Progressive Muslims Were Leftists Steeped In Islamic Culture By Way Of Mannerisms and Attire

By

Ghazala Wahab

MAR 06,

2021

In the

years after Independence, especially after the passing of the leaders of the

freedom movement, the contours of Muslim politics changed from secular and

nationalistic to largely parochial and conservative. Diverse types of

leadership then emerged.

One (and

this was the minority) was of ‘progressive’ Muslims, fired with Communist

ideology. According to Congress politician, lawyer, and author Salman Khurshid,

‘The “progressive” Muslims were Communists or Leftists. Though steeped in

Islamic culture by way of mannerisms and attire, they were not always

practising Muslims.’ What’s more, they did not see themselves as

representatives of Muslim interests alone. Their politics, though

nationalistic, was aligned with the international Communist movement. A large

number of ‘progressive’ Muslims, especially the litterateurs, identified with

Communist ideology because of its emphasis on social justice. This was because

they found echoes of the Islamic principles of equality and fraternity in the

ideals of Communism. Hence, even though their respective parties may have

viewed them as Muslims, neither they nor their constituents regarded them as

Muslim politicians because they did not conform to what was expected of a

Muslim—as a result, few of them won elections.

Another

type comprised the conformists. For this lot, how their constituents viewed

them mattered greatly because their relevance in politics depended on their

ability to win elections. In their perception, religion was not just a matter

of personal faith, but a qualification for practising politics. Hence, they had

to not only look Muslim but also be more Muslim than others. ‘We have to

conform to the expectations of our constituents,’ admits Khurshid. ‘It helps us

connect with them. Hence, issues like Namaz and Roza become

important because these are the questions politicians like us are asked by our

constituents.’ The dichotomy here is that many of these politicians are

progressive in their outlook but are often forced to take regressive positions.

Instead of inspiring their constituents to become progressive or liberal, they

fuel religious conservatism.

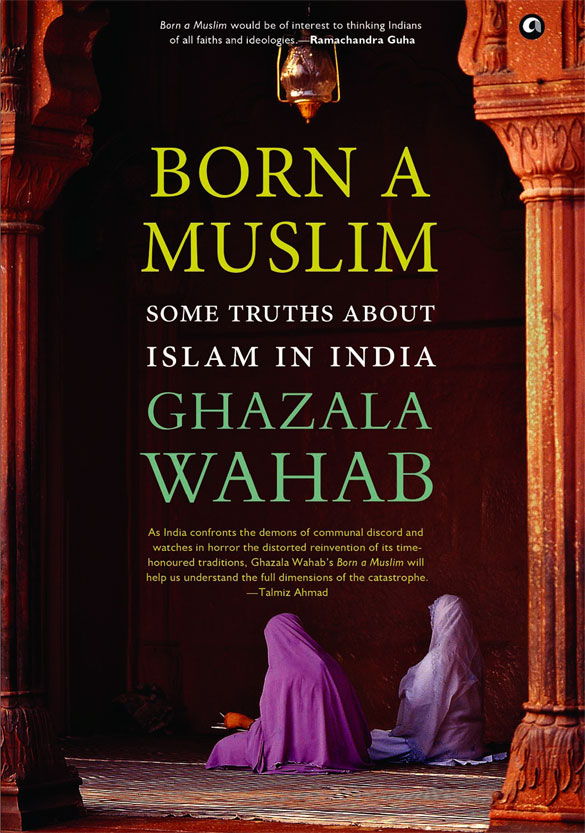

Women

protest at Shaheen Bagh. Photo: PTI

-----

Historically,

Muslims, by and large, from the days of the caliphate onwards have regarded

spiritual and temporal powers as unified. Even in later centuries, when

hereditary dynasties took over the function of governance, the kings maintained

the façade of being guided by divine law. The ulema were part of the court.

When the Mughal Empire fell, the ulema effortlessly moved into the role of

community leaders, as a kind of a bridge between the state and the people.

Subsequently,

when non-religious Muslim politicians emerged in the beginning of the twentieth

century, their focus was the political representation of their class of

Muslims, which was the Shurafa, rather than the uplift of the

downtrodden. To discredit them as representatives of the larger community, the

‘nationalist Muslims’, essentially members of the Indian National Congress,

turned to the ulema, mainly from the Darul Uloom Deoband and its Delhi-based

associated group, Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, to steer the Muslim masses towards the

Congress and its politics. Explaining this paradox of supposedly liberal

politicians seeking Muslim support through its least liberal entity, the ulema,

Khurshid says that once the educated class—the AMU crowd and the landed gentry—

drifted towards the Muslim League, thereby according it legitimacy, the

Congress party had to find a new class of grassroots leaders whom the masses

could identify with. In their perception, the ulema had that sort of persuasive

power to steer the masses towards the Congress.

‘There was

no choice but to pick potential leaders from the madrassas,’ says Khurshid. ‘I

had once asked the senior Congress leader Narayan Dutt Tiwari why most of the

Congress leaders were Brahmin. He said that was because Brahmins could mobilize

people at the grassroots level. In a similar manner, the catchment area for

Muslim leadership became the madrassas.’

There was

another reason why the Congress party gravitated towards the ulema of Darul

Uloom Deoband. Between 1913 and 1920, the ulema from Deoband ran an underground

campaign which came to be known as Reshmi Rumaal Tehreek (Silk Scarf

Movement) that sought the support of Afghan and Turkish rulers to overthrow the

British. On the pretext of travelling to Mecca, the Deoband ulema travelled to

Afghanistan and Turkey to garner support. Messages were relayed through silk

handkerchiefs, hence the name. They managed to get some support from both the

Afghans and the Turks. What’s more, they established communication and

collaboration with the Ghadar Party, an underground movement formed by Punjabi

peasants working in the west coast of the United States. Most of them were

former soldiers of the British Indian Army who had migrated to the US after

their military service and worked as labourers in parts of California. The

British eventually caught on after some silk letters were confiscated from

Punjab. The main conspirators, the leading ulema from Deoband, were arrested

and deported to Malta.

Even though

the ulema were trying to wage a jihad against the British, it is not clear what

kind of British-free India they sought—an Islamic India or a multi-religious

and multicultural country. Nevertheless, Reshmi Rumaal Tehreek

established the reputation of the Deoband ulema as nationalists, as opposed to

the Barelvis who had thrown their weight behind the Muslim League. The general

secretary of Jamiat Ulama-i-Hind, Maulana Mahmood Madani, says with a measure

of pride, ‘The ulema of Deoband participated in the freedom struggle alongside

Gandhiji.’ In January 2013, President Pranab Mukherjee released a stamp

commemorating the efforts of the ulema involved in the movement.

The ulema

benefitted greatly from this aspect of their historical evolution. So even when

university-educated, professionally-qualified Muslims sought a political

career, they felt compelled to co-opt the ulema. This gave rise to the

perception that to represent Muslims the leader must be, or at least appear to

be, religiously conservative. A Muslim mainstream politician, therefore,

started carrying a twin burden. He (it has rarely been she) would need to

appear to be devout for the benefit of his Muslim constituents and flaunt his

liberal credentials to his party and possible non-Muslim voters, lest he be

considered illiberal or communal. A consequence of this balancing act has been

that Muslim politicians are reluctant to raise issues that genuinely affect the

community and call for changes in government policy or even the accountability

of law-enforcement agencies. For instance, prejudice in government employment,

harassment in the name of security, the blatantly partisan behaviour of state

police forces, and, most importantly, the bogey of terrorism—all of which are

frequently invoked to harass Muslim youth are issues that mainstream Muslim

politicians rarely take up. Instead, they dabble in the same issues that the

ulema do, such as the protection of Islam, Urdu language, Muslim Personal Law

and so on.

***

Interestingly,

a small section of these Muslim conformists has also aligned itself with the

Hindu right wing. The BJP has always had a few token Muslim politicians in its

ranks—these politicians are projected to seem bigger than the influence they

really wield, both within the party and amongst the voters. However, these

representatives of inclusiveness are so powerless that they are unable to

register even a token protest when their fellow right-wing hardliners victimize

Muslims.

Despite the

necessity for minority representation in a democracy, the truth is that Muslim

politicians essentially cannot do much to better the lot of the Muslim masses.

Their position and power within mainstream political parties is limited to

getting a few votes. Their own self-interest, insecurity, and likely inability to

connect with the Muslim masses (because of their repeated failure to deliver)

have rendered most of them irrelevant within their own parties.

This leads

to a few questions. Who do the Muslim politicians represent? What is it that

they do which non-Muslim politicians cannot do? Are there issues that pertain

to Muslims alone, which only a Muslim politician can address, or would a

non-Muslim be more effective in doing so? Why can’t a Muslim politician be

regarded as a regular mainstream politician, shorn of his Islamic identity?

***

Another

kind of Muslim political leader wields influence from behind the scenes. These

strongmen usually belong to organizations that have consolidated influence at

the grassroots level. Leading the pack is the All-India Muslim Personal Law

Board. It came into being, unsurprisingly, to protect Islam which was facing

multifarious threats, both from dissenting Muslims like reformer Hamid Dalwai

as well as non-Muslims.

In March

1970, Dalwai established the Muslim Satyashodhak Mandal (Muslim Truth-Seeking

Society) in Pune to work towards reforming Muslim Personal Law. Two years

later, in December 1972, ulema of various hues got together to establish the

AIMPLB to (among other issues):

Take

effective steps to protect the Muslim Personal Law in India and for the

retention, and implementation of the Shariat Act;

Strive for

the annulment of all such laws, passed by or on the anvil in any State

Legislature or Parliament, and such judgments by courts of Law which may

directly or indirectly amount to interference in or run parallel to the Muslim

Personal Law or, in the alternative, to see that the Muslims are exempted from

the ambit of such legislations;

Set up an

‘Action Committee’ as and when needed, for safeguarding the Muslim Personal Law

through which [an] organized countrywide campaign is taken up in order to

implement decisions of the Board;

Constantly

keep watch, through a committee of Ulama and legists, over the state or Central

legislations and Bills; or Rules framed and circulars issued by the government

and semi-government bodies, to see if these, in any manner, affect the Muslim

Personal Law.

Although in

conversation with me, the AIMPLB’s spokesperson, Kamal Farooqui, listed social

reforms as one of the objectives of his organization, the reforms that he spoke

of were similar to the ones pursued by religious sects like Deoband, i.e.

removing extraneous influences from Islam and ridding the Muslims of social

evils like dowry, ostentatious weddings, and un-Islamic rituals. The AIMPLB

came into its own when it spearheaded the campaign against the Supreme Court

verdict in 1985 on Shah Bano’s case. This forced Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s

government to overrule the court, and instead pass the Muslim Women (Protection

of Rights on Divorce) Act in 1986.

------

The

above is an extract from the chapter ‘Minority Politics’ in Ghazala Wahab’s new

book Born a Muslim: Some Truths About Islam in India (Aleph Book Company).

Ghazala

Wahab is executive editor of FORCE magazine.

Original

Headline: Minority Politics: Notes on

How Muslims Have Been Political in India

Source: The Wire

URL: https://newageislam.com/books-documents/progressive-muslims-were-leftists-steeped/d/124505