. Hameedullah, included in selected Essays of

Sir Seyed Academy, AMU, 2004, Page 39 to 42.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Shawwal 1312 Hijra.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Zeedaqad IS, 1287 Hijra.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Zeeqad, 1287 Hijra.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Zeeqad 1288 Hiira.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Rahdhan, 1292 Hijra.

Siddiqi, Hamid Raza (2014), “Sir Syed Ahmad Khan ke Islaahi Kaarnaame”,

Tahzeebul Akhlaq33 (10): 194-199.

The

Tehzib-ul Akhlaq, Yakum Rabius Sani. Also see Metcalf, Barbara (1982), Islamic

Revival in British India: Deoband, 1860-1900, Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

------

Javed Akhatar is Assistant Professor (Contractual),

Department of Islamic Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia

New Age Islam, Islam Online, Islamic Website, African

Muslim News, Arab World News, South Asia

News, Indian Muslim News, World Muslim

News, Women in Islam, Islamic Feminism, Arab Women, Women In Arab, Islamophobia in America, Muslim Women in West, Islam Women and Feminism