Women Rise Up in Saudi Arabia: The Rebellion behind the Veil

By Karen House

Jul 30, 2012

Two Saudi women are competing for the first time in London. Thousands are daring to challenge the status quo at home.

A Remarkable thing happened this past May in Riyadh. Officers belonging to Saudi Arabia’s ever-zealous religious police, the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, ordered an Abaya-clad young woman out of a shopping mall for wearing nail polish. That in itself wasn’t so unusual. The surprise was what came next: the young woman stood her ground. She told the men they had no right to harass her, filmed the confrontation on her Cellphone, and posted it on YouTube, where it quickly went viral.

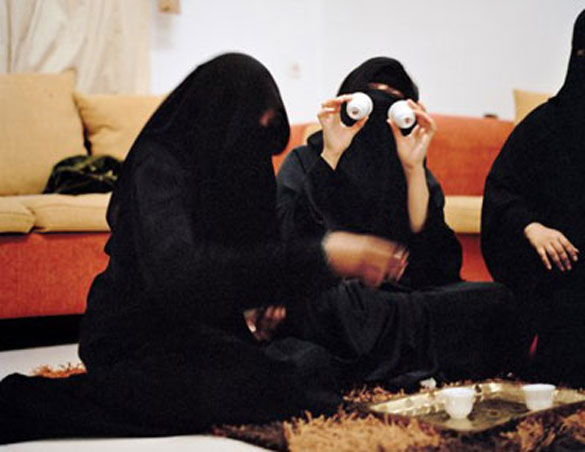

Olivia Arthur / Magnum Photos

----------

Public protests like hers may still be rare in Saudi Arabia, but they are getting less so. Manal al Sharif, a divorced mother, was employed by the oil giant Saudi Aramco. Last year she was arrested for daring to drive a car, and her case drew worldwide attention. When the organizers of a human-rights forum invited her to Oslo to receive the Václav Havel Prize for Creative Dissent, her bosses warned that she would lose her job if she insisted on attending. She quit and went to Oslo.

Don’t be misled by news that Saudi women are competing in the Olympics this summer. The truth is that the participation of the two women athletes is little more than a sideshow, a distraction from the challenges faced by millions of other women back home in the kingdom, where the government continues to enforce the Wahhabi Islamic doctrine that just as man must obey Allah, woman must obey man. The attempted diversion is very cynical—and very Saudi. As this story went to press, in fact, the Saudi women’s presence in London hadn’t even been mentioned in the state-controlled media. Too many conservative Saudis would have objected.

Ever since the founding of modern Saudi Arabia in 1932, the ruling al-Saud family has kept itself in power through a combination of divide-and-conquer tactics, dollars, and duplicity. These days, however, the old tricks are losing their effectiveness. They just don’t work so well anymore, now that education and the Internet have raised awareness among the kingdom’s subjects and made public affairs at least slightly less opaque. Having travelled extensively throughout the country over the past five years, talking with Saudi men and women of every region, sect, and socioeconomic background, I have no doubt that the pressure is growing—and that Saudi women are the strongest advocates of change. At the cutting edge are a relatively small number of women brave enough to defy authority openly. But behind them is a generation of women who are deeply, if quietly, dissatisfied with their second-class status, and doing what they can to rectify the situation.

So far, these agents of change remain a minority among the kingdom’s women. The typical Saudi woman is more like the devout Muslim mother of seven who invited me to share life in her Riyadh home. Lulu, as she’s known, lives on the second floor of a house surrounded by high walls. The apartment downstairs is the home of her husband’s first wife, who has eight children. The two wives don’t mix. Instead, their husband shuttles up and down the stairs, dividing his time equally between the two women. “It is natural that sometimes there is jealousy,” Lulu says, “but I just say ‘Allhumdulillah’”—Arabic for praise be to God.

Lulu rarely leaves her house. That’s her choice, she says: she has no interest in driving or just about anything else outside her home. Instead, she devotes herself to serving her husband and to ensuring that her children are sticking to a strictly religious path. She keeps the television tuned to the kingdom’s religious channel, where women never appear, and she maintains careful control over the family’s one computer. Its main use is as a tool for her children’s studies, but she made an exception to that rule when she attempted to proselytize me with an hour-long YouTube video of a Texas man who says he used to be a fundamentalist Christian preacher, explaining his conversion to Islam.

Although Lulu studied at King Saud University in her younger years, she now seems interested in no career other than rearing her children to lead a life precisely like her own. When she must go out in public, she shrouds herself in a flowing black Abaya, headscarf, and a face-concealing Niqab. She gently tells me that my own Abaya is immodest: it fits across my shoulders and has a narrow band of orange and blue braid on the sleeves. “This is wrong,” she says, “This decoration attracts men to look at you.”

As storms of social upheaval sweep the Middle East, women like Lulu take comfort in their lives of cloistered conservatism. Still, even Lulu has to admit that many Saudi women no longer share her willingly submissive attitude. I have listened as women across society expressed their longings for change. They came from strikingly diverse backgrounds: privileged working women, impoverished widows in the slums, aspiring female law students in a private university, battered wives seeking protection from brutal husbands, even one of King Abdullah’s own daughters.

Olivia Arthur / Magnum Photos

--------

I think back to an evening when I was invited to tea with a group of Saudi professional women. All spoke excellent English. All graduated from King Saud University in Riyadh, and all were the daughters of educated mothers who encouraged them to pursue careers outside the home. The guests that evening included an event planner, an elementary-school principal, the owner of a small business, and a trainer in cosmetology. All had traveled to Europe and dressed in expensive Western clothes. By Saudi standards, they all had everything a woman could ask for: drivers, nannies, even husbands who supported—or at least accepted—their careers. Nevertheless, they made no secret of their frustration with the restrictions the country places on women’s freedom, and with the ubiquitous religious police who enforce those limits. “We want choices,” said the cosmetology trainer. “We want to work or not, drive or not, shake hands or not.”

She’s lucky compared with Umm Muhammad. Uneducated and in her 40s (her father didn’t let her go to school as a child), the widowed mother of seven supported her children by peddling scarves and Abayas outside a Jeddah shopping mall, in the scorching heat, until the mall’s owners evicted her. She didn’t fold her little awning and give up. Determined to support her family without relying on government handouts, she sought help from the Khadijah Women’s Centre at the Jeddah Chamber of Commerce, and she secured a loan to open a new stall, near another mall in the city.

But Umm Muhammad has far bigger dreams. Her late husband, an auto mechanic, taught her the trade before his death. Now she’s pressing for the licenses necessary to open a car-repair shop of her own. So far the Jeddah municipality has refused—after all, she’s a woman. But with courage and persistence like hers, who knows? And the fact that she’s trying says a lot about the determination of Saudi women.

Her willingness to challenge the status quo is shared by Maha al-Fozan, one of the first female law students ever at Prince Sultan University. Fozan is confident that women will soon be allowed to represent clients before Saudi Arabia’s Sharia judges—so confident that she has been willing to invest three years of her life in law school preparing to plead cases in court. Female lawyers are already at work behind the scenes preparing cases for battered women and other female clients, even if the victims still have to rely on male lawyers to represent them in court.

Such cases are multiplying, thanks to women doctors who have become more willing to report cases of abuse. In the past, the problem was dealt with only as a private matter because women and children are legally the property of men, says Dr. Maha al-Muneef, the U.S.-trained executive director of Saudi Arabia’s National Family Safety Program. But now, she says, abuse is coming to be understood “as a crime, not just a family affair.”

It can take a tough woman to negotiate the complexities of Saudi family law. Fatima Mansour, a poor, uneducated woman, was happily married to a man from a lower-ranking tribe. Their contentment ended when her half-brothers took her to court, seeking to force her to divorce the man. The half-brothers claimed that her husband had deceived their father into giving his consent to the marriage—and the judge ordered that the marriage be dissolved. Fatima refused to comply. She knew she couldn’t go home to her husband; if she did, it would constitute adultery under Saudi law, and she feared that her half brothers would kill her for what they regarded as bringing shame on the family. Instead, she demanded to be incarcerated with her year-old daughter while she appealed the judge’s ruling.

The couple’s plight finally caught the attention of Princess Adelah—and eventually that of her father, King Abdullah. The princess has played an active role in helping advance the status of women in Saudi society ever since Abdullah ascended the throne in 2005. She holds no official position in the government; only one Saudi woman has ever risen even to the level of deputy minister (her portfolio is women’s education), and she is so cautious that she speaks to her male colleagues only by video conference, and with her face veiled. The princess, asked if she resents doing volunteer work while her brothers run the National Guard, serve as deputy foreign minister, and hold office as provincial governor, says an official position would be a burden. “I can work for the causes I want,” she says. “If I don’t use my name and status to make a difference, I don’t deserve to be who I am.” Nearly five years after the half-brothers took Fatima to court, the king asked a supreme judicial council to review the case, and soon the couple was reunited.

The hope is that as Saudi women push for their rights, they will someday take part in the Games for real. This year’s two-woman team needed a special invitation from the International Olympic Committee because Saudi Arabia failed to hold any qualifying trials for women. In fact, physical education is banned in most girls’ schools. Some international schools do have teams for girls, but religious authorities often shut down their competitions even when the only spectators are females. Women’s sports are generally regarded as a waste of time at best—and at worst, a slippery slope to decadence. For one thing, athletic clothing is considered immodest. But worse yet, sports somehow might lead to the mixing of unrelated men and women—a terrible sin in the eyes of the kingdom’s conservatives.

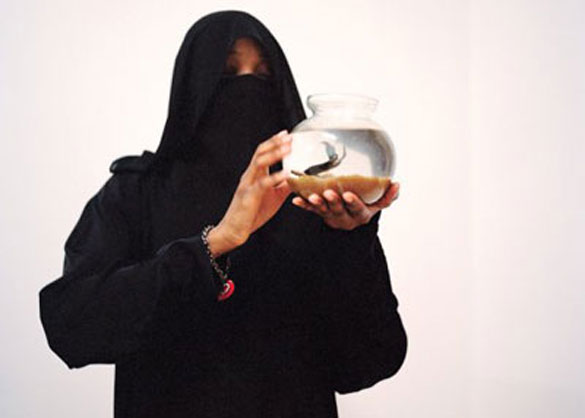

Olivia Arthur / Magnum Photos

---------

Despite those obstacles, growing numbers of young women are gathering to play cricket, basketball, and soccer. In a high-walled field an hour outside Jeddah, 31-year-old Reema recently called her soccer team together for a two-hour practice. She requires each girl to have written permission from a male guardian in order to attend the thrice-weekly sessions. Once inside the walls, with only women present, they strip down to shorts and T-shirts, throwing their Abayas in a heap. In the past the team’s members have come under criticism for their supposedly inappropriate behaviour. But as Saudis learn more about life outside the kingdom, things are changing, says Reema. “Now we know what is happening in the other world,” she says. After all, she asks, if women can compete publicly even in Iran (in baggy trousers and headscarves, to be sure), why can’t Saudi women do likewise?

Pressures and fissures are growing beneath the kingdom’s conformist veneer. Young people, emboldened by what they see on the Internet and embittered by rampant unemployment, are rebelling against parental authority and government control. Modernizers complain about the glacial pace of progress even as conservatives resist the slightest departure from the old ways. Aged and infirm royal rulers are buffeted by some of the pressure for change but seem oblivious to broader public discontent. Amid all this, women—whose subservience has been a pillar of traditional Saudi society—have become the chief proponents of change.

The fact is that women have not always been subjugated in Arabia. At least two of the Prophet Muhammad’s own wives were fiercely independent women. His first, Khadijah, was the owner of a large and successful trading company. (The Jeddah women’s center took its name from her.) The prophet was actually one of her employees before she asked him to marry her. And many years later his youngest wife, Aisha, led tribesmen in battle during the wars of succession after his death.

Today, carrying the fight to the conservatives’ home ground, independent-minded Saudi women uphold those long-ago role models and quote the Quran in support of equality. No one thinks victory will be easy. “We know the opportunities won’t come voluntarily,” says a young woman, among the first chosen by Aramco to study abroad and return to a professional job at the oil giant. (Aramco, which produces the great bulk of the kingdom’s revenue, operates as an island where sexes and religious sects can mix, unhindered by the religious police, a situation almost unheard of elsewhere in the kingdom.) “As Gandhi said, we have to make our own change,” the young woman says. “And we will.”

Karen House won a Pulitzer Prize for her coverage of the Mideast and is author of On Saudi Arabia: Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines—and Future, to be published by Knopf in September.

Source: http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2012/07/29/women-rise-up-in-saudi-arabia-the-rebellion-behind-the-veil.html

URL: https://newageislam.com/islam-women-feminism/women-rise-up-saudi-arabia/d/9609